How millions meant for the sick are never spent. Health care in Nigeria is incredibly complicated. Large budgets are trapped on differ ent government levels, only accessible to those who know how to work the system. A minister wants to change that -but is he still the minister?

The Primary Healthcare Centre in Ugbamaka-Igah village in Kogi State, Nigeria, is overgrown with grasses. The labour and patient wards as well as the other rooms of the clinic are covered with dust and cobwebs and the lab is void of equipment and chemicals. Health personnel at the facility idle around. They do have some medicines for common conditions, they say, which they could dispense if a patient would show up, but for many ailments there areno drugs or treatments at all. “There are no cleaners, too,” says staff member Adejo Omale. “We do clean ourselves at times.”

The Olamaboro Local Government Area (LGA) in which this village is located, should in January 2019 (1) have received a budget equivalent to US$ 457,000. Part of this should have been used to buy medicines, sterilising equipment and other chemicals for this and the other four primary health care centres that should serve a population of 165,000 in this Nigerian region of roughly one thousand square kilometers. It should have paid nurses, technicians and cleaners to staff and maintain the five rooms and beds as well as the solar refrigerator, handwash basin, desk and wheelchair. The centres should have taken care of most common ailments that occur from time to time: from colds to simple infections and wounds to bouts of malaria and antenatal care, childbirth, vaccinations and infant care.

But the local government did not do any of these things and patients who needed antibiotics, bandages, treatment for various fevers and other primary level care needs were left to cope, and sometimes die, alone. It is estimated that yearly one million children in Nigeria die because of lack of care, including vaccinations and malaria treat- ment, at primary level.

Trapped budgets

Remarkably, as said above, this is not be- cause there is no money. The budget is trapped in a joint account that is managed by Nigeria’s Kogi State, of which the Olamoboro local government area is a part- on behalf of the region. The state has not paid the locality its due allocation in years. As a result, an adjacent rural electrification project, built at the same time as the clinic, is also not working.

The story is the same in Yaryasa and Doguwa in Kano State, and Gwer East and Edikwe, in the Apa and Gboko local gov- ernment areas in Benue state. “There are no medicines or doctors,” says Abdullahi Balarabe, a member of the local health care committee in Yaryasa that is supposed to act as liaison between villagers, their health needs, and the local centre. “The officials don’t even come here often. Today none of them came.” Bala Alasan, a 47-year-old farmer and a neighbour to the facility in Doguwa, adds that “the (health care) person who works here knocks off as early as 11:30 AM and even when you were lucky to meet him, you will still have to buy your medicines outside.”

“Outside” means the markets or the streets, where fake and expired medicines abound. Nigerian health authorities have repeatedly warned the public against buying dodgy medicines from the street because these aggravate conditions rather than cure them, but what does one do when the street is all you have?

In Gwer East, a local government staff employee in the vicinity says that staff only show up “when they like and if you ask them, they complain that they are not being paid.” An elder in the community, David Kighir Vanger, confirms that “the local gov- ernment staff came for take-over once (after the project was completed) but up till now they have not come back.”

A data search done by Nigeria’s Premium Times recently showed that none of the local government areas have received their budget allocations for years now. State governments have “pocketed or diverted over fifteen trillion Naira (N) in federal allocations – about US$ 41,7 billion – meant for local government areas in the last twelve years, depriving the nation’s third tier of government funds for desperately needed developmental projects,” the respected news site wrote in May this year.

