Responsible sourcing of ‘conflict minerals’ from Eastern Congo remains a facade

Western consumers, regulations, and “fair” and “green” certification agencies and companies have sought to make mineral sourcing in the DRC more responsible. Yet as the conflict persists, “blood minerals” continue to mingle with green ambitions.

By the end of the decade, 70% of sales by Volkswagen, Europe’s largest car manufacturer, should no longer rely on fossil fuels: a win for a greener future. These electric cars, however, are packed with capacitors, transistors, and semiconductors that require metals such as tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold. Much of this is sourced from the DRC, where armed groups use these “conflict minerals” to finance their fighting.

The minerals, abbreviated as 3TG, are crucial to the EU’s energy transition, which has prompted grand plans for “strategic autonomy,” particularly from China. The recent deal with Rwanda has been met with widespread indignation, as minerals sold as ‘Rwandan’ are largely smuggled out of the DR Congo by the feared M23 rebel group, which maintains close ties with Rwanda.

Notorious smelters

Volkswagen claims to be invested in “responsible supply chains for future generations” and cites Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) assessments as evidence that it sources responsibly. Yet our investigation casts doubt on these assertions. We found that Volkswagen’s supply chain includes some of the world’s most notorious mineral smelters. Even certain certified smelters continue to import from eastern Congo and rely on previously discredited certification schemes without conducting additional checks.

Remarkably, Volkswagen offers the highest level of transparency among European carmakers. It is the only major European manufacturer to disclose the origins of its tin, tungsten, tantalum, and gold. VW’s openness has made this research possible, whereas Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Renault, and Stellantis (which manufactures Fiat, Peugeot, and Citroën, among others) provide no information whatsoever about the sources of these minerals.

The EU’s stricter rules haven’t changed anything on the ground

A recent report by the EU Commission confirms that the bloc’s stricter rules on minerals have not changed anything on the ground in Congo. Companies like Volkswagen, which do not import minerals directly, are not even required to comply. This raises the question: what are promises of responsible mineral sourcing really worth?

Horrific violence

In January 2025, the M23 rebels seized large parts of eastern Congo with horrific violence and overwhelming speed. The Rwandan-backed militia gained control of the cities of Goma and Bukavu, home to millions, after the Congolese army surrendered. Thousands of deaths, the execution of civilians, torture, and the displacement of millions followed.

At the time, Jerôme Laurent*, a Congolese civil activist in his fifties and a widower living with his mother and children, was at home in Goma with his family. They heard gunshots in the night. Bombs exploded all around. The power failed, and there was no water. They spent three days and nights without going outside, lying under the beds for most of that time. After a few days, when Laurent finally left the house, “There were bodies everywhere on the main street, in uniforms and in ordinary clothes,” he says. “I couldn’t imagine such barbarism. I never understood it.” Worrying about his children, he adds, “They will never forget this. Those wounds will be difficult to heal.”

“The children will never forget this”

Being an activist for responsible mining in the area, and seeing that M23 was now targeting civil society, he realised he too had to escape. (An investigation by Amnesty International would later accuse the rebel group of disappearing, murdering, and torturing civilians and activists.) Laurent left his family and fled abroad from where he now tells his story. His name has been changed for fear of repercussions against him, his family, and his colleagues.

