In the early 2000’s, two serial killers roamed Swaziland. Only one of them was human.

In mid-March of 2001, twenty-six-year-old Samantha Kgasi-Ngobese disappeared. She had planned to travel to Mbabane, the capital of Swaziland, to apply for a job at the High Court. Samantha had a law degree from the University of Swaziland and was hoping to use it.

But at the bus stop in Manzini she met a man who promised her a job at a chemical company. It would pay 4,000 emalangeni (a bit less than US$ 500) per month, a very good salary in Swaziland. Excited, she ran back home to change. When I spoke to Mable Kgasi, Samantha’s mother, in 2011, she remembered how hopeful her daughter had been when she came home. “‘Mommy, mommy! I’ve got a job,’” Mable remembered her saying. “‘There’s a man that’s offered me a job.’”

Samantha never returned home after that.

Around the same time, a man named Simon Motsa reported that his wife, Fikile, a thirty-seven-year-old pre-school teacher, and his one-year-old daughter, Lindokuhle, had gone missing. Simon had last seen his wife and daughter on the night of March 10, when he and Fikile had an argument. The couple did not live together during the workweek, and she had left Simon late to head back to the home of her in-laws. Motsa was concerned because Fikile and Lindokuhle would have to walk in the dark. There were few streetlights in Swaziland back then.

Days later, he found out that his wife never arrived. He reported her missing to the police in Matsapha. He called the major hospitals. He even visited ‘diviners’: traditional healers who could perhaps help by communicating with the spirits of the ancestors. But they “could not see her in their mirrors.” This led Simon to think that his wife was dead.

Eagle’s nest

Then on April 2, 2001, in nearby Eagle’s Nest farm in the one-market town of Malkerns, a worker came upon the decomposing bodies of two women and a baby girl. The bodies had been in the bush about three weeks, and one of the child’s legs was missing. Simon Motsa was able to identify two of these bodies as his wife and child. Fikile’s hands had been tied behind her back and she had deep cut wounds on her head and neck. He recognized little Lindokuhle by her clothes. The third body was not positively identified.

A few days later, a skull was found in a plastic KFC bag in the same area. On April 10, six more skeletons and a decomposing body, all within a short distance. The police began warning people to stay in their homes at night.

These bodies were all found in or near the huge man-made Usutu Forest, which spreads over more than 160,000 acres. These woodlands of pine and eucalyptus, cut for pulp and timber, cover nearly four percent of Swaziland’s landscape. For miles, the long-trunked trees are set apart from one another at perfectly matching heights, like armies of clones.

Front pages

By April 2001, when the body count reached eleven dead women and children, two of the nation’s top cops, Superintendent Jomo Mavuso and Senior Superintendent Khethokwakhe Ndlangamandla—with a combined fifty-three years of experience on the force—were assigned to head the investigation. On April 12, they brought more than 200 police officers and soldiers to comb the Eagle’s Nest area. An additional thirteen sets of remains were discovered, some just loose bones, but several more had flesh still remaining.

With news of the bodies spreading to all corners of the country, reports of missing women began pouring into police stations and making the front pages of the dailies. Sizakele Letsiwe Magagula, twenty, of Emalangeni, under Chief Hhobohbobo, had disappeared weeks earlier. Siphiwe Goodness Ginindza, seventeen, of Feni, under Chief Myengwa, hadn’t been seen since September 2000. Nelsiwe Ndzinisa, twenty-five, of Madlenya, under Chief Madlenya, had vanished in December 1999. The list went on and on.

Most of the women were last seen in, or known to have been traveling to, Malkerns or Manzini, towns where job seekers might head. Manzini, along with its next-door neighbor Matsapha, is the centre of industry in the country, and comes closer than any other city to a truly urban atmosphere. Malkerns, by contrast, just a few miles down the road, is situated in a picturesque agricultural valley of maize and pineapple fields, lined by unsullied mountain ranges where Swazi royalty are buried.

Several missing women had last been seen with a man who promised them work

Police attempted to track down those who had last been seen with the victims. In several cases, missing women had last been seen with a man who had promised them work at a garage or a packing plant, or even at a police station.

Demons of the devil

The whole of Swaziland joined in the search. “There was this hype,” the husband of one victim told me. “Religious people were praying, women were marching, saying ‘the killer must be found.’” As part of a prayer service at the soccer stadium during the Easter festival, the Indlovukazi, the king’s mother and co-ruler of Swaziland, called, as one newspaper writer put it, “upon Christians to pray for the country, as it was apparent that the demons of the devil have taken its toll.”

