First contact

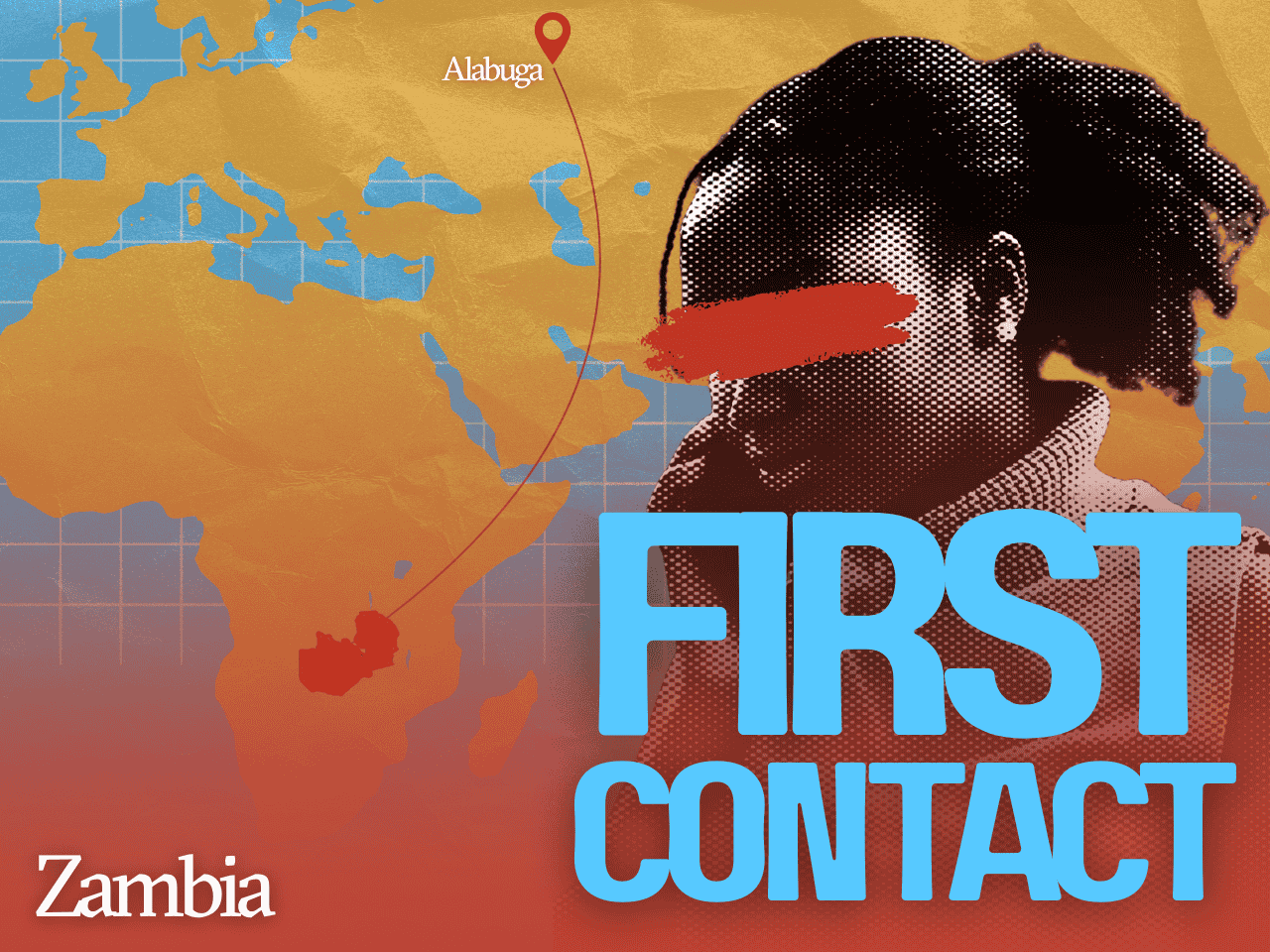

Late last year, the world was alerted to the disturbing news that Russia was recruiting hundreds of young African women, aged 18–22, to manufacture drones in a military-industrial compound called Alabuga, 1,000 kilometers east of Moscow. The reports also said that the recruits—from at least 15 African countries—were promised good salaries and skills training, but that once there, they were often trapped, facing tax deductions, dangerous working conditions, strict surveillance, and difficulties in returning home.

