Breaking up the family

In the past decade, judges in Nigeria have been captured by political power, a situation that has been linked to violent criminality and conflict in the country. However, against great odds, some brave legal minds are fighting to restore the rule of law.

When law professor Chidi Anselm Odinkalu started receiving serious death threats, he understood that he had been stepping on powerful toes. Odinkalu (now 57), who, as a former head of the Nigerian Human Rights Commission, had relied on the integrity of the judiciary in his country to address human rights violations, had noted a dangerous slide away from such integrity after 2016. On the night of 8 October that year, the Department of State Service (DSS), Nigeria’s powerful secret police, raided the residences of 15 judges in six Nigerian states on suspicions of ‘corruption’.

Politics and grudges

The case turned out to be a scam, or in the words of the National Judicial Council (NJC), “a denigration of the entire judiciary as an institution.” The NJC said that the DSS’s claim that the Council itself had sent in a complaint about the fifteen judges was untrue: it had only reported two of the fifteen, and these two had been disciplined. The case was later also dismissed for lack of evidence by the court.

Several affected judges then publicly stated their suspicions that the raid had been either motivated politically or by grudges held by the DSS. One said it was possible he had been included in the raid because he had berated the DSS in open court over a matter of unlawful detention. Another had ruled in favour of an opposition party. A third had, based on human rights concerns, granted bail to a separatist leader as well as to a former National Security Adviser who had been kept in DSS custody for more than a year without being charged with anything. A fourth had, about a decade previously, ordered the arrest and detention for professional misconduct of a lawyer who, at the time of the raid, had become the Minister of Justice.

The raid was called “a denigration of the entire judiciary”