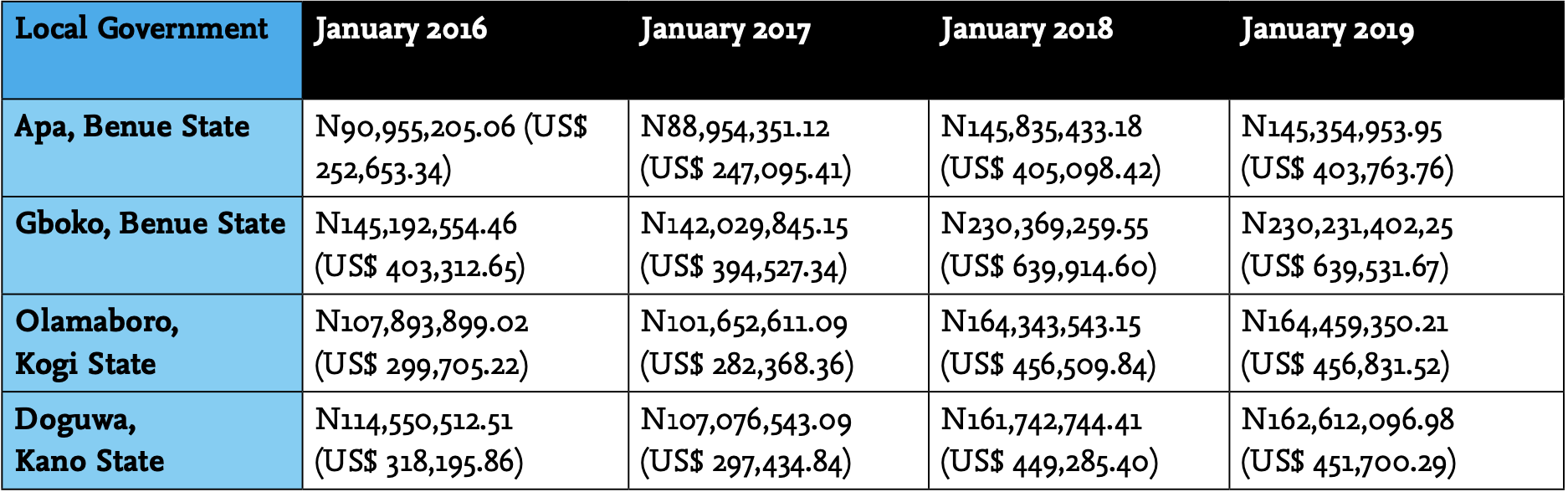

The deprivation of funding applies to the local government areas visited for this investigation as per the following table, which shows typical monthly allocations from the federal government account in January alone over a period of four years (see table 1).

The Premium Times added that this could happen “because there is no real autonomy for that level of government, and its heads are often handpicked by state governors.” This may also explain why local government heads themselves haven’t protested the ar- rangements that stopped them from doing any work for their communities.

A dysfunctional system

Former Minister of Health Isaac Adewole (2), -who called the Nigerian health care system ‘dysfunctional’ already in 2017- ad- mitted, when still in his portfolio earlier this year, that 20,000 out of 30,000 primary health care facilities in Nigeria were not working. And even of the remaining 10,000 he did not seem to be too sure, saying that “Nigerians were dying” and that “we only need 10,000 working facilities, rather than be building 30,000 ones.”(3)