In the past six months, a ZAM team in seven African countries investigated the Russian recruitment exercise—and why so many young Africans grab the chance to go, sometimes even after having been warned. This Zambia chapter confirms that, once there, it is almost impossible for Alabuga recruits to freely contact home, or even to speak out publicly at all.

When we finally get to speak to a young African woman in Alabuga, the contrast with the cheerful PR shown to the Zambian public could not be greater. Brochures circulated through various media, events hosted by Russian-linked associations in the capital, and even talk shows on private TV have so far featured only smiling girls in school-like uniforms, accompanied by testimonials praising the wonderful opportunities the programme has given them. But speaking with Tabitha* casts a very different light on what the recruits are experiencing there.

It has taken us more than seven months of trying to finally make contact with an “Alabuga girl”. Getting through to a dormitory (advertised as ‘cosy’ in the supposedly ‘loving’ Alabuga environment), we find one, among seven young women of different nationalities, willing to speak to us about her experiences. From the way she speaks, she is clearly from southern Africa.

Happiness is not the impression we get

But happiness is not the impression we at MakanDay, the Lusaka-based journalism centre I work for, get from Tabitha. Even though she is apparently interested in informing us, she has repeatedly postponed our call and has nearly withdrawn altogether, answering us in the end only to voice her second thoughts. She then relents.

“Advanced materials”

Among the first things she says is that, even after close to a year, she still does not fully understand the Alabuga programme or what happens inside the compound. Among the industrial operations she says she has observed are the manufacture of automotive, construction, and what she calls “advanced materials”. “I can’t understand this company (the Alabuga Start Programme in the Special Economic Zone) and why so many people from around the world are here. Maybe they want to attract investors or something,” she says.

Asked about the military drones that are reportedly produced at her workplace, she says that she “can’t know everything that goes on here. Because this is not just one place, it is a massive piece of land with many industries.” She adds that even her identification card restricts her movements within the zone, and then asks for details of the work that she does to be withheld for fear of being identified.

Tax deductions

She has been there for the work opportunity and to save money for her family and her own future. “The salary is definitely good compared to the salaries back home,” she continues. “Of course, they didn’t mention in their adverts that during the first six months of the programme, we would face a 30 percent tax deduction from our salaries.” She says she only discovered the deduction after arriving in Russia, and she still does not know what the tax is for.

There have also been other disappointments. “Some of us here are unable to cope with the workload and the strict workplace culture,” she says, refusing to be drawn into expanding on what that means, but adding that many young people “have left the programme.” “You find people just go back. A lot have gone back.”

“People just go back”

Not convinced by much-distributed Alabuga material, – inter alia in the form of videos and comic strips – exhorting young women to learn Russian, embrace the culture, find friends, love and perhaps even a new home in Russia, Tabitha is adamant that she herself will return home after the programme next year. She dreams of living in her home country again and investing her savings there. However, she has become aware that it may be difficult to transfer the saved funds out of Russia.

“Because of sanctions,” she says, though this is likely only part of the problem: Russia has itself also introduced certain bans on foreigners trying to send money home.

When asked to introduce us to the other girls on the programme, or even her family at home, she agrees but cautions that “many are unwilling to talk” because of the “negative reports that have been written” about Alabuga in the international press. She explains that two girls in her dormitory at Alabuga are actively assisting in Russia’s recruitment drive, giving online talks to encourage more girls to sign up.

We wait for Tabitha to communicate again, to give us more contacts, but she never does.

The recruitment drive

MakanDay started its quest to discover what really goes on in Alabuga after international reports were published in October last year, showing that young African women looking for opportunities abroad were offered “fellowships” in the programme, only to end up in a manufacturing facility producing Iranian Shahed drones for use in the war against Ukraine.

Small fingers

Why Alabuga wants only very young women—applications are reserved for those between 18 and 22 years of age—has been explained with theories ranging from “typically female precision” and “small fingers” to “they are easier to dominate.” But some reports and clips openly advertised “love” and “finding a wealthy husband” at Alabuga, such as here, indicating a broader demographic goal. The Great Lakes chapter in this transnational investigation quotes a male Alabuga participant saying that “several girls got pregnant” during his stay there.

