Hungry children and white saviours are still very much present in campaigns by Dutch aid organizations. But also, many of the new aid campaign genres are problematic, observe media scholars Emiel Martens and Wouter Oomen. Every year they present the Fly in the Eye Award for the worst campaign on behalf of IDleaks, a Dutch non-profit organization committed to better humanitarian communication. What is going wrong, and how can it be done better?

This week, Save the Children UK, the oldest international NGO in the world, released a statement of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. The NGO stated that it would check its own campaigns to see whether they contain racial stereotypes that 'strips agency and dignity from children' in vulnerable situations. In addition, they argued that they will 'remove white saviorism' from their communications' and ensure that ‘the lived experience of Black families and families of color in poverty is at heart' of their communications.

The fact that Save the Children, of all organisations, comes forward with this message is, besides perhaps hopeful, highly remarkable. In the Netherlands, this aid organisation has been most shamelessly guilty of these kind of problematic images for years, with various TV commercials featuring hungry children in Africa and Asia who are defined by nothing but their misery. As a result, in the past few years, Save the Children Netherlands has always been nominated for the Fly in the Eye Award, for the worst campaign of a Dutch aid organisation. They have won the ‘prize’ three times.

Images reflect the colonial aid industry

Until now, Save the Children has always appealed to the so-called fundraising argument, i.e. 'shocking or simplistic images generate more money for charity'. It's an argument that many international NGOs use when they are confronted with the problematic images they use. As if the image is just a means to an end. However, it is time to consider communication as an integral part of development cooperation. A problematic campaign (which may 'score' among its supporters) is not an unfortunate or necessary by-product, but part of the problem of (failing) development cooperation.

We have to keep in mind that development cooperation has emerged from colonialism and its aim to 'modernise' non-Western regions according to Western models. At the end of the 1990s, Swiss professor Gilbert Rist wrote about the Eurocentric history of development cooperation and the continuation of colonial relationships and attitudes in the contemporary development industry. This industry flourished during the fabricated post-war world order of so-called 'developed' and 'underdeveloped' countries (or, as Jamaican-British sociologist Stuart Hall called it, 'the West and the Rest').

The suffering ‘Other’

The colonial relationships and attitudes can clearly be recognised in the communications of international aid organisations. According to Nandita Dogra, author of the book Representations of Global Poverty (2013), colonial representations of othering are characteristic of NGO campaigns, creating a difference between 'western' and 'non-western', 'developed' and 'underdeveloped ', 'modern' and 'traditional', and ‘saviour 'and' victim'.

Until the 1990s, images of the suffering Other, in particular of starving children in Africa, including hunger bellies and flies in the eye, were prominently featured in campaigns by Western aid organisations. During this period, an imagery debate started within the sector, in which such 'negative' and 'passive' images (often referred to as poverty porn) were criticised and replaced by 'positive' and 'active' images of poor people in the non-West, such as happy children (read: happy with the help) and entrepreneurial changemakers (read: entrepreneurial because of the help).

However, ‘positive’ images and other ‘innovative’ campaigns also often yield problematic images of othering. For example, the ‘positive’ exoticisation of the ‘Other', often according to the stereotype of ‘authentic poverty’, contributes to a colonial relationship in which poverty is mainly fascinating and inspiring for the Western 'self' instead of unjust and inhuman to the non-Western 'Other'. The most common problematic 'genres' we observe are stories from a saviour's perspective (often starring celebrities), playful simulations of misery, and the depiction of development work as an adventure journey.

‘Save the world for 3 euro’

Although we don’t encounter 'negative' images of poor, non-Western people who depend on Western aid that often anymore, they have certainly not disappeared. Until last week, Save the Children didn’t seem to intend to deviate from their ‘fly in the eye’ campaigns under the guise of the fundraising argument. In most of their campaigns, the depicted hungry children do not have a say and are only portrayed passively, waiting for Western help. The cause of their unfortunate situation, the structural inequality that often results from colonial times, remains unanswered and the solution is extremely simplistic (‘donate 3 euros a month to save these children!’).