Piles of rubble all over Nigeria

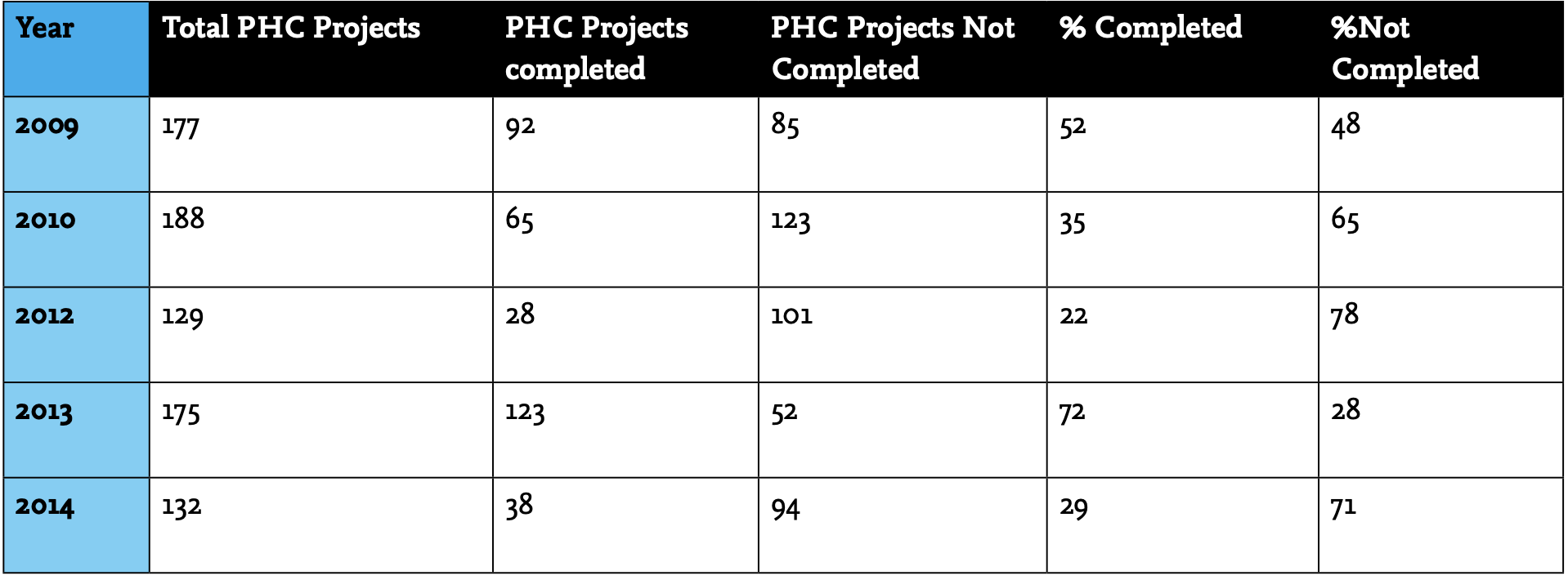

Adewole’s comment highlighted a focus on building and construction that has been a kneejerk answer to Nigerian’s health needs for a long time now. An entire programme of building clinics, started in 2009, which focuses entirely on construction and only counts completion, has been an unmitigated disaster. In most years, between 2009 and 2014 (these are the most recent figures), not even half – mostly a third – of planned buildings were completed. In 2014 alone, 132 should have been built but only 38 were completed.

It’s anybody’s guess whether the other 94 are just foundations, entire buildings with- out furniture and equipment, or heaps of bricks littered across the country.

A basic problem on the level of the building of the clinics alone, is that much of that task has been left to federal state Senators. These Senators propose budgetary allocations in order for them to ‘bring health projects to their constituents.’ When the government gives them such budgets, the Senators then -while pretending that they ‘influenced’ the projects ‘for the benefit of the people’,- often execute these in a way that opens opportunities for nepotist contracts and shoddy or negligent building. The local government area responsible for maintaining the clinic in question is then faced with a non-completed facility that is impossible to maintain in the first place, even if it had the budgets to do so.

Accessories of all kinds

At the Doguwa Primary Healthcare Centre, in Kano, for example, there is a working vaccine storage facility for routine immu- nisation, but for the rest only a hand pump for water. The floor is tattered and dusty, the bed in the antenatal room looks dirty and there is not much else. Thirty-seven million Naira, over US$ 102,000, was paid for this to a contractor called Young Stallion Nigeria Limited. But Young Stallion is, according to its own description in the company registry, not in the healthcare construction business at all. It does “trading, marketing, sales, distribution of general goods, and commission agents to (...) deal in all arti- cles (...) and things in connection with the company’s business, engineering works and construction.”

Meanwhile, the company Wawu Investment that built the clinic in Tse Vanger, Gwer East, in Benue State, is listed as able to do elec- trification works. According to the company registry it can even “install computers” and “accessories of all kinds.” However, up to today, the building has not yet been fitted with or connected to electricity; neither has any of the required equipment been installed. “This project has been a “mere strategy adopted by politicians used to win an election,” shrugs local Aondowase Yonov (25). “Or how would you explain that this small project started in 2013 but is not com- pleted and put to use up to this moment?”

Local Government Area chairman Solomon Danjuma in Edikwu, sixty-three kilometers down to the south west of Gwer East, likewise blames “politicians” for the “abandonment of the clinic project in his area.”

He says his LGA cannot do much about this because “we did not award the contract.” However, Danjuma did a “prelimi- nary investigation,” into the project, which, he says, showed that “the people who attracted (it) to the area” – in this case House of Representatives member Adams Entonu, TA – may have “collected all the monies for the project, but then failed to pay the con- tractors for its completion.” Danjuma said he discovered that the job was left undone because the contractors “left on grounds that they were not given money to complete the project. And you know some of them [lawmakers] lost elections, so they wouldn’t want to spend any further money.”

Some lawmakers lost elections so they won’t spend any more money

Lawmaker Adams Entonu did not respond to phone calls nor to a text message sent to his phone.

Poor and shoddy

In the case of the clinic in Ugbamaka-Igah in Olamoboro, locals also complain that the project was not completed as it should have been. They say that Senator Attai Aidoko (who ‘donated’ the clinic, TA) “once came with an expert to scan the environment and do the costing.” After that they had not seen the senator again. The projects had been executed by what the locals thought were ‘close associates’ of the senator, who had been handed the US$ 133,000 the building of the clinic cost. “They diverted some things and never built (the clinic) to (measure up to what) it was actually meant for”, a member of the community, who prefers to remain anonymous, says. “It was done in a poor and shoddy manner. After that nothing has happened.”

Senator Attai Aidoko’s legislative aide, Felix Jimba – who picks up the phone at the Senator’s office- says this is untrue. “He did his best (getting the) projects to his con- stituents,” says Jimba, adding that it was not Aidoko, but “the executive” (the federal government, TA) that awarded the contracts and that reports that the Senator had award- ed contracts to cronies were “nothing but smear campaigns.” He attributes all the problems to lack of maintenance by the local government area. Moreover, Jimba says, it could not be true that the projects were done in a shoddy manner because “they would have been checked before being handed over” to the LGA and that the “functionality and sustenance of the projects” after that were the “duty of the local authorities.” “The local authorities should be queried about what they are doing to sustain these projects,” he concludes.

