Undaunted

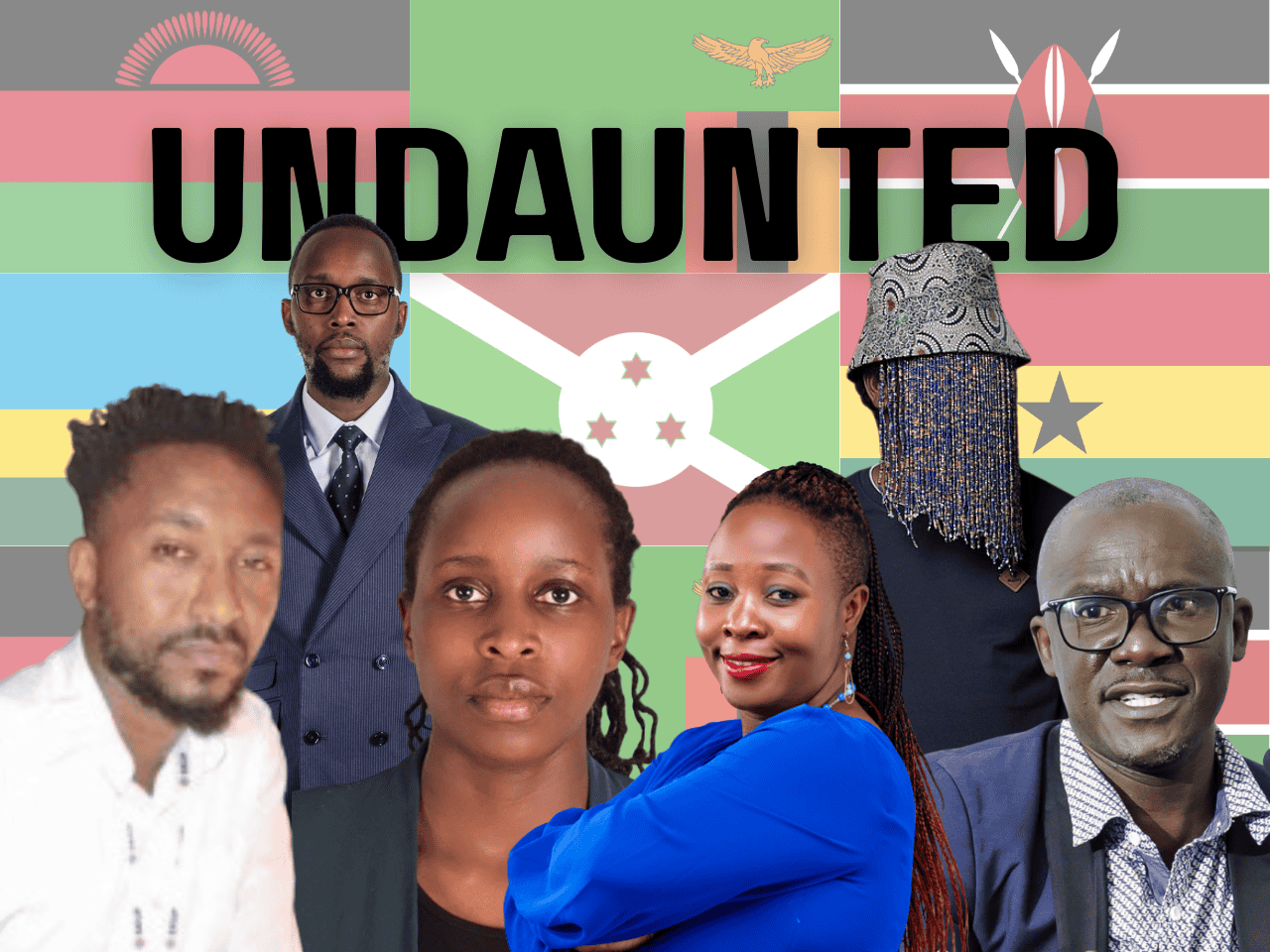

They have often had to survive on very little, faced threats both physical and legal, been routinely slandered in online campaigns orchestrated by the powerful, and sometimes forced to work undercover or from exile, but they enter 2026 smiling. ZAM portrays six journalists, members of the NAIRE Network of African Investigative Reporters and Editors, who attended milestone pan-African and global investigative journalism conferences last year, about taking stock of 2025 and their plans for the New Year.