However, Save the Children is not the only organisation that still exploits the fly-in-the-eye-genre. This year the Word and Deed Foundation took the biscuit with their campaign 'What if it was your child!’. Here we literally see a fly in the eye of an African girl (who and where she is, we don’t get to know), who tells us that she is growing up in an illiterate family. Then, out of nowhere, we hear a Dutch female voice: ‘What if it was your child!’

Then, employees of Word and Deed in the Netherlands share their childhood memories – ‘conviviality’, ‘attention’, ‘warmth from your parents’ – implying that the girl, and African children in general, miss all that. The contrast between the girl's youth and that of the employees is both misplaced and inappropriate, especially since it is not correct: the lack of education has of course nothing to do with a lack of parental love and affection, but everything with structural poverty and inequality.

White saviours

Another persistent phenomenon is the white saviour. We usually see two types of saviours in campaigns by aid organisations: donors who collect money in the Netherlands (often children), and ambassadors who visit a project abroad (often Dutch celebrities). For example, during Save the Children’s ‘Tacky Christmas Sweater’ campaign, where money was collected for ‘children in need’ worldwide, the emphasis was on celebrating the Dutch donors, who were invariably called ‘heroes’ and ‘rescuers’. In the epilogue to the movie the hysterical presenter, Dutch actor Eric Bouwman, even calls the day ‘most fun and heroic day of the year’.

The phenomenon of celebrities promoting aid work is called celebrity humanitarianism, and is controversial in the field of humanitarian communication. In the Netherlands it also regularly goes wrong. For example, two years ago, Dutch actress Nicolette van Dam was assigned the classic role of white saviour by UNICEF. In the video ‘Korm from Cambodia does not go to school’, literally every aspect of the difference between the actress and the suffering ‘Other’ is emphasised. From body posture to clothing and make-up, from the Western beauty ideal to non-Western poverty and from star charisma to passivity: everything distinguishes Nicolette van Dam from ‘child worker’ Korm.

And early this year, the Liliane Foundation sent Dutch actor Fedja van Huêt to Bangladesh to meet disabled children and their parents. Although he has conversations with them in the video, no child or parent is shown saying anything. We see the actor asking a girl a question, but the answer has been cut out. The ambassador embodies the quintessential Western volunteer tourist (which is, fortunately, highly controversial nowadays) who plays with and educates non-Western children, but above all gets an ‘incredible experience’ himself.

Simulating injustice

The Liliane Foundation also stood out negatively last year with their campaign ‘Restaurant Exclusion’, an example of the trend to simulate poverty or other types of non-Western misery. In the campaign video, Dutch celebrities run the risk of being left out from a luxury dinner based on their physical characteristics that are selected by a wheel of fortune. This is done to draw attention to the exclusion people with disabilities experience in ‘developing countries’ (yes, the term is still used). The total lack of context in the video suggests that the disabled Other (who, according to Dutch TV host Lucille Werner, ‘lives in a basement’), is portrayed as a victim of his heartless environment – and that it’s up to Dutch people to denounce this.

Such simulations are increasingly used as a strategy in Dutch campaigns, while they are in reality nearly always inappropriate – not only because the structural aspect of vulnerability is simply impossible to imitate, but also because the misery of the suffering Other is made to serve as an entertaining or educational activity in the context of Western privilege. What to think of 'Night without a roof' by TEAR (in which Dutch children stay 'a night in a slum', including an actual giraffe!), the 'Obstacle Run' by War Child (where every obstacle stands for a 'violent city' in the world), 'Lock me up' by Free a Girl ('we take care of the boxes of 1 by 2 meters', afterwards we organise a 'grand party!'), and 'Face It' from Doctors without Borders (where the faces of Dutch celebrities were painted as if they had ebola)? The last campaign was removed after fierce criticism.

