On April 30th 2025, Maasai youth disrupted the signing of a carbon offsetting project agreement in Kajiado county, Kenya. On the face of it, they had simply rejected a controversial carbon project. However, as ZAM's partners at Africa Uncensored found, their actions would also expose unprecedented land fraud perpetuated by powerful figures, including proxies and associates of current and former elected officials

Ol Donyo Nyokie, spanning 168,000 acres and home to over 1,000 Maasai households, is one of several community cattle ranches that had been listed as “participating communities” by Soils for the Future Africa (SFTA) and US-based Carbon Solve, two organisations that undertake carbon offsetting projects in Kenya. The two ranches are part of the 1,5-million-hectare Kajiado Rangelands Carbon Project (KRCP). With the approval of authorities including the Kajiado County Government, the offsetting project seeks to undertake soil carbon sequestration through ‘sustainable land management practices’ – in this case by managing livestock grazing patterns to preserve vegetation. This activity generates carbon credits, which are certificates representing one ton of CO2 or equivalent greenhouse gases that have either been removed from the atmosphere or prevented from being emitted.

The credits are sold to companies like Shell and Volkswagen

This project represents the latter – keeping rangelands intact and restoring grasslands by introducing rotational grazing in some places, and the credits are counted as emissions that have been prevented. These credits are then sold to companies such as Shell and Volkswagen, and the benefits were then supposed to be shared with the community.

Clash with the youth

On April 30th this year, the KRCP’s attempt to enter Ol Donyo Nyokie would open Pandora’s box. A ceremony in which SFTA was set to seal its entry into Ol Donyo Nyokie was disrupted by hundreds of young, mostly Gen Z Maasai youth, known as morans (warriors). The violent clash between youth opposing its entry and the mostly older people supporting it left at least seven people badly injured.

Over the course of six months and several trips to Kajiado county, Africa Uncensored and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) dug deeper in search of answers on the growing fractures in Maasai communities living in Kajiado – analysing hundreds of documents, conducting interviews with key figures and utilising satellite imagery and other OSINT techniques.

On the face of it, the youth had simply stopped the entry of a controversial carbon project. In reality, that was only the tip of the iceberg. Powerful and connected political elites in Kenya are executing a massive, silent land heist while major international organisations either knowingly or unknowingly provide cover under the guise of carbon offsetting projects.

Powerful political elites in Kenya are executing a silent land heist

Bait and switch

The Kajiado Rangelands Carbon Project first sought to operate in the Ol Donyo Nyokie group ranch in 2021. Community meetings highlighted early divisions as the topic was broached. According to Gideon Kanchory, one of the Maasai youth who mobilized to shut down the meeting on the 30th, told us that it had been a problem since day one.

“We asked questions and that was seen as being disrespectful,” Kanchori said. While some youth had initially expressed reservations over the project, lack of transparency and detailed information, many older people were on board. “Walisema hii ni baraka tele, they said this is a great blessing”. In addition to the promised cash benefits from the carbon credit agreements, group ranch officials told members that the carbon project would be a solution to their long-sought after search for title deeds to enable individual ownership. Members who wanted the land subdivided didn’t have the millions of shillings needed to pay survey fees and other costs associated with processing title deeds. Owning their land would allow them the associated benefits, such as the ability to sell it, something many wanted to do to aid their economic situation.

“We asked questions and that was seen as disrespectful”

Representatives of Soils for the Future Africa took part in meetings where the carbon project was discussed as a solution to their land ownership problem. David Nchui, chairman of Oldonyo Nyokie, told the press that an initial payout of KES17 million (US$131,000) to be gained from the project would pay Geoflex Consultants, a surveyor, to cover the fees needed to complete the subdivision of the group ranch. “Tulishakubaliana kama jamii hio pesa tulipe survey fee. Tumeshakata shamba, imebaki kupeana title”, he said, meaning: “We have already divided the ranch, all that’s left is to give people their titles. We had agreed as a community that the money would be used to pay survey fees.”

A contract obtained by Africa Uncensored between Ol Donyo Nyokie group ranch and Geoflex Consultants signed in 2021, states that “each member shall get equal and appropriate share of the land in accordance with the scheme plan or scheme plans to be prepared by the surveyor.”

Beneficiaries

So this was the deal, according to the chairman of the group ranch. SFTA would pay KES17 million as a “motivation fee” for the community to see “benefits” before the project even started generating carbon credits. The 17 million shillings would be paid by the group ranch to a surveyor – Geoflex – to enable the members to get their title deeds. SFTA through KCRP would then engage in soil carbon removal by managing livestock grazing patterns to preserve vegetation, and this activity would generate carbon credits for sale on the voluntary market. The proceeds from the credits would be shared with the community.