Miners in the mud

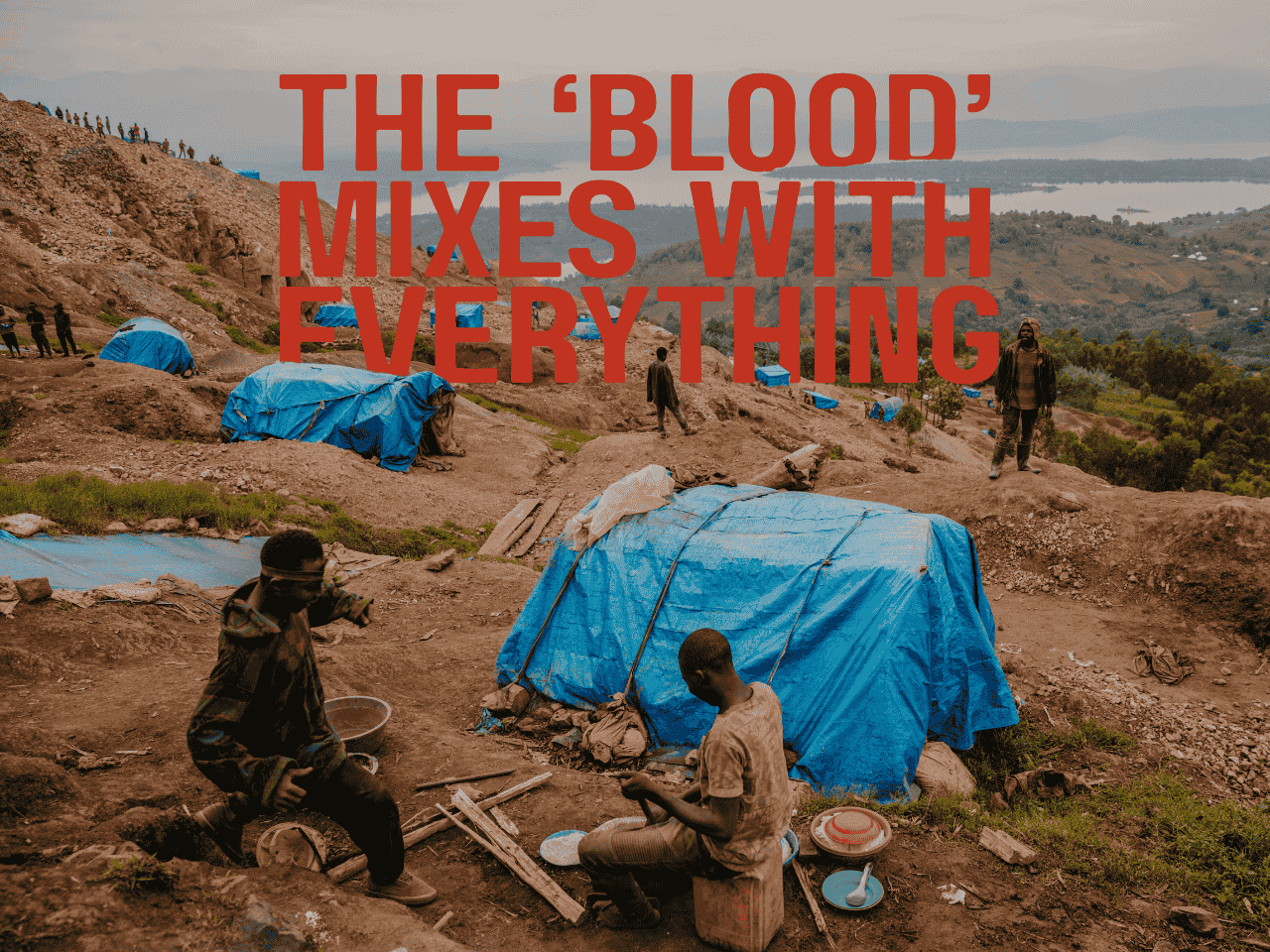

M23 controls the Rubaya coltan mining area, the largest in Central Africa, located some thirty kilometres from Goma. A recent BBC report documents the mining activities, where young men and women toil on barren, grey hills. Wearing rubber boots and clothes smeared with grey mud, they carry large sacks of ore on their shoulders. The creuseurs descend deep into hot, narrow shafts, working with little more than a shovel. Others sift through brown-grey mud pools with brightly coloured plastic buckets, searching for the black grit that sustains them: coltan ore, which contains tantalum, an essential component for capacitors in electronics.