People turned to the ancestors. Like those who believe Jesus is present in every moment, Swazis—even most Christian Swazis, in this country where traditional and imported beliefs co-exist—see the ancestors as guardians, watching them, speaking to them. A diviner or healer, also called sangoma, is thought to be able to speak with the ancestors better than the average person.

Zionist Christian prophet Simanga Mthalane vowed to assemble a team of prophets that, using divine powers, would find those responsible and bring them to the authorities. “This is war,” he said. Remarkably, Mthalane requested that the police provide his team with protection in case his investigation “led to people in power.”

David Thabo Simelane was recognized at a supermarket by the husband of a missing woman and arrested on April 25 in Nhlangano. He confessed to the crimes then and there. “Calm and collected,” one of the original arresting officers told me, “that man said it was him.”

Calm and collected, the man said that it was him

Constable Vusi Dlamini, at the time a low-ranking police officer not assigned to the case, had lost his wife, Sindi, to David Simelane. When I met Dlamini in 2011, he told me about his agony. “As a working policeman, I was using a firearm,” he said. “Many times—more than ten times—I thought ‘in three seconds this misery can just…’” It was during that conversation that I saw, for the first and last time, a Swazi man crying.

Like Simon Motsa, Dlamini had consulted a 'diviner' to help find his missing wife. But unlike Simon Motsa, he did actually “see” Sindi in the curtain the diviner hung up for him. Though this was only after staring at the curtain for a full thirty minutes, as the diviner prompted him to do, Dlamini was desperate for that to mean that she was still alive. “I never believed in that. I’d rather believe in God,” Dlamini said with misty eyes, as if he was again seeing his wife. “But that day I believed.” Sadly, it wasn’t the truth. Sindi had died three weeks before then.

But as much as Vusi Dlamini had been tempted to believe in the projection offered by the diviner, he could, when informed of the identity of the perpetrator, not believe that Sindi would ever have voluntarily gone anywhere alone with David Simelane.

A broad forehead and bloodshot eyes

David Simelane was forty-three years old when arrested and had not finished high school. He did not own a car. He lived in a single room with one lightbulb and no electrical outlets or running water. He had a police record for assault and robbery. Nor was he particularly attractive. As one Swazi writer put it, “when David Simelane stepped out of a white minibus, handcuffed to a police officer, numerous lower-lips fell to the ground in disappointment. He was dark in complexion, with a broad forehead, bloodshot eyes, an apology for a nose, and a mouth that must have been carved with a pencil knife. David was anything but handsome. He was dressed in blue jeans and a navy-blue T-shirt with a red stripe and a brown windbreaker—a rather unsavoury colour combination.” Swazis were mystified. A woman would have to have been profoundly desperate to believe in the “job offers” made by such a man.

The official story during the trial was that all victims had followed David Simelane voluntarily into a remote place in the mountains under the impression that they were going to find employment. But even the judge, the Honourable Jacobus Annandale, found that difficult to believe. “Even the most trusting, the most eager person would have had to suspect something,” he would write in his judgment.

Most of the women Simelane killed were from rural areas, part of the forgotten majority of Swazi society, largely poor and uneducated. They could, perhaps, have been desperate enough to believe that Simelane had a job for them. But Sindi Ntiwane, Vusi Dlamini’s wife, was relatively well-off. Her father had lived all around the world and had written, with Sindi’s help, textbooks for the Swazi curriculum. Her family was successful and intellectual.

Sindi Ntiwane had been relatively well-off

Potential business partners

Sindi Ntiwane had not been looking for a job, but for an investor to help open a clothing shop like the one her parents owned, which would make uniforms and badges for schools. The night before she disappeared, Sindi said she had found potential partners to help her kick off the business and that she would be meeting them the next day.

Vusi and Sindi had cell phones, uncommon in Swaziland back then. At around 8 AM, she called and told him she was heading to an area called Bhunya. Dlamini asked himself only later why she was heading to this mill town. There were few schools in Bhunya. It didn’t seem an appropriate place for a shop that sold student uniforms.

In Simelane’s written confession he admits to strangling Sindi “to death with my hands.” A skeleton and clothes that belonged to Sindi Ntiwane were found at Nkonyeni Farm in Sidvokodvo. As her husband and the last person who was known to have seen her alive, Vusi Dlamini was brought in during the trial to identify her belongings, including a quartz watch that Sindi loved. He remembered the day when she came home crying because the watch had gotten a small crack. That same small crack helped prove that Sindi was in fact one of the deceased. The police had found the watch at David Simelane’s flat.

A 2001 video from the police station shows Vusi Dlamini, only twenty-seven years old at the time, sitting no more than a few feet from David Simelane, identifying Sindi’s dress and T-shirt. Vusi is stiff in the video, his lips tight, the man who murdered his wife within arm’s reach. “They made sure that I was not armed,” he told me. None of the officers nearby were carrying weapons either, in case Dlamini tried to steal one and attack Simelane. He told me he might have. “I would have killed him. And I didn’t mind if I got killed.”