On a journey to a better world

Simulations are part of ‘innovative’ campaigns designed to rally supporters for the organisation and, bottom line, to raise more funds from the seemingly saturated and poverty-fatigued audience. A different (but comparable) campaign to enthuse supporters is the adventure journey – perhaps the most striking problematic trend in recent years. Campaigns such as 'Cycle for Plan', 'Red Cross Expedition' and 'Travelling with Habitat' exemplify the growing trend with bitter aftertaste in which aid work goes hand in hand with an adventurous journey, usually in the form of a, to stick to colonial terms, 'expedition'.

In the appealing advertisements and lyrical epilogues of these 'ultracool' journeys, the emphasis is usually put on the heroism of the sporty Dutch participants and the exoticisation of the 'unspoilt' and 'rugged' landscapes that they explore and the 'special' and 'powerful' people they encounter. Time and again development aid seems to support the personal development of the participants rather than the other way around.

The portrayal of the Dutch donor, ambassador, participant or traveller as a helper is central to all these problematic genres. They are always placed on a pedestal, while the people being helped seem to be of secondary importance. This is not only painful, but it also undermines the core values that should underpin development aid.

This fits in with a political trend: an increasing share of development money, intended for international solidarity, is nowadays used to stop (and thus not be in solidarity with) refugees from Africa and the Middle East. Such a shift is only possible when core values of equality and humanity are side lined, which, in turn, has everything to do with the way of communicating.