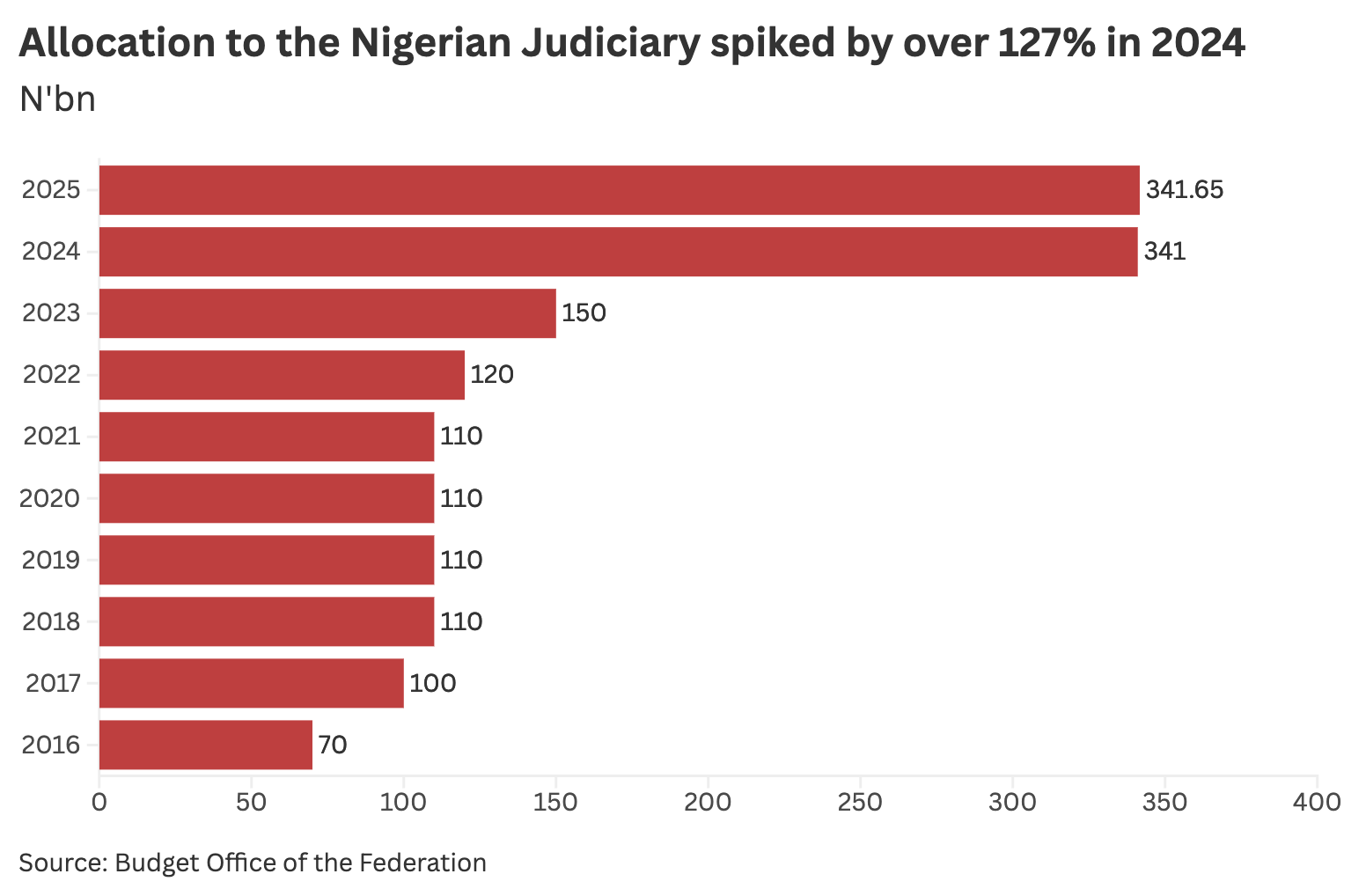

Whatever might have prompted the DSS raid in 2016, it had a chilling effect. Professor Odinkalu, who had left the NHRC in the same year, recalls it as an “act carried out to intimidate the judiciary,” adding, “you could see a manifest recalibration of the judicial psyche thereafter.” He noted a pattern starting to emerge in two ways: first, increased intermingling between judges and powerful politicians, including reciprocal gifts and favours (see box), and second, an increase in rulings that favoured the powers-that-be and covered up human rights violations.

Starting to resist

Advising international human rights organisations as well as Nigerian civil society in the three years after leaving his NHRC post, it was in 2019 that Odinkalu took it upon himself to speak out about what was happening, which he did through the media. “Somebody had to say something. You got to the point where, in 2019, there was no governorship election in Rivers State, because a state governor or a ruling party in a state procured a judge to give an order that the most competitive candidate should not compete. The people then did not have a choice (for another candidate).”

A judge’s son was suddenly a political candidate

The examples kept mounting. This politician was doing a favour for that judge. Another judge’s son was suddenly at the top of the list of state candidates for the ruling political party. Amid civil society outrage, judges were given cars and houses by the Mayor of Nigeria’s capital, Abuja. A former President of the Court of Appeal used her position to ‘help’ several senators cross legal hurdles to Senate seats. A ruling party candidate lost, but the Supreme Court validated his fraudulent election. The list went on and on.

Vilification of him on social media and death threats began after Odinkalu publicly confronted violations of Nigeria’s law and constitution, and condemned the often literal family ties between politicians and the judiciary through media articles, press interviews, and appearances at civil society events. “We have seen a capture of the judiciary by a narrow political elite,” he says. “It’s like a joint enterprise of the politicians and the judiciary. Judges need politicians to keep them in power; politicians need the judges to rewrite the rules to keep them in office and plunder our resources.”

The mingling

- In 2019, the husband of Zainab Adamu Bulkachuwa, former President of the Court of Appeal, was elected as a Senator through one of Nigeria’s major political parties, the APC. In the same year, their son, Aliyu Abubakar, was nominated as the governorship candidate for Gombe State.

- In 2020, Nyesom Wike, then Governor of Rivers State, presented 24 houses and 41 SUV vehicles to judges in the state. Earlier, he had already donated 29 Renault Koleos SUVs to judges of the Customary Court. At that time, his wife, Eberechi Suzette, was serving as a judge in the same state.

- Before that time, Wike had already given 35 Ford Explorers to some judges in Rivers State.

- In January 2021, Simon Lalong, then Governor of Plateau State, appointed the daughter of the President of the Court of Appeal as a judge of the state's High Court. When Lalong lost the senatorial election in 2023, the Court of Appeal overturned the opposition party's victory and declared Lalong the winner.

- In 2022, Bayelsa State Governor Douye Diri appointed his wife to the position of judge on the state High Court.