The rebels impose “taxes” on those mining ore in the area. An additional tax is levied on allowing the minerals to pass to Rwanda, from where they enter the global market. According to UN experts, the rebel group earned approximately US$800,000 per month between May and October 2024 from illegal taxation at the Rubaya mine alone. These funds help them continue financing weapons and sustaining their control over the area.

The rebels impose taxes

Those working in the mine and selling to the rebels split hard rock with simple tools and no protective gear. They inhale toxic dust as they descend the improvised shafts, which frequently collapse, burying those inside. Last June, at least 21 people were killed in an accident. “At five o’clock in the morning, you can already see children aged six or seven working in the mines,” says Laurent. The working conditions were already harsh, but according to him, they have worsened since M23 arrived in full force. Laurent adds: “Some children are forced by their parents; others have no choice, as they have no family.” He apologises, almost in tears, when describing the miners’ living conditions. “At the end of the day, the children go home with 15 or 30 eurocents.”

A “tragic illusion”

The fact that smartphones and laptops are tied to war, human rights abuses, child labour, smuggling, and corruption has provoked outrage in the West for more than two decades. In response to international campaigns against the purchase of conflict minerals, the International Tin Supply Chain Initiative (ITSCI) was established in 2010 by the industry itself. It monitors mines and provides labels to local authorities, allowing minerals of a “clean” origin to be distinguished from those that finance conflict. ITSCI is now the largest organisation addressing conflict minerals in the Great Lakes region. When it arrived, Laurent eagerly participated in meetings with the government, the private sector, and ITSCI. “It came at a time when we really needed it.”

“As soon as the supply chain initiative started, I understood that it wasn’t working.”

But he soon became disappointed. “As soon as ITSCI started, I realised it wasn’t working.” Bags of minerals weren’t labelled at the mine, but in town, after they had been washed, dried, separated, and transported. “This meant that minerals from the red (conflict) zones could be labelled in the so-called green zones.”

Laurent’s observation has been echoed by numerous researchers and experts over the years. In his 2022 book Conflict Minerals Inc., Christoph Vogel argues that the hope that minerals in the DRC could be extracted in a way that does not finance war or conflict, through certification and careful sourcing, is a “tragic illusion.” While well-intentioned Western initiatives have consistently identified minerals as the cause and driver of ongoing violence in eastern Congo, Vogel contends that this perspective is far too simplistic. He rejects what he calls the “Orientalist Western” view, rooted in neo-colonial stereotypes, which continues to portray Central Africa as a dark place where warlords wage barbaric conflicts driven solely by greed.

Root causes

Instead, he says, minerals are a means to an end, not the other way around. The root causes of Congo’s war lie in a complex interplay of factors: the interests of politicians in Congo and neighbouring countries, conflicts between ethnic groups in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, territorial control, the legacy of colonialism, and a weak state. While initiatives such as ITSCI positioned themselves as white saviours, providing “conflict-free” materials, in practice, he argues, the benefits were largely for the companies, which could showcase their ethical credentials. Meanwhile, the war and suffering in Congo continued and, in some cases, worsened. For instance, according to a United Nations expert committee, minerals from the Rubaya mine were given ITSCI labels from a separate, legal mine while Rubaya was occupied by another armed group (the organisation denied the findings). After M23 arrived in Rubaya, ITSCI suspended its activities in the region.

Alex Kopp, researcher and campaigner at the non-profit organisation Global Witness, confirms that ITSCI functions as a “laundromat” that facilitates smuggling. In 2022, Kopp published a damning report which, he says, demonstrates that “throughout its existence, ITSCI has been used to launder large quantities of smuggled minerals, conflict minerals, and minerals mined by children, evidence from our research suggests.”