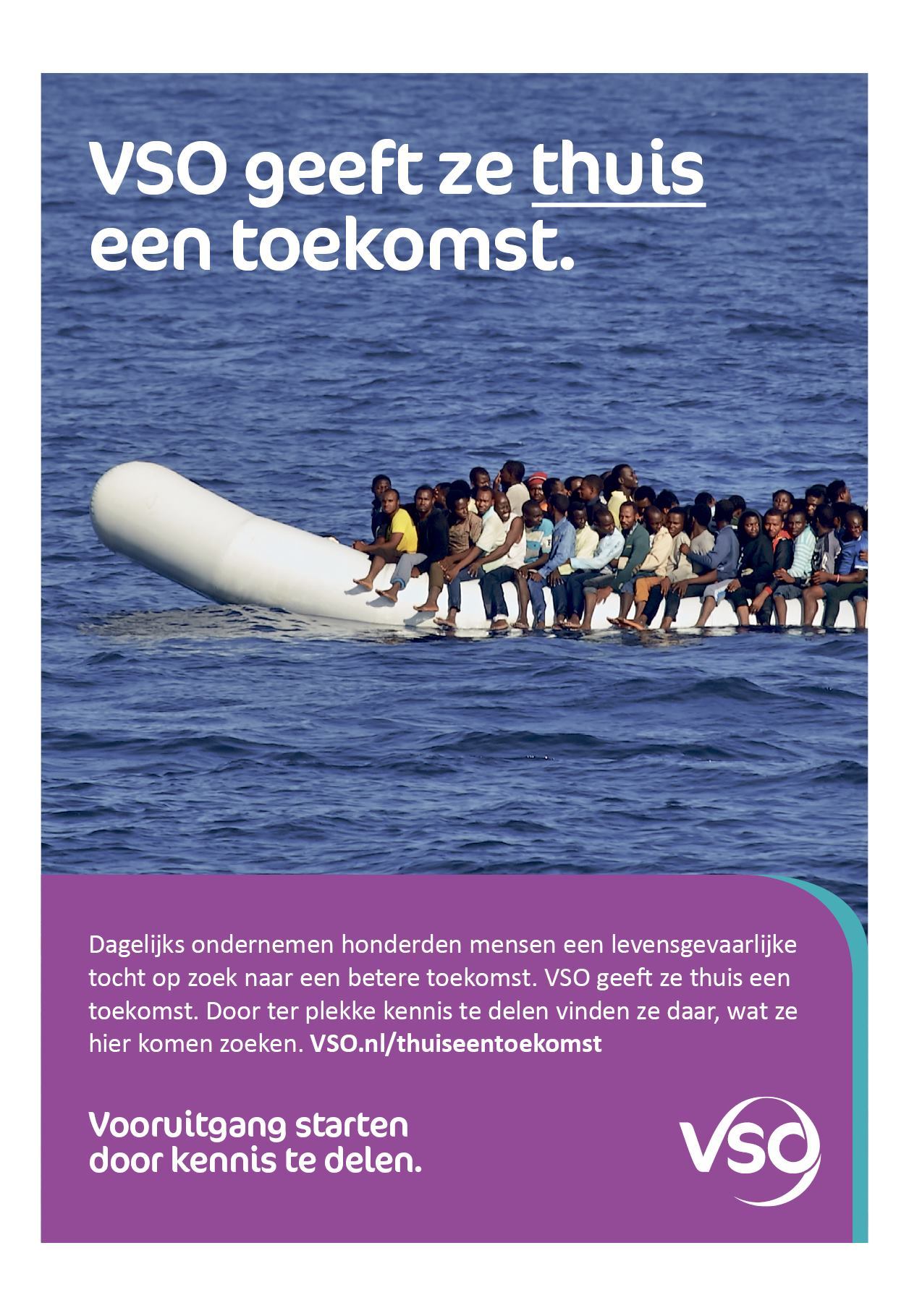

For example, VSO Netherlands used iconic images of boat refugees in the Mediterranean for a shocking billboard campaign entitled ‘Give them a future at home’, whereas Health Works used a similar anti-immigration rhetoric. Here too, development cooperation and its communication are inextricably linked: while white rescuers focus on 'discovering' the world, the future of the suffering Other lies 'at home'.

Equality and humanity

What, then, are solutions to all these imagery problems? They have to be sought in a practice of, and communication about, development cooperation in which values such as agency, equality, solidarity, and above all, humanity are central. There are organisations that succeed in this, which is evidenced by the High Flyer Awards, for the best campaign of an aid organisation. Here, images are usually based on the perspective, self-reliance, equality and dignity of non-Western people, with the campaigns painting a more complex, nuanced and ‘complicit’ picture of vulnerable situations in the non-West.

Still, we have to remain vigilant, because colonial attitudes and relationships are deeply rooted in development cooperation. The aid sector, and thus its campaigns, is still too often characterised by Eurocentric practices and images which we must continue to question critically until they, to end with Stuart Hall, become ‘uninhabitable’.

Postscript

Last Wednesday, June 30th, Emiel Martens discussed the OneWorld.nl article with Pim Kraan, director of Save the Children Netherlands, in the Dutch radio program De Nieuws BV. It soon appeared that the statement of solidary with the Black Lives Matter movement was mainly for window-dressing, at least for the Dutch branch of Save the Children. Kraan insisted that Save the Children's previous campaigns didn't include racial stereotypes and white saviours. Their problematic TV commercials that 'strip the agency and dignity of children' were again shown on Dutch television the very same evening. You can check the full broadcast here (in Dutch).

The IDleaks Awards were originated five years ago by IDleaks (soon Expertise Center Humanitarian Communication), a non-profit organisation that is committed to better humanitarian communication. The aim is to make Dutch NGOs aware of the importance of good communication and to rebuke them when they produce stereotypical or other unethical images. You can vote for the IDleaks Awards until 8 July, 12.01pm. The winners will be announced that same evening. Artist and anti-racism activist Quinsy Gario, filmmaker and performer Emma Lesuis, journalist and columnist Carol Rock and human rights lawyer Nani Jansen Reventlow will choose the Jury Prize this year.

This story was first published in Dutch in OneWorld.

The winners of the 2020 Fly in the Eye and High Flyer Award were announced early July.