You might think this would be a win-win for the community, but you would be wrong. Our investigation found that it was not just the registered members who would benefit, and among the beneficiaries definitely weren’t the thousands of younger members of the community: they would not get any land by virtue of not being formal members of the group ranch.

The list revealed connections to senior Kenyan politicians and their proxies

A key document – an area list of beneficiaries drawn up by the surveyor – ultimately determines who gets the titles in the subdivision process. We obtained copies of the area list separately stamped by the surveyor, Charles Ameso Ang’ira of Geoflex, and the Kajiado Lands Registry. What we saw was shocking. Dozens of non-members had been allocated large parcels of land, including multiple companies. The process was highly skewed, and group ranch officials and their proxies had been allocated at least 1,000 acres of land. A further dive into the companies on the list would reveal connections to senior Kenyan politicians and their proxies.

Parcels for friends

Two of these companies, Pinehub Limited and Midlands Limited, were allocated a total of 360 acres. Documents from the Companies Registry show that Rose Wamaitha is registered as a director of both companies. Wamaitha is a known proxy of the family of former President Uhuru Kenyatta in multiple companies. In July 2025, Rose Wamaitha’s connection to the Kenyatta family was revealed following a tax dispute, in which a company registered under her name inked a controversial deal with the contractor working on the KES88 billion Nairobi expressway toll road.

Another of the companies on the list is Elnum Business Solutions, which was allocated 92 acres. Company records show that a Mr Rotich Wilson Kipngeno and Ms Emily Chepkirui Kiprotich are listed as shareholders of Elnum Business Solutions, and they both have addresses in Bomet, a county in Kenya’s South Rift region. A dive into its ownership would reveal that Elnum, through another company, held a stake in Edmina Solutions Ltd. One of Edmina’s registered directors is Edna Lenku, wife of Kajiado Governor Joseph Ole Lenku.

The surveyor himself received land

Naomi Nchui, the wife of the chairman of Oldonyo Nyokie group ranch, David Nchui, was allocated a total of 780 acres, making her the single largest individual beneficiary of the subdivision process. The vice chairman was also a major beneficiary, receiving 363 acres. Geoflex Consultants, owned by surveyor Charles Ameso Ang’ira, was allocated numerous parcels of land. Some of the parcels were registered under both Geoflex and the group ranch while others were solely under Geoflex.

The people of Ol Donyo Nyokie simply wanted to own their land. But if the youth had not stormed that event on April 30th, and stopped the process, the funds would have been paid to the surveyor and the subdivision process according to the list above would have likely gone on without a hitch.

Big Life

The Kajiado Rangelands Carbon Project is present in several other group ranches in the county – including Eselenkei, Olgulului, Ololalarashi. Unlike in Ol Donyo Nyokie, where the subdivision remains pending, the subdivision process was already done in some of these ranches, such as Eselenkei. Members in such ranches have received title deeds, and some subsequently sold off their pieces of land. However, the new owners, some of whom had begun to invest heavily in large scale farming, were neither consulted nor informed about the carbon project’s entry, and as far as we could access, the company Soils for the Future did not seek the consent of individual landowners.

In Eselenkei, residents, with the notable exception of a senior Kajiado county government official, who maintains a large farm and residence in the area (satellite imagery confirmed the existence of the tilled farm along with a house), were now being stopped from farming and building. The county government set up barriers blocking access for vehicles carrying construction materials and farm equipment. According to reports from the community, some properties were then even destroyed and farm owners assaulted, allegedly also by rangers working for Big Life, an international conservation NGO that had partnered with the county in the carbon credit project, together with county officers and police. (Big Life has denied any involvement, see below.)

Local authorities “destroyed farms and assaulted owners”

In October 2024, the Golden Fields Residents’ Association moved to court challenging the Kajiado county government and Big Life over infractions including “illegal carbon trading on private property”. The association stated that they had faced assault and destruction of their property by Big Life rangers, county officers and police, and questioned the county’s moves to change spatial planning laws without consultation. In March 2025, the landowners also complained to the Independent Policing Oversight Authority IPOA, about rising cases of harassment, assault, and intimidation allegedly orchestrated by Big Life Foundation rangers, Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) officers, and county officials.

