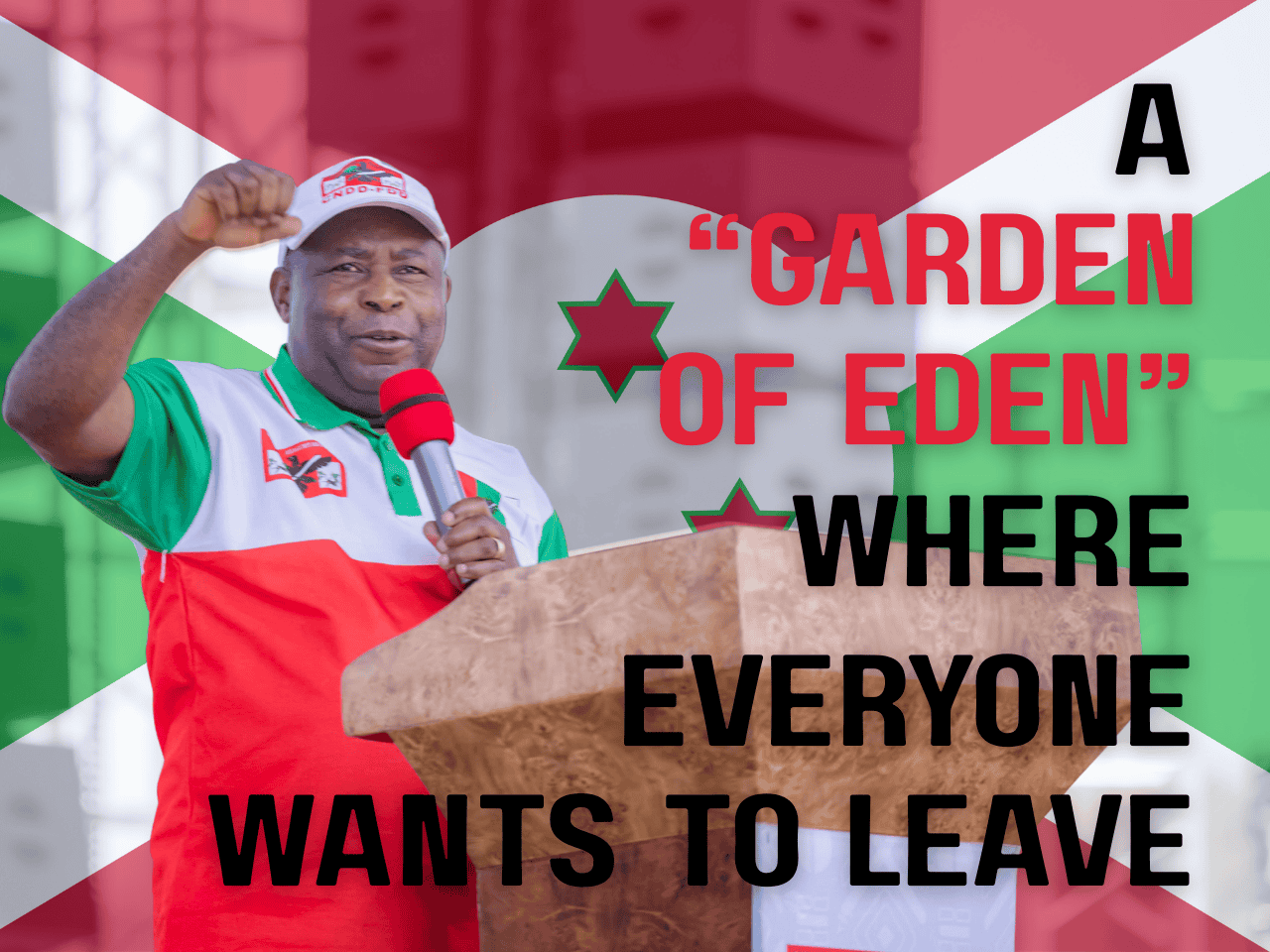

Burundi’s new capital, the showcase city of Gitega, is dressed to the nines, celebrating itself — in the words of the president — as a “Garden of Eden”. Yet behind this façade lie deep-seated economic and political crises. Thousands of desperate young people are leaving their homes to try their luck in neighbouring countries.