“We got our government to force a corrupt contractor, who had absconded with the country’s money, to come back and repair a road that was so bad that children playing nearby were getting killed by veering vehicles. We stood together with the community on that,” says Ghana’s best-known investigative journalist, Anas Aremeyaw Anas. In Kenya, data expert Purity Mukami hopes her work exposing nepotistic state contracts benefiting the “nieces of politicians” has contributed to the passage of a new law requiring mandatory wealth declarations. Meanwhile, her colleague Gilbert Bukeyeneza, operating from exile in the Great Lakes region, sighs with relief when reflecting on his Ukweli Coalition Media Hub for establishing vital cross-border reporting with a team in which “each member has grown up in war and crises.”

“There is a change”

Down in Zambia, Charles Mafa, cofounder of the Makanday Investigative Journalism Centre, smiles as he announces that he is on his way to pick up a response from his country’s Treasury to a query he submitted on a financial matter. “Previously, they would not even talk to us. But there is a change.”

An important role in establishing investigative journalism as a force to be reckoned with against often oppressive regimes in their countries, they say, has been the growing international amplification of stories produced by NAIRE. “One story, on Russian recruitment of our citizens for drone factories, has even reached a TV news programme in Japan,” says Mafa, adding that politicians in his country tend to “sit up straight when the noise is also coming from outside.”

In the case of the “Russia” story, the noise arose from a seven-country collaboration on the ZAM platform, which exposed the exodus of young African women to Russia for deployment in that country’s war machine, a phenomenon that their own governments either ignored or actively facilitated.

Accountability behind closed doors

The journalists are not claiming that their politicians have suddenly reformed. “Of course, we are still dealing with people who can kill,” reflects his colleague from Malawi, Josephine Chinele, recalling a case in which a member of the country’s anti-corruption bureau was murdered. “But we are becoming more respected and credible as journalists. People are noticing that we don’t just write whatever we like, that we are exposing real ills and that there are real, accountable people behind closed doors.”

Chinele is particularly proud of the ‘Legal Rebels’ investigation, also a cross-border project, which highlighted how committed lawyers in five African countries, including Malawi, strive to address a justice system that, in her words, “unfairly advantages the rich and punishes the poor.” “The story we did, where we compared a rich man and a poor man, people were forwarding it on WhatsApp, talking in groups, things like that. People now know that this happens, and they have been engaged with it.”

“We are still dealing with people who can kill”

Another example of noise that helps “when it comes from outside” is the court case won in March 2025 by Anas Aremeyaw Anas in the US, in which a notorious millionaire and politician in Ghana — who had defamed Anas as an “extortionist” and “murderer,” and whose earlier hate speech against a colleague of Anas was thought to have contributed to the colleague’s actual murder (1) — was convicted and ordered to pay damages to the journalist. “The fact that a journalist was able to haul the politician before a US court is unprecedented. That politician’s career is now not working because people are calling him a liar. This sends a message that politicians mustn’t take journalists for granted — that we can take the battle to them.”

Mukami immediately agrees that international support makes a significant difference. “I would not be here (attending conferences and being invited to workshops on new, better laws) if our story on the wealth of Kenya’s first family had not been part of the Pandora Papers. It would have been blocked here in Kenya. Through our international partnerships, we benefited from legal resources that helped proof the story and make it watertight, in a way that we simply cannot do in our own newsrooms. Our editors are often very competent, but they don’t have the time or the money.”

