A transnational investigation by the African Investigative Publishing Collective

“Lack of clear authority” left the time bomb ticking since the 1950s

BENUE STATE, NIGERIA, February 2017

70-year-old Chief Godwin Onah, the paramount ruler of Agatu in Benue State, talks of the destruction of both his palace and his community. “I’ve been homeless for three years now. I live with friends.” Nostalgically recalling the olden days when “my father and nomadic Fulani herdsmen exchanged mangoes in the farms,” Chief Onah describes how the lush and fertile land in Agatu was good for cattle grazing, while the dungs from the cattle helped to fertilize the land for good crop yield.

There had been occasional skirmishes in the olden days too. But they had started to increase in the new millennium. And when in January 2014 the area was invaded, the palace destroyed and all the buildings -churches, schools, hospitals, markets, houses- were burnt down in a midnight invasion by AK-47 rifle wielding killer-herdsmen, deaths had started, and continue to occur, in dozens. Different accounts mention the number of destroyed Agatu communities since then as between 22 and 60, though the degrees of damages done to property, farms and human lives differ from one community to another. “We labour without knowing when next our harvests will be destroyed,” says Chief Onah.

BENUE STATE, NIGERIA, April 2017

Nearby Gwer’s paramount Chief Daniel Abomtse, whose farm was also razed, echoes Chief Onah’s despair. “My people can no longer go to their farms because of gun-wielding Fulani who attack and kill them. Many of my villages have been destroyed, but we are yet to see any concrete security steps taken by government.” He says the only visible government action with regard to the tragedies of Agatu and Gwer has been a fact-finding mission to his area, in March 2016, during which the country’s Police Inspector-General Solomon Arase, told locals that “we have enough security officers to end the ongoing crisis.’ Arase had gone on to admonish the public that farmers and herders should simply “learn to cohabit with one another as a nation for the peace and progress of our people.” “(That visit) did not show any seriousness,” Chief Abomtse shrugs.

Foreigners

Benue state coordinator of the Myetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association (MACBAN), Garus Gololo, has said publicly that it is not Nigerian, but “foreign” Fulani herdsmen who are the problem. “They come from Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Chad through forest routes with their weapons. They destroy communities, then disappear.” His words are echoed by Fulani leader Ardo Boderi Adamu, the deputy chairman of the recently instituted Benue Agatu-Fulani Reconciliation and Peace Committee, who takes issue with the accusations against his people. He says the Fulani just want to live in peace with the farming communities. "Like we have done for 60 years without any problem.”

Denying responsibility for the destruction and the massacres in the villages, Bodero claims that “young men from Agatu” started the conflict in 2014 by “killing one of the Fulani leaders and taking as many as 800 cows.” He also says that “Agatu youths killed six of our children and many cows since then. They now guard the Benue river, stopping us from passing with our cattle. That is against the (Nigerian) Constitution, which guarantees freedom of movement in the country.” Boderi also says he believes that the killers with the AK-47 rifles who razed Agatu and Gwer were “foreigners.”

But Chief Abomtse has lost patience with that excuse. “The Makurdi air base is nearby here. The army could just use surveillance planes. Is Nigeria saying it allows foreigners to come and destroy Nigerian farms? Who is fooling who?” The Chief also doesn’t have time for Boderi’s appeal to the Constitution. “The freedom of movement is for people, not for cattle who destroy crops.”

Nevertheless, a protocol established be the Western African association of states ECOWAS, does guarantee nomadic pastoralist farming rights. It is that ECOWAS protocol that nomadic herdsmen chiefs and cattle owners appeal to, and that governments in ECOWAS, to date, have not dealt with. All the while, as pastures get scarcer, the herdsman groups need to move further and further, encroaching on farms and fighting farmers as they roam.

