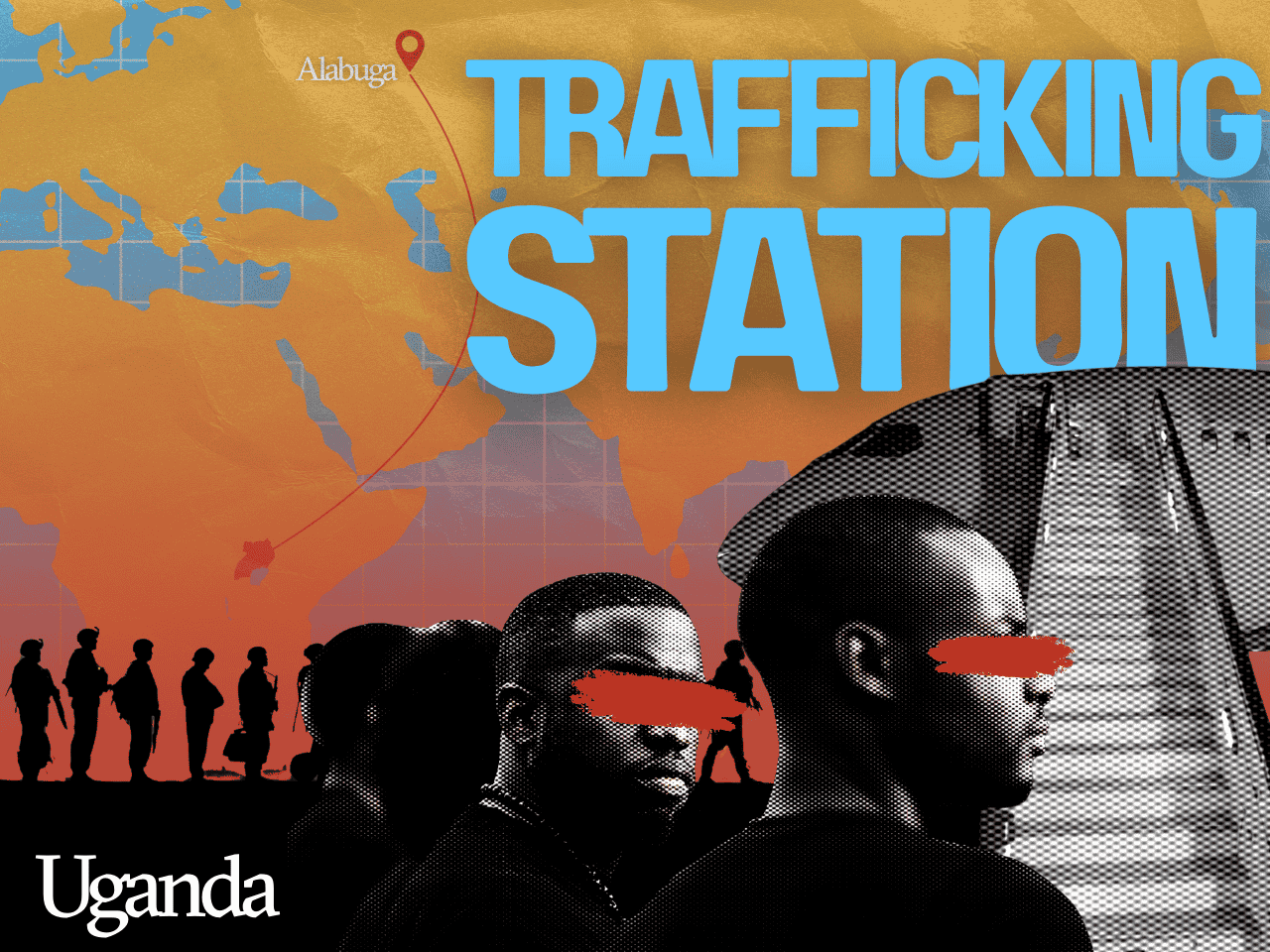

Trafficking station

Late last year, the world was alerted to the disturbing news that Russia was recruiting hundreds of young African women, aged 18–22, to manufacture drones in a military-industrial compound called Alabuga, 1,000 km east of Moscow. The reports also stated that the recruits—from at least 15 African countries—were promised good salaries and skills training, but once there, they were often trapped, facing tax deductions, dangerous working conditions, strict surveillance, and difficulties returning home.

In the past six months, a ZAM team in seven African countries has investigated the Russian recruitment exercise—and why so many young Africans take the chance to go, sometimes even after being warned. Emmanuel Mutaizibwa finds that his country is slowly turning into a trafficking station, sending young women to Russia while at the same time offering itself as a dumping ground for migrants from elsewhere.

When, on 12 August 2025, nine men were intercepted at Uganda’s Entebbe airport, ready to be flown as mercenaries to Russia, the scandal made headlines for days. The former private military contractors, who had earlier served in Iraq and Afghanistan, had been promised lucrative contracts of over US$6,250 a month by an opaque firm called Magnit, led by a Russian who is currently under arrest.