On our visits to Kajiado we verified multiple such reports of destruction of property on farms in the area, including cut fences, destruction of solar panels and irrigation systems, and damage to buildings. One worker at Riverstone Farms in Eselenkei reported having sustained injuries on his head after being assaulted after the farm was stormed by Big Life rangers. “They said they’ll use me to send a message, that they don’t want to see anyone at the farm. They almost killed me”, he told us.

On 16 June 2025, the Environment and Law Court at Kajiado rejected the residents’ petition, stating that it had no jurisdiction on the issue of human rights violations but only about land use, adding that it could not determine whether consultation with communities had been sufficiently part of long-term spatial planning. During the case, the Big Life Foundation denied any involvement with the actions complained of in the petition and asserted that the petitioners had no cause of action against them. The state agencies all responded that they had followed national policy. IPOA, the police inspectorate, has not responded to date. Similarly, authorities including the Ministry of Land and the Kajiado County Lands Adjudication Office have failed to furnish the community with the official area list and survey map despite repeated requests.

Soils for the Future responds

In response to queries from Africa Uncensored, Soils for the Future admitted that private properties had been listed as part of the project area, blaming it on “rapidly changing land ownership.” The organisation said it was updating its maps to remove privately owned land parcels. “Land continues to change hands in the project area rapidly as people sell land”, Soils for the Future said, adding, “this information is not easy to obtain since it’s their personal property. We have been updating our maps (removing privately owned land parcels from the project, whose owners do not want to be part of the project) and we do this every time we discover that the ownership of a given piece of land has changed.”

Building in a National Park

In a statement following the signing of its agreement with the KRCP in June last year, the Kajiado county government announced that the project would also support conservation and mitigation of climate change in the Amboseli National Park by managing grazing patterns and generating carbon credits. The MoU signed between the county government and Soils for the Future would also see the organisation undertake biodiversity surveys in the park and determining home range sizes for various animals – the area an animal uses for its normal activities like foraging, mating, and raising young.

However, visiting the park, considered one of Kenya’s crown jewels, we found two major construction projects, one a collection of 22 luxury lodges being developed on the Kitirua wildlife corridor, potentially affecting the free movement of animals, and another, a luxury hotel under development, with numerous workers quarters and materials spotted. The construction would seem to violate strict regulations for the construction of any structures within national parks and wildlife corridors in Kenya. According to workers and residents whom we spoke to, the two projects are associated with a senior county government official and a senior national government official. We sought to independently verify their ownership, but could not find official documentation. The Kenya Wildlife Service and National Construction Authority have so far not responded to queries regarding the construction activities in the park.

Damaging consequences

At the 27th United Nations’ Climate Change Conference in 2022, Kenya’s President William Ruto declared that carbon credits “will be Kenya’s next significant opportunity.” He continues to present these as a possible massive economic boost for the country, particularly with the demand for carbon offsetting expected to rise alongside data centres and power plants meant to power the AI era.

In line with this promise, Kenya has passed the Carbon Act to guide the regulation and management of carbon projects in the country. But experts worry that the influence of Western conservation organizations coupled with systemic and individual corruption in Kenya means that large populations could be vulnerable to damaging consequences of carbon offsetting initiatives. “The sad situation is in Kenya right now, I can tell you, our whole state system, from the very top to the local people, nobody understands just how valuable our natural resources are. Not one single person. Even the minister has no idea,” says conservation scholar and author Mordecai Ogada. Ogada feels that “these legislations are put in place to pave the way for those who want to come and annex these things.”

“These legislations pave the way for those who want to annex these things”

He added that “without a Carbon Act, there’s no way Soils for the Future can come and legally grab land in Kajiado. But we created that act to pave the way for them. They’re the ones who even pay for the meetings. These parliamentary retreats and all that, they pay the per diems and all that. And these acts are created to help them.”

The same pattern has emerged even from the time of the Northern Rangelands Carbon Project in Northern Kenya, which generated and sold credits to companies including Meta and Netflix, while stoking tensions within pastoralist communities as it clashed with their ways of life. Carbon credit certifier Verra suspended the project earlier this year after the conservancy hosting it, -which sat on community lands-, was declared unconstitutional by Kenyan courts. This stopped the project from selling any further credits.

Due to cuts in US government funding and support for carbon credit programs during the second Trump administration, organisations in the field are increasingly looking for more favourable locations to establish their operations, and it seems Kenya is prominently on their list. “And that is how you colonise a country in the 21st century. In the 19th century, you came with guns and shot people and all that. 21st century, you come and tell them you’ve come to save them. And you pay their legislators to come up with the laws that favour your saviourism,” Mordecai Ogada says.