“Chasing shadows”

All six NAIRE members have in 2025 been invited to pan-African and global investigative journalism conferences, presenting on undercover work, working from exile, trying to find data, “chasing shadows” as Mukami calls it, in Africa’s data-poor environment, and highlighting the transnational investigations done with the ZAM platform. Some also contributed input on the mental health challenges they face. Gilbert Bukeyeneza: “In our Great Lakes region, all of us are carrying wounds. There has been strife for decades. Many of us, like me, my father was killed because of politics when I was seven, have suffered violence and losses. The worst thing is, we have never had justice. No witness to record what happened. No stock taking, no truth searching. It just stays with us; it festers. Our families will tell us: these are the people who killed so and so. My drive for our work is that it must not continue to impact on the next generations. I am so happy when I see that our team members, who all come from different backgrounds, countries, and ethnicities, are now going back to their communities and doing this reporting, which serves to make sense of it all.”

“In our region, we never had justice”

Agents and colonialists

Politicians and other powerful postcolonial elites in African countries, when outed in investigative stories, often retaliate by calling journalists “agents of the West” or “puppets of colonialists,” arguing that only ‘colonialists’ would criticise an African government. The label does not faze the NAIRE members. “Of course, they call you agents,” says Chinele. “But when people are throwing stones at you, you know that they have an agenda. And that agenda is to stop you. When they come with their accusations, I always say: OK, bring evidence that we were paid to write this. And our stories stand up.” Aremeyaw Anas: “It makes no sense. If the West came to colonise us, it’s OK for our politicians to now defraud the public? Can you really make this argument?” “Anyway,” says Mukami, “when they said it about us, some people checked and found that the West was paying our government way more than our international partners were giving us as media.”

“The West was paying our governments more”

Rwandan Samuel Baker Byansi, now busy with his second book, Modern Dictatorship, on Rwanda’s autocratic leader Paul Kagame, deals with the accusation of being an ‘agent’, a claim propelled and multiplied by the Rwandan regime every day of his exiled life. “Some in the West are influenced by the narrative that it is bad to criticise Kagame, or any African government. But the West must question their role in these people becoming presidents in the first place. The West has contributed to who Kagame is; he gets all his power from the Western world. So if he kills people in Congo and people in Congo are asking the Western world to please stop Kagame, must you not listen to them? The colonial structure that is still in place (through such regimes) still allows the Western world to have access to African countries.”

Gilbert Bukeyeneza feels that the West accommodates oppressive African governments too much. “Western governments know very well that when they criticise an African government on human rights, that government will turn their back and go to China. So they often stay silent. All they care about is stability and their own interests in contracts and natural resources.”

Elections dawning

In 2026, when both Zambia and Kenya will be preparing for elections, the question of who in the West is supporting whom is becoming acutely important, Mafa and Mukami say. Charles Mafa: “The funders of these candidates are often external (Western) people, as in the case of our current president, Hichilema. In 2021, this president was elected with so much promise and hope, but because he was supported by the Tony Blair Initiative and the Brenthurst Foundation, now defunct [see (2)], he now pays more attention to those external people and not to the voters. Campaigns are very expensive, candidates fly around in helicopters, who pays for that? The ones who fund the road to the presidency include companies that want mining contracts.”

In contrast, Mafa adds, “If it were the voters supporting their candidates, even if it’s a farmer selling a cow for that purpose, we could have candidates with no ties to outside forces. I would prefer to see international pro-democracy funding helping these communities in that way or supporting credible organisations that can play a watchdog role in the electoral process.” That is especially urgent now that community organisations are being cut off by the US. “One recent US visitor to Zambia, one of Trump’s people, said that ‘they are removing the middleman,’ meaning the civil society organisations. They now only want to work with the government. And in Africa, that is the worst. Government already has all the resources. Resources need to be put on the ground, like community-rooted organisations and independent media.”

The Trump administration has cut off civil society

In Kenya, Purity Mukami is concerned about dull “he said, she said” reporting on electoral candidates, which she hopes mainstream media will move beyond. “Our people are quite well educated. If you don’t give them something with depth, they will abandon you and go to the internet, to TikTok. And nowadays, fake news is almost like the real news. Politicians pay money to broadcast their own narratives. So there is a lot of work to be done for us (journalists).”