Responding to the arrests, Ugandan Defence Forces Chief General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, who is the president’s son, warned on X that, “Ugandans are absolutely forbidden from being recruited to participate in the Russia–Ukraine war. Anyone who dares will be punished severely.”

“They later came asking to take girls”

Female recruits, however, appear to be a different story. “Boys are dangerous. We are OK with them taking girls,” explains MP Edson Rugumayo when our team interviews him in his Kampala office. In the interview, Rugumayo, a member of the governing party and in charge of a ‘youth’ portfolio in parliament, tells us that there has been talk with Russia of “taking male counterparts,” but that “they later came asking to take girls, and we were okay with taking girls because boys are normally deemed to be dangerous. For a country that is at war, there are so many incentives around the country [to enlist for the military], and you would worry about that. A boy can say, if there is higher pay, let me divert and go and participate in the war.”

Bringing recruits to Russia

By the time we talk to Rugumayo, he appears to have overcome the reservations he had expressed in Uganda’s New Vision newspaper in November 2024, after reports of African young women working in the Alabuga drone factory were first published internationally. At the time, he revealed that he had already visited Alabuga in March that year “to get a feel of the place” and, while he could not “confirm or know” that any “military equipment manufacturing” was taking place, he assured New Vision that “we were careful that the project was halted until the situation normalised. Because it coincided with war. There was even a drone attack by Ukraine,” he said. “We asked that they stop until the situation normalises, then the project can continue.”

Though Rugumayo says he went to Alabuga because of “rumours” and to “check on the beneficiaries,” his visit took place eight months after Uganda’s ambassador to Moscow, Moses Kizige, had already met with Alabuga representatives and after Kizige’s December 2022 announcement that Alabuga was offering five scholarships to Uganda “and was ready to offer more”. The month of Rugumayo’s visit also coincided with the arrival of a group of African recruits, including from Uganda, at Alabuga on 22 March 2024.

The drone attack, in which several unidentified people at Alabuga were reportedly injured, took place on 2 April 2024, just after Rugumayo’s visit. The same news article in which Rugumayo made these comments featured a small interview with a Ugandan female worker at Alabuga who, speaking anonymously, complained about low wages and tough working conditions.

"Even if there were drones, it’s still work”

But Rugumayo now tells us that he has been recommending passport processing for Alabuga-destined recruits himself since. “Some of them approach my office and I assist them [to get] recommendations for passports.” Asked whether he is no longer concerned about the military-adjacent nature of the Alabuga project, Rugumayo says that, when he was there, he “never saw a factory of drones, so I don’t know. But even if there were, it is still work. So I don’t know. I have not maintained contact (…) I think that would now be at a higher level [for other authorities to take on].”

Smear campaign

Regarding those higher authorities, he explains that “there is a working relationship with the [Russian] government, and there are also discussions at the embassy level. (…) The President is also aware. If I remember correctly, it is the President who instructed the ambassador [Kizige] to chase this through so that there is a framework for Russia–Uganda labour. So I think there is a relationship that is ongoing. I think several committees are set up between the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and that of Labour, Gender, and Social Development.” He adds that these frameworks are not just for Alabuga or even Russia, because “there are many countries that are now recruiting.”

“I didn’t hear any of them complain”

Asked if he thought some of the recruits might be experiencing challenges, he says, “When I went there, I didn’t hear any of them complain,” adding that “our channels are always very open.” He puts all the negative publicity down to a “geopolitical smear campaign” in international media. “They tend to say this, but when you go there, the reality is quite different.”

Rugamayo did not respond to follow-up questions asking if he could put our team in touch with some of the Ugandan youth in Alabuga so that we could ascertain their situation for ourselves and perhaps report back to worried families. He also did not reply to the question of who had paid for his trip.

Open promotion

The recruitment for Alabuga among young women and girls in Uganda has been carried out more or less openly, with a high school among the recruiting grounds and even the former president of the Uganda National Students’ Association (UNSA), Yusuf Welunga, playing a role. “In 2022, our (then) president, Yusuf Welunga, attended a meeting with the promoters of Alabuga, but he acted as an individual,” says UNSA Executive Secretary Fred Toskin Cherukut. Cherukut added that neither he nor UNSA had an issue with this. “If our students can go to the Middle East, (youth, including students, have been going for labour and study opportunities in places such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Iraq), it is very possible for them to go [to Russia] and survive.”

The recruiter joined the secret service

Welunga is no longer at UNSA, Cherukut says. “He joined the army, and currently his phones are off. It must be the Internal Security Organisation (ISO) — the secret service that has been used against critics of the regime). He got into that programme when he was exiting UNSA.”