Impact

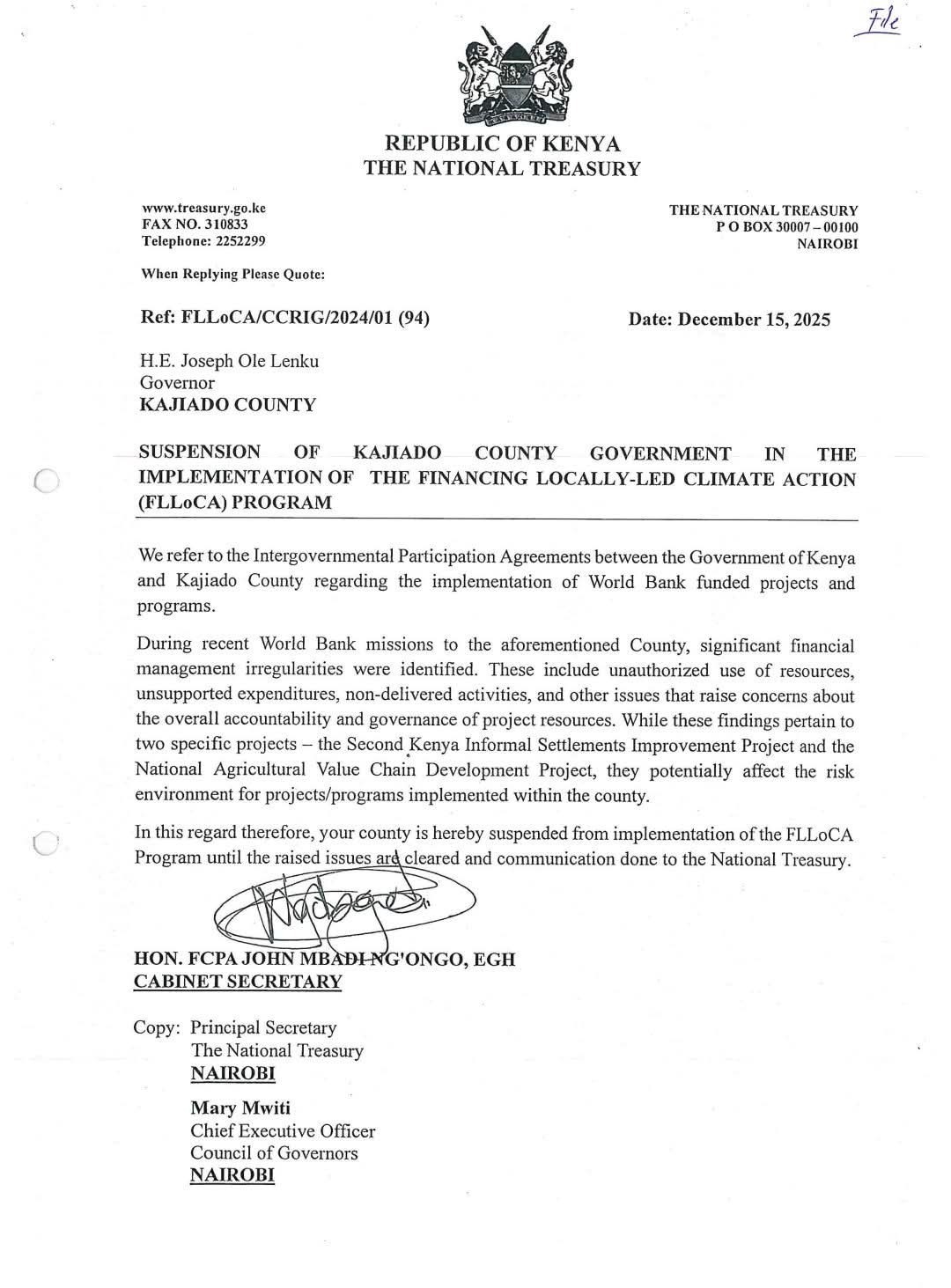

On 18 January 2025, exactly a month after Africa Uncensored’s documentary on Carbon Credit projects was aired on YouTube, the Kenyan government suspended Kajiado County from its Climate Action programme. The suspension was officially based on “World Bank missions to Kajiado County, which identified several financial management irregularities, including unauthorized use of funds, unsupported expenditures, activities that were paid for but not delivered and other weaknesses in accountability and governance”, a letter to Kajiado from Kenya’s Treasury said.

See the original story by Africa Uncensored here. See the documentary here