Elections can come with violence, too. Recently, the ruling regime shot scores of protesters in the streets of Nairobi. Do journalists in Kenya have reason, once again, to be scared? “Of course you have to be scared,” Mukami says. “And it is not just physical violence. They [powerful politicians] openly attack newsrooms, call you names, and conduct online campaigns to discredit you. And many mainstream newsrooms depend on government advertising.”

Being like a hummingbird

But what keeps her going amid all the corruption and power abuse, she concludes with a smile, is Nobel Prize winner Wangari Maathai’s story of the hummingbird that “brings drops of water in its beak, flying up and down with one drop many times, to put out a fire in the forest. The lions and the elephants, with their big trunks, and they could bring much more water, are watching, saying, ‘what can you do, you are so small,’ but she keeps doing it. This is what helps me. I tell myself I am like the hummingbird. I even tell my daughter that story, it’s animated, we have watched it a million times. I never want her to feel discouraged or insignificant.”

The group puts much of their hopes for 2026, again, in strength in numbers. “We are definitely gearing up around the country for the elections,” says Mafa. Gilbert Bukeyeneza wants, he says, to further strengthen journalism’s impact at the community level. “I have been amazed at what the reporters managed to do, even if they are often looked down upon as ‘just local.’ I have seen people feel validated, telling our own stories. It tells me we are on the right track, providing a professional framework, editorial support, and some resources to travel. I hope to be able to equip our Ukweli Media Centre with more editorial back-office support, training, and guidance.”

“I feel I can do anything”

Josephine Chinele also feels much stronger than when she was working as an individual reporter for a paper in Malawi. “Those days we would be told how to do or not to do a story because it would conflict with an advertiser, or sometimes my story would be killed altogether.” Now, “invited to conferences, and working with a national investigative journalism platform, the PIJ, and affiliated with NAIRE and ZAM, I am in the right space. I feel I can do anything.”

Mukami will likewise continue to draw strength, she says, from the NAIRE group. “It puts people together, and we gain confidence. It is useful to see the patterns and interests in the different countries, like in timber trafficking, arms trafficking, and mining. And if it wasn’t for this group, I could not go up to Anas and say hello.” Anas, for his part, says he is “looking forward with lots of smiles: 2026 is going to be a dramatic year, with many projects, not just for Ghana but for the world.” He can’t talk about the subjects yet, he says, before ending with his trademark comment, “Stay tuned.”

“2026 a year of solidarity”

Samuel Baker Byansi is set to make “2026 a year of solidarity,” he says, “with the citizens who ask for social justice in Africa. And not only there. We should all align with people who are looking for positive change in their communities, because that also gives security to the rest of the world.” He raises migration as an example. “This migration issue in Europe comes from people who have to leave their countries because of insecurities and other problems. But some European governments choose to side with people who cause these very problems. Not only with Kagame, but also in Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya. And Israel, of course. When you see a state like the US sanctioning judges of the International Criminal Court, sanctioning ICC prosecutors, that sets a very bad precedent. The ICC should play its role, and international laws should be applied, also in the case of African dictators. Or do the same values not matter when it comes to us?”

- Millionaire politician and businessman Kennedy Agyapong, a key figure in one of Ghana’s main political parties, has conducted a war of hate speech against Anas and his team, calling Anas a “thief,” an “extortionist,” and even accusing him of murder. But it was Agyapong’s hate speech that is considered to have been a factor in a real assassination, namely that of Anas’ colleague Ahmed Suale in 2019.

- The Brenthurst Foundation, which closed its doors in 2025, was a Johannesburg-based think tank established by the mining Oppenheimer family “to promote debate and policy advice for accelerating Africa's economic growth.”

* Josephine Chinele was invited to the Global Investigative Journalism Conference but was unable to attend due to a family emergency.

Virtually all investigative and public interest reporting in Africa depends on support from those who help these journalists' struggle for democracy, transparency, accountability and social justice. Please help support the work done by NAIRE members such as the ones interviewed above. Donate to ZAM with the mention ‘investigative journalism platform’.