ITSCI acknowledges that its labels are sometimes used in smuggling. However, the organisation’s role is often misunderstood, according to programme manager Mickäel Daudin. “We don’t trace the minerals; that is the responsibility of local authorities. Nor are we the enforcers of action against fraud. Ultimately, companies themselves are fully responsible for their due diligence. We are there to support trade and mitigate risks.” He emphasises that significant progress has been made in recent years and rejects the perception of systematic failure. “Unfortunately, there is a false assumption that companies can know exactly where their minerals come from. That is not possible. There is no guarantee of conflict-free minerals.”

“Local authorities are involved in the fraud”

But how can a “certifier” like ITSCI rely on local authorities who, in a place like eastern Congo, are themselves parties to the conflict? “Indeed, the local authorities are involved in fraud. It’s no secret that the Congolese state is highly corrupt,” says Jerome Laurent. “ITSCI is a white elephant and a big lie. Its system exists only to give the appearance that everything is fine and to launder the minerals.”

Smelters use ITSCI and then have their purchasing procedures checked by independent audit firms. If everything is in order, the smelter is placed on a list of companies with “compliant status” by the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), an industry-led organisation. Volkswagen is a member of the RMI and uses the organisation as its standard for assessing 3TG minerals. The company expects its suppliers to have this assessment (or a comparable one, not mentioned by name).

The very worst smelters

However, more than a third of the 344 entities that supplied 3TG to Volkswagen in 2024 did not undergo an RMI assessment. Among those not assessed are notorious companies such as the African Gold Refinery in Uganda, the Gasabo smelter in Rwanda, the Sudanese Gold Refinery in Khartoum, and Kaloti in Dubai. Gasabo was sanctioned by the EU earlier this year for illegally importing conflict gold from the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Sudanese refinery was owned by the paramilitary RSF group, widely accused of committing genocide in the country’s bloody war. “This is astonishing to see,” says Marc Ummel, commodities expert at the Swiss organisation SwissAid. “Volkswagen has some of the world’s worst, most notorious smelters in its supply chain.”

A “compliant” RMI assessment carries little significance. The forms amount to little more than a completed questionnaire with a stamp. They provide no information about the minerals’ origins, leaving independent researchers, activists, journalists, or consumers unable to verify where the metal actually comes from. RMI’s suspension of its collaboration with the ITSCI system in 2022, reportedly “because ITSCI no longer met its requirements,” proved to be largely ceremonial. Today, RMI merely requests additional documents such as supplier information, supply chain risk assessments, and mine visit evaluations, but these are seldom made publicly available.

In practice, Volkswagen suppliers continue to use the discredited system, yet have nonetheless received the RMI’s green stamp. Kazakh smelter Ulba, Malaysia Smelting Corporation (MSC) and Thaisarco in Thailand, all accused by Global Witness of purchasing Congolese conflict minerals, still display such endorsements. In 2024, the Malaysian tin smelter stated that it “continues to make full use of the proven ITSCI process.” Ulba, which fully employs ITSCI, recorded no fewer than 117 “high-risk incidents” from Congolese conflict zones in 2023–2024, yet continued to source from the same suppliers. Despite this, Ulba was listed as an “RMI-conformant” smelter.

“Many companies look no further than a certificate”

In response to accusations that the RMI operates as little more than a façade of ‘responsible sourcing’, the organisation states that it does not conduct “material validation assessments.” In other words, it does not guarantee that the minerals are “conflict-free.” “Many companies look no further than a certificate,” says Andrew Britton, director of Kumi Consulting, which evaluates organisations such as the RMI for the European Commission. “Companies are responsible for their own due diligence; they should not outsource it. But that’s exactly what happens. And that’s a big problem.”

Cycle of violence and conflict

The DRC government blames Western companies for perpetuating the cycle of violence and conflict. In December 2024, it announced that it was filing a complaint against the electronics manufacturer Apple in Belgium and France, accusing the company of using “looted” and “laundered” minerals and of concealing this from consumers. According to the Congolese state, Apple is therefore co-responsible for the “unimaginable damage and suffering” caused.