In Burundi’s new capital city, Gitega — the birthplace of the current president, Evariste Ndayishimiye, and declared the capital in 2019 — new hotels and businesses (particularly building-material stores) are opening everywhere. Citizens navigate this apparent splendour amid the daily sound of sirens blaring through the streets to clear the way for a minister en route to a conference, a high-ranking army officer visiting his farm, or a senior official of the ruling party returning from a political meeting.

Sirens clear the way for the officials

But when one looks away from the vast construction sites and turns instead to ordinary citizens in the streets and on the hills, a different picture emerges. Outside the Matergo, a popular new hotel frequented by officials, diplomats, and businesspeople, two vehicles are parked side by side, fuel tanks open. A man stands between them, siphoning petrol from one car to fill the other. “It’s a good deal,” whispers a passer-by. “The buyer may have offered him five times the normal price, or even more. That’s the new business here, if you have a car. You queue for days at a petrol station, and if you’re lucky enough to get fuel, you sell it to someone who isn’t willing to wait. My country is in bad shape.”

The man looks around nervously to ensure that his words have not fallen on prying ears. To say that the country is in bad shape, that the lives of its citizens are at a standstill because of a widespread fuel shortage now lasting more than three years, is to challenge the official narrative of a nation flowing with milk and honey. There can only be joy in the ‘Garden of Eden’, as President Evariste Ndayishimiye christened Burundi in a speech in February 2024. Police and ruling party militias are everywhere; the streets have ears, people say here.

Powerful generals

Behind the glitz of Gitega’s hotels and mansions lies a Burundi currently ranked as the second poorest country in the world, just ahead of South Sudan. Traditionally, the country has relied on international aid as its main source of foreign currency, primarily from the European Union, but this support ended in 2016 following the regime’s refusal to engage in dialogue with its opponents. Burundi is now increasingly characterised by volatile politics (inter alia driven by internal conflicts among powerful generals), an economy in dire straits, 87 per cent of the population living on less than US$1.90 per day according to the World Bank, and widespread corruption and embezzlement. The full extent of this corruption remains unknown due to the absence of independent media or monitoring institutions. At the end of 2023, when he was sentenced to life imprisonment for attempting a coup d’état, it was revealed that Alain-Guillaume Bunyoni, the former Prime Minister, owned nearly 150 houses in Burundi’s economic hub, Bujumbura, alone.

Meanwhile, not only Gitega, but the entire country are under heavy surveillance. Parliamentary and municipal elections in June 2025 took place in a context of political lockdown: most political opponents have been in exile for 10 years, and those who have remained in the country have almost all been silenced. As a result, the ruling CNDD-FDD secured 100 per cent of the seats in the National Assembly at the end of the election, a North Korea-style score never before achieved by any other party since the introduction of a multi-party system in the 1990s.

In the streets of Gitega, tension is palpable. Hundreds of members of the youth wing of the ruling party, the Imbonerakure — described by the United Nations as a militia — roam in jogging gear, sometimes armed and wearing combat uniforms, chanting martial songs as police carry out rigorous checks. Rumours of “rebels” infiltrating the country are rife. Police search for weapons caches under car seats, in boots, everywhere.

The regime fears Rwanda’s rebels at the gates

The feared “rebels” are the Rwanda-backed M23 militia, which has wreaked havoc in eastern DRC and is now, Burundi’s government says, at the gates of Bujumbura, the former capital. Bujumbura is only a four-hour drive from the DRC city of Bukavu, where M23 now reigns.

The Burundian regime’s diplomatic relations with Rwanda have been abysmal for nearly a decade, a situation that heightens fears that the war in eastern DRC could spill over onto its territory. The threat dates back to 2015, when hundreds of thousands of Burundians fled into exile following then president Pierre Nkurunziza’s decision (he died in 2020) to seek an unconstitutional third term, triggering a major political crisis. After Rwanda took in large numbers of these refugees, the Burundian regime has persistently accused Kigali of harbouring rebels intent on overthrowing it.