Muti murder

Neither the murderer nor Sindi’s husband died that day. But many people connected to the trial of David Simelane were dying then, and continued to die during the five years of the trial, which ended in 2011.

Five of the eleven original police investigators died, including both lead detectives. Two of Simelane’s young girlfriends died before they could act as witnesses. The magistrate who took Simelane’s second confession passed away in 2007 at age forty. His wife died three months later. Reporters, relatives, and, most importantly, witnesses—dozens of them died during the trial. So many of the people involved with the case died between the time he was arrested and the end of his trial that it seemed Simelane was somehow taking out those who could speak against him.

Which is precisely what the nation believed.

People thought that David Simelane had the support of a higher power—and not a benign one. One woman I spoke with before the trial ended told me, “When he gets out he’s going to kill everybody….This is Swaziland; he’s going to come back.” A relative of a prominent member of the court who died during the investigation told me years later: “I’m scared to talk. All the people that were in touch with this matter are dead.” And a man who lived in the Malkerns area said: “The people here may know something, but they won’t say. They don’t want to get involved. Even if they saw something, they won’t tell you.” A policeman who became a witness in court after his boss died explained to me that people had started to blame witchcraft. They thought that David Simelane was using muti to destroy his case.

“Even if people saw something, they won’t tell you”

In its most basic meaning, muti is simply medicine. It refers to the herbs and actions used by diviners and traditional healers to treat a variety of psychological and physical ailments. Some of these medicines help ease pain; some stop diarrhoea; some disinfect. But the police officer was referring to another type of muti: medicine wielded by witch doctors that, rather than heal, can hurt or kill from afar. “But I don’t believe in witchcraft,” the policeman told me.

Simon Motsa’s little girl had been found with only one leg

In many ways the people who thought that witchcraft played a role in the Simelane case were wrong. David Simelane wasn’t using evil powers to take out witnesses during the lengthy trial. But the talk of muti was far from paranoia. Simelane himself had admitted on camera, in secret videotapes I found ten years later, that his victims had been killed for their body parts to be used by witch doctors as ingredients for muti: a strong kind of muti that might protect you from rivals, enemies, and even death. In the video, Simelane claims to be a lowly assassin, contracted to kill women and children to obtain body parts for more powerful people. Several of the skeletons of Simelane’s victims were missing parts when they were found, including Simon Motsa’s little girl, whose body had been found with only one leg.

Extreme measures

In 2001, AIDS was ravaging the country. There wasn’t a single family that hadn’t lost friends, parents, children, a sister, or brother. AIDS was the killer that had taken so many witnesses in David Simelane’s trial. But it wasn’t just people connected to the Simelane case who died. It was everybody. Swaziland was sick and its people, rich and poor, were dying. If ever there was a time and place that could call for extreme measures such as strong muti, this was it.

Senior investigators Jomo Mavuso and Khethokwakhe Ndlangamandla appear certain, in a video taken on June 6, 2001—nearly a month after Simelane had given his written confessions—that there was more to his deeds than just ‘revenge’ against women. In the written confessions, Simelane claimed to have killed women due to a false rape charge that landed him in jail for many years. But the video shows the policemen telling Simelane, in very calm siSwati: “You were used. You were getting paid for killing these people. There is someone or someones who were using you, paying you.” (…) “There was a witch doctor behind this. There was a witch doctor who made promises to [those who would get] the body parts.”

During the trial, these questions were buried and the motive of muti murder was no longer explored. But virtually all the people I spoke to said they thought that the official version of Simelane’s motive did not hold water. “There are not enough questions asked,” Samantha Kgasi-Ngobese’s sister, Charmaine, told me. “The people he killed didn’t have much money. We never heard of him housebreaking. Where was he getting his money from?” “He brought them to some syndicate,” said Samantha’s mother, Mable. “He was bringing them, getting paid, and throwing them away.”

Influential people

On June 12, 2001, seven weeks after his arrest, a month after the confession in which he listed his victims, and six days after the police put the muti murder motive to him, Simelane gave three additional names. All three were famous men in Swaziland: Peace Mfana ‘Boy’ Motsa, a wealthy businessman who died in May 2014; Majahebutimba Dlamini, a member of Parliament who died in 2003; and a third man, still alive, a former member of Parliament. These were the people, Simelane said on camera, who hired him to kill.