Which means we are back to blaming the local government authorities for not maintaining the clinic, for which we have to blame the states because they don’t pay the allocations, whilst the federal government is also blaming the states for not paying their share to a national health care fund, that to make things even more complicated, also exists as a parallel structure.

It is one massive game of passing the buck

And it only gets worse. Because the LGAs, even if they would get the money to complete and run the clinics, are not fully authorised to do so.

There is yet another level.

Bureaucratic nightmare

Formally – and yes, different regulations contradict one another – the supervision of clinics in local government areas is a responsibility of state agencies called primary health care development agencies (PHCDA’s). So the state governments, under which the PHCDA’s fall, do carry responsi- bility for the clinics after all. And since they also hold the budgets for primary health care, the solution should be simple: it is to manage the finances and the operations of the clinics on state level.

But not so in Nigeria, where state senators use clinics as a game to win elections, then point for their staffing and maintenance needs to local government areas, then blame the local government areas for not doing their duties whilst also not paying them needed budgets, then justifying their non-payment of the budgets because they need to manage their state level health care agencies, the PHCDA’s. It is the stuff of bureaucratic nightmares.

Neither state Senator Aidoko, nor his legal aide Felix Jimba -who had said the local government was supposed to maintain local clinics – answer subsequent phone calls meant to ask them about the responsibilities of his state government with regard to the clinic that, in 2014, Aidoko ‘donated’ to his constituents.

The Health Ministry wants to streamline

During his term that ended this year in June, recent Health Minister Isaac Adewole (4) has made efforts to streamline the ‘dysfunctional’ system by decreeing that central budgets should be made available only to the provincial Primary Health Care Development Agencies and that these should shoulder all responsibilities with regard to supervising, supplying, maintaining and staffing local clinics from now on. (see box). This would be a positive structural reform, in line with Adewole’s passion for -as it says on his Twitter bio- “achieving Universal Health Coverage by fixing the PHC system” in his country. However, in Nigeria’s turbulent political landscape after recent elections it remains unclear whether Adewole will return as Health Minister for a new term.

*

The most recent Minister of Health in Nigeria, Isaac Adewole, directed harsh words about the non-working clinics in May last year mainly to the Nigerian states which, he said, are not complying with their duties in terms of the Primary Health Care Development Agencies (PHCDA’s) and the allocations that should enable these structures to super- vise the clinics and their functioning. He decreed that primary health care fund- ing would henceforth be made available directly to the PHCDA’s and that these would now oversee both the building, equipping, medicines distributions, staff- ing and other needs of the centres.

This was welcomed throughout the structures of the PHCDAs. The Executive Director of the Kogi State PHCDA, Dr Abubakar Yakubu, said in an interview that a lot has already been done to “address the issues of manpower gaps and inadequate drug supplies in (the clinics.)” Giving examples, he mentioned that a census of personnel and facility needs had been done in the state and that “the state governor recently signed a bill to bring all primary health care in the state under one roof to ensure proper coordination and efficient service delivery to the people.”

Yakubu also said that about two weeks ago, medicines had been supplied to over three hundred primary health care centres in the state. Improvements were reported also in Kano State where, according to PHCDA executive official, Dr Nasir Mahmoud, over three thousand primary health care facilities “are now under (the overall agency’s) control” and that “renovation of many identified dilapidated centres” had already begun. Under the new arrangement, PHCDA’s in the states would also take over maintenance and the supply of medicines and other essentials in cases where state Senators would attract new health care projects to the regions. This would relieve local councils, who could then use funds they receive from the central government plus their internally generated revenues for other purposes. Locals in Ugbamaka-Igah village continue to hope in that respect for some attention to their electricity supply, which is needed for the clinic as well as their households.

1. See table 1

2. A new minister of health still needs to be appointed after recent elections in Nigeria.

3. https://leadership.ng/2019/05/22/20000-health-centres-abandoned-minister/

4. Data over 2011 are missing from the Primary Health Care programme report.

5. At the time of writing this, government formation was ongoing in Nigeria after elections and it was uncertain if Health Minister Adewole would return to his post.

6. The regional case studies for this report were select ed as follows: Kogi State, because author Theophilus Abbah is from there (which helped access important sources in the area). The other clinic locations in Benue and Kano States were randomly selected.