Labour export framework

Government sources confirmed to ZAM that there was a “labour export framework” with Russia and that 60 recruits from Uganda are now at Alabuga. However, two senior officials at the Labour Ministry, Commissioner for Employment Services Lawrence Egulu and his deputy Milton Turyasiima, appeared reluctant to give details. “I heard about this thing, but I cannot remember,” said Egulu, and Turyasiima similarly held off, saying that he had “heard about it in the background.”

At the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Permanent Secretary Vincent Bagiire denied that young Ugandan women were involved in building drones. “The information is that Alabuga is a special economic zone with various industrial activities, and that there are no Ugandans involved in drone manufacturing. The Ugandans we know of are operating in different industries.” He also said that the Ugandan embassy in Moscow is in touch with Ugandans at Alabuga.

Ugandan Ambassador to Russia Moses Kizige did not respond to questions sent to his WhatsApp asking who the recruits in Alabuga were, how they were recruited, if they were building drones, whether their working conditions were satisfactory, and if they were safe.

Increasing securocracy

Alabuga and the general military cooperation between Russia and Uganda have cast a long shadow over its Western ties. President Museveni, a long-time ally of the West in its war on terror in the conflict-scarred Horn of Africa, was previously viewed as an anchor of stability in the restive Great Lakes region. This proved a boon, as the United States provided significant development and security assistance to Uganda, with a financial war chest exceeding US$970 million per year.

Uganda has been gravitating towards Moscow

However, as Museveni’s regime has increasingly moved towards life presidency and dictatorship, opposition has been muzzled, and securocrats kidnap and torture critics—coupled with Western Europe often feebly trying to criticise these tendencies—Uganda has gradually been gravitating towards Moscow and the Far East, tightening links between its own military and intelligence apparatus and Russian counterparts.

After a first US$740 million purchase in 2012 of Russian Sukhoi fighter jets—for which reserves at the Bank of Uganda were raided—Russia has trained Ugandan Air Force pilots and engineers in both Uganda and Russia. It has also offered hundreds of bursaries to ruling party–favoured students to train at its elite universities in Moscow and Leningrad. Russian military specialists have trained Ugandan soldiers in tank operations, and Russia has donated large funds to the country’s military budgets, see here and here.

On April 6th, 2025, Museveni told the news channel Russia Today that the country has always “stood with us during our liberation struggles.” In February 2022, Museveni’s son, Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba, wrote on X that Russian President Vladimir Putin "is absolutely right" to invade Ukraine.

An ever more watchful eye

Critics of Uganda’s regime fear that the ever-closer cooperation with Russia will help local securocrats keep an ever more watchful eye on the already besieged opposition. In January 2025, Uganda rolled out a digital numberplate system provided by the Russian firm Joint Stock Company Global Security. On the Ugandan side, the system raises the spectre of increased surveillance, since the digital numberplate will be integrated with the country’s Closed Circuit Television system, the motor vehicle registration system, the e-tax system, and the National Identity database.

The country will now become a dumping ground for migrants

The spectre of an increasingly oppressive Uganda, with scant respect for humans, has also been fuelled by a recent deal with the United States’ Trump administration that offers the country as a dumping ground for the US’s unwanted immigrants. According to Foreign Affairs Permanent Secretary Vincent Bagiire, “The two parties are working out the detailed modalities on how the agreement shall be implemented.”

The irony, that on one side the West’s undesirables may be corralled here, while Ugandans may be recruited by the East—while those in the middle continue to suffer oppression and poverty—has caused concerns that the country will simply be cashing checks from both sides for operating a trafficking station. The US deal prompted Ugandan struggle veteran General Sejusa to comment: “But why is Uganda getting involved in these shameful things? Have we no pride, no ideological sensibilities, no fibre left, no shame at all?”.

Uganda’s democratic opposition is meanwhile also suffering from US President Trump’s cuts to budgets that previously helped civil society organisations. Commenting on the perilous isolation of Ugandan democrats and activists, Christopher Mbazira, Professor of Law and founding member of the Network of Public Interest Lawyers in Uganda, feared there was little chance of rescue or positive change. “There is a global realignment of governments that are relegating human rights to the background for quid pro quo deals in favour of political survival,” he said.

See all the instalments in this Transnational Investigation here

Migrant Battalion | African governments collude with the Russian recruitment of young women into its arms industry

Zambia | First contact

Cameroon | Looking for Oceanne

Great Lakes | Caught in the snow

Malawi | Sixteen unseen girls

Zimbabwe | Left behind

Kenya | Credible and licensed agents

Nigeria | A dodgy channel

Op-ed | The global threat of Russian recruitment in Africa

The Team | The team who did the Alabuga project

Call to Action

ZAM believes that knowledge should be shared globally. Only by bringing multiple perspectives on a story is it possible to make accurate and informed decisions.

And that’s why we don’t have a paywall in place on our site. But we can’t do this without your valuable financial support. Donate to ZAM today and keep our platform free for all. Donate here.