Beer for the party

Curiously however, Burundi’s police are not just searching for weapons, opponents and rebels. It is also beer: Primus and/or Amstel, products of Brarudi, the country’s largest and oldest brewery. Brarudi, the country’s largest taxpayer (with an estimated 68 billion Burundian francs, over 21 million US$, in taxes in 2024) announced last year that it was running out of malt, an essential raw material for the production of its beverages, due to a “lack of foreign currency”. And just like fuel, finding Brarudi beer now is like looking for a needle in a haystack. Once ‘everyman’s’ drink for decades, available even in the remotest corners of the country, it has become a luxury product that can only be found in the country’s major hotels. The state has taken on the difficult task of regulating its distribution, just as in the case of other products that are in short supply.

But ‘regulating distribution’ often means raiding as much of the product as possible and storing it for the ruling party elite. “What little fuel there is goes to the ruling party. The same is true for beer”, said a journalist interviewed during the elections campaign, adding: “In Bururi, in the south of the country, I went to a bar to buy a beer, very close to where the CNDD-FDD was holding a meeting. I was told that all the drinks available in the entire locality had been taken by the ruling party.”

“The country is becoming unliveable”

For the population, merely surviving has become a problem, says an analyst who requested anonymity: “Burundians are used to living on what little they have. This has never been a developed country with all the abundance that goes with it. But it is now becoming increasingly unliveable. There is no hope for the future. Not so long ago, it was inconceivable to see a man with grandchildren leaving his family behind and leaving the country, since Burundians are very attached to their families. But the fabric of family life is being torn apart. The regime has infiltrated everything, right down to the family unit. People are suffering, but they cannot talk about it, not even at home. Espionage has reached into households. Young people are fleeing the country in all directions”

School dropouts

The flight of youth is perhaps the most alarming trend for the future of this small East African country of 13 million inhabitants, 65 percent of whom are under the age of 25. Since the bloody crackdown on opposition to Pierre Nkurunziza’s third term a decade ago, the exodus has shown no sign of abating. Neighbouring capitals such as Kigali, Kampala, and Nairobi are teeming with young Burundians, including children. Last February, two local media outlets dedicated special editions to sounding the alarm over a historic school dropout rate of 70 percent, citing “more than 4,500 students” who abandoned their studies in just three months in Kayanza Province (northern Burundi) during the 2024–2025 school year. Many of these young people, including minors, have lost faith in what school can offer them: it is said that a membership card for the ruling party now holds more value than a diploma. Youngsters now wander as far afield as the rural hills of Kenya, often without legal papers, selling peanuts and doughnuts to passers-by.

One of them, when interviewed by Ukweli, explained that “This business at least allows us to send something to our families who live in unspeakable poverty in Burundi.” The young migrant claimed to be able to send at least 3,000 Kenyan shillings per month, more than 150,000 Burundian francs (about 23 US$, which is more than some Burundi civil servants’ monthly salary). Young girls, meanwhile, are sent to Arab countries via intermediary agencies, some of which are owned by officials from the ruling party.

Tens of thousands more young people from wealthier families have migrated to Europe via Serbia; Voice of America reported 20,000 such departures between January and October 2022.

The president promised one million francs for everyone

During the 2025 election campaign, President Evariste Ndayishimiye brought out the heavy artillery to try to convince crowds that he would end poverty. In a speech in Gitega on 15 May that year, he guaranteed “one million francs (now about US$150, though subject to rampant inflation) to every Burundian within two years” source. Whether Burundians believed, or still believe, him is doubtful. In 2020, when he assumed power, he had made a similar promise of “money in every pocket.”

This is an edited and updated version of a story by an exiled Burundian journalist. It was originally published by Afrique XXI.

Call to Action

ZAM believes that knowledge should be shared globally. Only by bringing multiple perspectives on a story is it possible to make accurate and informed decisions.

And that’s why we don’t have a paywall in place on our site. But we can’t do this without your valuable financial support. Donate to ZAM today and keep our platform free for all. Donate here.