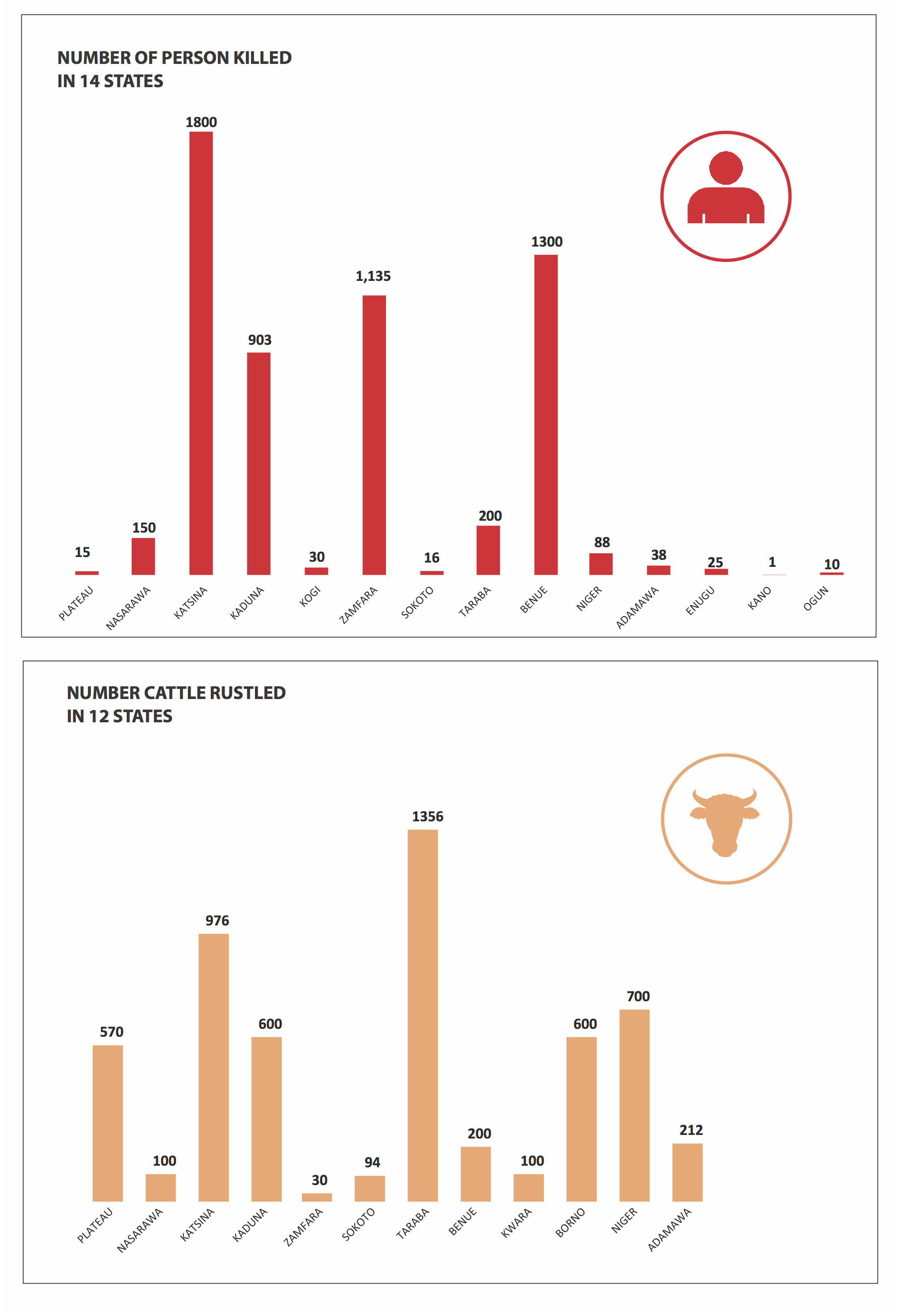

After the first 300 deaths in Agatu in 2014, at least another thousand people have died in the violence in Benue State in the past three years. The blood of thousands murdered has also soaked the ground in Kaduna (1,800), Nasarawa (150); Taraba (200), Zamfara (1,135); Adamawa (38); Niger (88); Katsina (188); Sokoto (18); Kogi (30); Enugu (25); and Ogun (10). Totalling close to 5000, these are only the cases that were reported in newspapers. The full death toll is likely higher since often, bloody incidents in remote communities do not even reach the media.