Satellite photos

Among our first efforts had been to try and picture what the Alabuga facility comprised. Contrary to the PR material that showed girls in school uniforms and talked of “study,” satellite photos did not appear to include an actual college or university. “This looks like a factory, not a college,” said a Zambian professional who has studied in Russia, when MakanDay showed her pictures of the compound. “I have never seen a college in Russia that looks like this, and I have been to four cities there. They pride themselves in education, and a structure like this as a college would be shut down.” Another former student in Russia questioned the salary figures after being shown an advert promising a 70,000 Rubles (US$860) salary. “The average Russian salary is 30,000 Rubles per month. This just sounds too good to be true.”

“I have never seen a college in Russia that looks like this”

Government silence

We asked the Zambian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Immigration Department for comment, but despite repeated requests, neither institution responded. Among other questions, MakanDay sought to know what the government understood about the programme and whether any investigation had been conducted into the purpose for which Zambians were being recruited. Instead, the government remained silent, even as recruitment drives spread widely across social media.

Other southern African governments have kept similarly quiet. According to Tabitha, the only time she had become alerted that there might be something concerning about Alabuga was when immigration officials at her departure initially delayed clearing her papers, questioning both the programme and her young age, since she was only in her early twenties at the time. Eventually, however, she was allowed to travel.

Agricultural drones

After the official Zambian requests for comment failed, MakanDay sought a response from the Russian embassy in Lusaka but received no reply there either. Immediately afterward, however, the embassy began inviting other media—perhaps considered more friendly—to visit the Alabuga Start facility.

Those who participated in these all-expenses-paid PR trips would acknowledge later that their role was largely limited to interviewing selected recruits within the compound and being shown only a few aspects of the operations. One, when asked whether they had toured any facility producing military drones, responded: “The only drone manufacturing plant we visited was one that (according to his guides) produces agricultural drones for irrigation.”

Asking the Zambia–Russia Graduates Cultural Association ZAMRUS for information also proved futile. While director Patricia Kalinga has actively promoted the programme publicly, published its material on ZAMRUS social media, and accompanied journalists on PR trips to Russia, she never responded to our questions. The Russia House in Lusaka, which has also engaged in promotional activities for Alabuga, only informed us that MakanDay’s query to the Russian embassy had been passed on to it. An official at the House promised in that message to respond to our questions but never did.

A Russia House official promised to respond but never did

Anti-human-trafficking

A last development before our deadline was a confirmation from a source within the Department of Anti-Human Trafficking that the unit had been asked to look into the Alabuga programme at the request of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Immigration Department. Talking to the source, it became clear that the request had come to the department shortly after MakanDay had approached the Ministry for comment. The source added that the department intends to interview someone from ZAMRUS, but that had not yet happened “because of a busy schedule.”

A Zambian has already died on Russia’s frontlines

While high unemployment and lack of prospects in Zambia are known to cause many of its young people to seek opportunities abroad, it remains a mystery why the Zambian authorities are not taking a more proactive role in guarding the safety and prospects of its youth at Alabuga, and more generally in Russia. This is all the more concerning because a Zambian has already died on Russia’s frontlines. 23-year-old Zambian student Lemekhani Nyirenda, together with 37-year-old Tanzanian Nemes Tarimom, had both been imprisoned in Russia on dubious drug charges, but were offered freedom in exchange for joining the Kremlin-funded Wagner Group. The deal resulted in their deaths on the Ukrainian battlefield.

A letter asking the Zambian embassy in Moscow whether it was ensuring the safety of Zambian girls at Alabuga was acknowledged but ultimately left unanswered.

*Name changed

Also see:

- Three years on: Africa’s cost in the Russia-Ukraine war

- Three Years On: Africa Pays the Price of the Russia-Ukraine War

- Alabuga. Production of death by students

See all the instalments in this Transnational Investigation here

Migrant Battalion | African governments collude with the Russian recruitment of young women into its arms industry

Cameroon | Looking for Oceanne

Great Lakes | Caught in the snow

Malawi | Sixteen unseen girls

Uganda | Trafficking station

Zimbabwe | Left behind

Kenya | Credible and licensed agents

Nigeria | A dodgy channel

Op-ed | The global threat of Russian recruitment in Africa

The Team | The team who did the Alabuga project

Call to Action

ZAM believes that knowledge should be shared globally. Only by bringing multiple perspectives on a story is it possible to make accurate and informed decisions.

And that’s why we don’t have a paywall in place on our site. But we can’t do this without your valuable financial support. Donate to ZAM today and keep our platform free for all. Donate here.