According to the late social anthropologist Harriet Ngubane, it is believed that those who turn to ritual murder are not everyday people. They need to have money to hire killers and power to avoid being detected. In 2001, all three of the men named by Simelane were influential people in Swaziland, often in the newspaper headlines for their business dealings and work in government. Each of them had since been involved in multimillion-dollar personal or government investments. In the video, David Simelane rocks back and forth in his chair and stares at the ceiling as he tells the cops how, toward the end of the Swazi winter of 1999, he had run into Boy Motsa. Motsa had said he had a job for him and that he was looking for someone to kill people and take their body parts.

Simelane would be paid about 370 US$ per month and given taxis and a minibus

Simelane had accepted and that evening, he met Motsa’s two partners, both of whom worked in Parliament at the time. They agreed that Simelane would be paid E3,000 (about $370 US) a month and that he would also be given two communal taxis and a Sprinter MiniBus. They set the routes he would take to find victims, chose a meeting place in Mahlanya—the area that one of the men, Majahebutimba Dlamini, represented in Parliament—and appointed Motsa as point man in case something went wrong. “Once we have reached a fifty target figure, none of us will be lacking money,” Simelane said he was told. He also told the police that his employers had personally participated in seven of the murders, and that they had used a Nissan one-ton pickup belonging to one of the partners to transport the victims to secluded places.

But if Simelane was working with these powerful people, he never once mentioned them in court, and nor did the police. The original two investigating officers, who had interrogated him about a possible muti murder scenario, were dead. Judge Annandale would later rule that no connection had been found between the crimes and any other person besides Simelane.

Hidden details

In the official account of the murder of Rose Nunn and her child Nothando, as narrated in Annandale’s judgment, Simelane states that he “strangled her to death, with her child, with my own hands.” But what was not in the judgment, nor ever presented in court, were the additional details that Simelane gave in the video from June 12, 2001. He said then that he, Nunn, and the baby had met the partners at Mahlanya and that they had all driven to Usutu Forest. That the partners had held the woman down while he “pierced her in the neck.” That they had cut out Rose Nunn’s liver and heart, cut off parts of her thighs, and killed and took brain issue from the child. That they had rolled the parts up in a plastic bag and got rid of the clothes so it would be more difficult to identify the victims.

I spoke with Boy Motsa over the phone a few months before he died. When I asked if the police had ever spoken with him about the David Simelane murders, he laughed and said that his only connection was the rumours brought on by a public offer he made to purchase coffins for the victims.

I’ve also spoken to the only remaining man named by Simelane that is still alive, the former member of Parliament: When I first asked him over email if he’d ever been questioned about the murders, his response came in thirteen minutes and consisted of an expression of complete surprise. A letter sent to me in June 2014 by a representative of the National Commissioner of Police stated: “We can with absolute certainty say that the accused acted alone, and this version remains uncontroverted.” The police did not respond to any specific questions about the partners Simelane named.

“The case will be over, but it will never be over over,” Charmaine Kgasi-Munro told me. “Because we know there’s more to it, and there’s nothing we can do.”

In the hands of the king

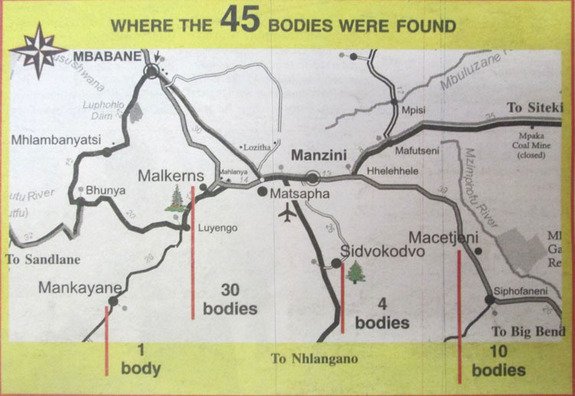

Annandale made his judgment on March 23, 2011, finding Simelane guilty on twenty-eight counts of murder. About forty-five bodies had been found in all; thirty-four were charged to Simelane and twenty-eight were used to convict him. The Swazi Observer, a popular daily, printed the entire 40,000-word judgment the next day, headlining the death sentence. The judge, who usually found ways to avoid putting even convicted murderers to death, had found no mitigation in the case of David Simelane.

King Mswati III of Swaziland, however, has not allowed a hanging since his coronation in 1986. All prisoners condemned to death row either sit there still or have had their sentences commuted. To this day, David Simelane’s life remains in the hands of the king.

Shaun Raviv is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta, Georgia. He lived in Swaziland for two years.

Article photo: Judge Annandale (left), Khethokwakhe Ndlangamandla, and Mumcy Dlamini (the chief prosecutor), with David Simelane in the background.

This is a summarised and edited version of a (highly recommended) full long-read, first published on ‘The Big Round Table’. Read it HERE.