The World Bank said it was counterproductive

The crisis had been foreseen as early as the1950s, when the need to establish new grazing land areas for Fulani in the North was recognized by the British colonial government. However, plans for this were dropped as a result of a report by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (now the World Bank) in 1954, that decreed that “unrestricted grazing (…) as used by pastoralists” was “counterproductive and (amounted to) inefficient resource depletion.”

Ten years later, after independence, the postcolonial government had again made efforts to address the question, earmarking grazing reserves of in total 6.4 million hectares under the Northern Nigerian Grazing Reserve Act of 1965. But what were designed to be no less than 417 grazing reserves came to nought again: mainly because, meanwhile, oil had been discovered. And with dollars flooding in for the ruling elite, no one with power seemed to be interested in what was happening to the rural populations anymore. Those who were interested in agriculture, like the World Bank and Western donor countries supported agribusiness, irrigation and land tenure projects in Nigeria, apparently also without a thought for grazing lands.

MACBAN researchers Mohammed-Baba and Bello Tukur who have advised several bodies on the issue of pastoralists’ needs, say that the neglected grazing reserves plan from then on suffered a continuous “lack of clear authority” with regard to which government structure should look after the reserves and also a “lack of amenities such as markets, schools, veterinary and human medical facilities.” They also note “failure to actually issue land titles for pastoralists,” and “machinations of and/or collusion among political and security officials (and) traditional authorities.” As a result, out of 417 earmarked territories only twenty are suitable for grazing today. The rest has either desertified or been encroached upon by expanding urban areas or farmlands.

Committees and committees

Nigerian authorities in the new millennium have stated they are aware that oil exploitation, urbanisation, land grabbing by some in the elite, coupled with the fact that the population keeps growing -as does the percentage of unemployed youth, who also increasingly return to family villages-, were a growing problem. In 2009, the Nigerian government, through a spokesman in the agriculture ministry, again announced the establishment of grazing reserves and cattle routes, as well as a committee. In 2014, then minister of agriculture Akinwumi Adesina, saying that “we must do something very quickly because the conflicts are getting more violent,” proposed once again that there should be grazing lands where nomadic herders should settle: “We should stop moving cattle and start moving beef.” Adesina announced a new committee which he was to chair himself. Yet another committee, established in 2016, is still to produce a report.

The Fulani are not registered

One reason for the lack of action is the fact that to date, there is no answer to the question who will be accountable, financially or otherwise, for the management and upkeep of grazing reserves and cattle ranches. Livestock is big business, and the Nigerian government would like serious investors to come to the table. But the cattle owners in West Africa are the Fulani, who are not established in company registries and board rooms, and therefore difficult to invite.

This background perhaps explains why the Governor of Benue State, Samuel Ortom, during a visit in March 2017 to a camp for the internally displaced in Makurdi, could not think of anything else than to announce that he had now ‘ordered’ the herdsmen to leave his state because “they are not friendly to my people.” Or why his deputy, Benson Abounu, emotionally appealed to the nomads that it was really not ‘modern’ to “move cattle from one place to another anymore,” exhorting them to “stop being ‘resistant to change.’ It is expected that a new law passed by Ekiti State that forbids “open grazing” and “movement of cattle from one place to another at night” will have just as little effect.

The Emir of Dansadau tries hard

In the face of government inactivity, communities in Zamfara State have been trying to make peace with cattle herders themselves, even after these appropriated a large farming area in Dansadau and forbade farmers to even tend to their lands. The farmers, by all accounts, had been fully entitled to defend themselves against the herdsmen. After all they had morphed into bandits, rustling cattle from sedentary farmers, killing men, raping women and assembling thousands of cows at their camp deep in Boruwai forest, where even -in the words of one farmer- “the military feared to tread.”