The DRC government blames Western companies

Apple used ITSCI, and the complaint is primarily based on the Global Witness investigation mentioned above. The smelters MSC and Thaisarco, which supplied both Apple and Volkswagen, are also implicated in the complaint.

Apple denied the allegations, and French authorities dismissed the case for lack of sufficient evidence. Belgian authorities, however, appointed an investigating judge, signalling that they are treating the complaint seriously. The law firm representing Congo described the complaint against Apple as a “first salvo,” suggesting that further actions may follow, aimed at compelling companies to take greater responsibility for their supply chains.

In the hot seat

Apple may currently be the only major company facing charges, but Volkswagen and others buy from the same suppliers, even from smelters that Apple dropped. “Companies like Volkswagen really need to do better,” says policy analyst Sasha Lezhnev of research institute The Sentry. “The car industry isn’t paying attention, especially with the evidence about M23’s control over the mines that now comes forward.”

Volkswagen declined an interview request and refused to answer specific written questions, providing only a written statement asserting that the company has no direct relationship with the smelters mentioned and that, due to the complexity of its supply chain, it could not confirm or deny purchasing from them. A spokesperson added that the company aims to source exclusively from RMI-approved smelters in the future, despite the fact that the proportion of such smelters in its supply chain has actually declined in recent years.

The response fails to convince Marc Ummel of SwissAid (one of the organisations advocating for traceable supply chains). “Of course, Volkswagen’s supply chain is complex. But they are clearly not taking it seriously. If Apple can drop smelters, so can Volkswagen.” Marianne Moor of the peace organisation Pax insists the company should disclose to the public exactly which mines supply their raw materials. “They cannot just point the finger at their suppliers; they must also demand transparency from them.”

Not buying from the region could make the situation even worse

Would the only solution be to stop buying from the region altogether? Apple recently announced exactly that: it would cease purchases from the DRC and Rwanda. But activists, including Jerome Laurent, as well as academics and ITSCI itself, warn that this could make the situation even worse.

The ongoing displacement of citizens in eastern Congo means that mining remains one of the few stable sources of income. Companies that cease purchasing Congolese minerals are depriving people of what little income they have. Economists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison showed that child mortality rose significantly in areas where trade halted following the introduction of American legislation, possibly because mothers could no longer afford healthcare for their children.

Pax’s Moor believes that companies should nonetheless stop sourcing from eastern Congo and Rwanda. “It’s a dilemma, of course. But if we continue sourcing from eastern Congo, we will continue to finance armed groups through mining. And then the war will continue.” Daudin of ITSCI takes a different view. “If companies only buy conflict-free minerals, there would be no purchasing from this region at all. That is the opposite of responsible purchasing. The goal is to avoid disengaging from the problems.”

Political pressure

Rather than disengage, the West should apply political pressure on the Congolese and Rwandan governments, argue experts from the Egmont Institute and the University of Antwerp. At present, the EU’s deal to channel Congolese minerals through Rwanda reveals little more than double standards, says Congolese gynaecologist and human rights activist Denis Mukwege in a statement. Mukwege, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018 for his work against weaponised sexual violence during the ongoing war, added that after the new M23 offensive, the Rwanda deal was put under review but not suspended.

“We want to return home so that everyone can go about their business”

To Jerôme Laurent, the most pressing issue is peace. He believes that the Congolese should be able to sell their minerals fairly and hopes that the recent peace deal between Rwanda and the DRC, brokered by the United States, will bring some relief. “But I doubt it has actually been properly discussed,” he says. Critics argue that the US appears primarily interested in Congo’s minerals, while M23 is not involved in the deal at all. “We don’t need more war,” Laurent insists. “We want to return home, so that everyone can go about their own business.”

This article was published with support from Journalismfund Europe.

Call to Action

Working towards a new relationship of equality between Africa and Europe, ZAM platforms African investigation, activism and creativity that challenges exploitation, white supremacy and the erosion of democratic rights. Donate here.