Nevertheless, a historical peace meeting took place in January this year on the initiative of the Emir of Kaura Namoda, Alhaji Ahmad Muhammad Asha, who had used his traditional authority to invite both farmer vigilantes and armed cattle rustlers to meet face-to-face for the first time at his palace. (The happily smiling Emir had been cautious enough to also invite the cream of the state’s military personnel, led by the commanding officer of the Zamfara 223 Light Tank Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Abdullahi Adamu Aliyu. the Divisional Police Officer of the Kaura Namoda LGA, as well as a government delegation, but they were never called upon to intervene as all present kept their calm.)

It was almost unbelievable that farmers were ready to sit down with the bandits after the horrors inflicted upon the former by the latter. Interviewed shortly before the meeting in the nearby village of Wanke, where the displaced people now lived as refugees, farmer Yusuf Galadima had reported that he could not even visit Dansadau anymore. "If you go there, the bandits would surround you and demand money or your motorbike. Sometimes they would just open fire on you and then ride off." Galadima had been about to harvest his usual 200 bags of sorghum when the rustlers had arrived late last year. “They did not even talk to me. They herded their cows into the farm to feed and destroyed most of it. I was only able to harvest 33 bags and have not been back for a long time.” Audu, another farmer, had pleaded with the bandits to let us give the cattle the chaff, but they insisted on feeding on the grain. We had to leave everything for them for fear of our dear lives.”

The bandits had also attacked sedentary cattle farmers in the area. Aliyu Audu from Mashema village in Bugudu said he alone had lost 200 cows to an attack by the bandits in November 2016. “The bandits entered the village, shooting into the air and attacking from house to house that night. They made straight for the cows and herded them away.” He had gone out and chased them, but “they noticed that I was after them and one barked at me to stay away.” Audu had pleaded with them but then “one of them fired shots in my direction and dashed into the forest, thinking they had killed me.” The bullets had pierced his neck but not hit anything vital and he survived, -unlike twenty others, who, say the people in Wanke, died that night.

But at the meeting at the Emir’s palace, rustler Chief Alhaji Ardo, invites the farmer vigilante leaders to come forward and shake his hand. And then the vigilante leaders do stand up and, under thunderous ovation from the communities and the bandit group, trudge through the crowd to do exactly that.

"We have decided to drop our arms to give peace a chance,” Alhaji Ardo continues. "We do this (..) because all our faces are wearing frustration and gloomy looks. We have weakened the rural economy. Farming, herding and trading have become nightmares. We have stopped farmers from going to their farms. We have taken lives and destroyed properties.” But both sides are responsible, he adds. “You, our brothers, local vigilantes, have killed our kinsmen and we have also taken the lives of yours. We can't continue like that. Life has become brutish, nasty and short.”

A temporary truce

Several bandits then explain that they had been forced into rustling after their cows had been stolen and communities destroyed. They also despair of the current situation they say, where farmer vigilante groups stop them from coming to certain towns and markets. Truce deals are now made. The bandits will allow the farmers to come back to the Gusami rural market in the Birnin Magaji local government area, which they had appropriated and where they used to parade, brandishing all sorts of rifles. In turn, vigilante leader Kabir Musa Kurya, agrees that the bandits will henceforth be allowed to visit the Dogon Kade market, which was previously inaccessible to them. After this peace deal between bandits and vigilantes in Zamfara State, there have been pockets of attacks in rural areas, but it has not escalated to match the mayhem of 2016.

Or rather, not yet. It remains to be seen how sustainable this deal is, bearing in mind that it does not include the return of cows rustled, the payment of compensation, or any permanent solution. In Zamfara, a desperate people were asked to forget about all that, whilst remaining in a reality of continuing competition for land under an incapacitated government.