- The two sons of former Nigerian Chief Justice Mohammed Tanko were nominated for seats in the National Assembly by Nigeria’s two main political parties in May 2022.

- In 2024, Eberechi Suzette, wife of Nyesom Wike (now Mayor of Abuja), was promoted from her position as a judge at the Rivers High Court to the Court of Appeal. Several months later, Wike used federal funds to gift two dozen houses and cars to judges in Abuja.

- Nyesom Wike’s sister-in-law, Lesley Nkesi Belema Wike, was appointed a judge of the Federal High Court in the same year.

Extrajudicial killings

Things had not been all well even before 2016, when Chidi Odinkalu was still the chair of the National Human Rights Commission. But he had then felt there was still space to take on the DSS and other abusive arms of state. For example, under his chairmanship, the NHRC had investigated the killing of eight individuals and the wounding of eleven others in a building under construction in Abuja in 2013. The authorities had claimed that the victims had been members of the violent insurgents' movement, Boko Haram, but they had provided no evidence for this. Odinkalu’s NHRC had discovered that the victims were simply drivers of tricycles, artisans, hawkers, and traders who could not afford to pay the exploitative and unaffordable house rents in the city. Thousands of unskilled labourers typically occupy uncompleted buildings in Abuja.

The owner of the building where the killings took place, a retired military officer, had asked the agency to empty the place for him after he had been unable to get the hawkers to move out through "verbal appeals." The men from the DSS had then invaded the building and shot them. The state had been forced by the NHRC to award compensation to the victims' families.

The authorities had been even more perturbed when Odinkalu’s commission had probed extrajudicial killings by the Nigerian police, who had dumped unidentified corpses at hospital morgues. The victims, labelled as armed robbers, had in reality been unfortunate individuals from the streets, whom the police had targeted for extortion and bribes; those killed had mainly failed to raise the bribe money. (The extrajudicial killings were later to lead to the mass protests in Nigeria in 2020, called the #EndSARS movement. The police squad in question was called the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, SARS.)

Up until 2016, many judges had generally been brave enough to sanction such practices. But this was no longer the case.

Many want change “but who will bell the cat?”

Now a lecturer at Tufts University, Medford, USA—a position he took up in 2021—Odinkalu collects notes sent to him by whistleblowers from within the Nigerian judiciary. For, he says, there are many who share his concerns, but addressing them directly would be risky. “When the people discovered that I was consistent, those in the judiciary started sending materials to me, soliciting that I should address the issues. In many cases, they provided documents, which I verified. Most of the documents came from those who want the system to change. The sources were from every level of the judicial system and hierarchy. A lot of people would like to see things changed, but who will bell the cat?” Through this foreign detour, Odinkalu now uses the discoveries sent to him to write his op-eds, present in online talk shows, and speak at regional and civil society events during (mostly unannounced) visits.

A Supreme Court Justice takes on the networks

In an online clip that was widely circulated in 2024, Nigerians saw and heard retired Supreme Court Justice Amina Augie reveal unbelievable examples of Nigeria’s corrupted court systems. In what was supposed to have been a run-of-the-mill panel discussion in Lagos, Justice Augie, in her trademark smiling and soft-spoken way, exposed cases of decades-old nests of corrupt staff in the courts, saying that these clusters amass wealth through illicit means and wield power simply through adding or cutting through red tape, whichever is the most profitable. She explained that even heads of administration have been powerless because, even if authorities had long identified the culprits, they could not act against their influential (often political) backers. Augie also shared her experiences in ordering the reassignment of several officials and breaking entrenched networks, adding that she had received many threats in response. Listen to the clip here.

While Chidi Odinkalu was belling the cat from his new base in the United States, another legal mind had come to the fore in Nigeria, fighting for the rule of law. Senior Advocate Jibrin Samuel Okutepa began his journey as a car mechanic, then put himself through a commercial college to qualify as a typist. He later worked as a fireman with the Nigerian Fire Service in Benue State before finally enrolling in an undergraduate Law degree at the University of Jos in Plateau State. He quickly became known as a human rights lawyer when, in 1995, he took on a case to confront the brutal military authorities in Benue State. The case involved defending 37 students and some lecturers who had been expelled from Benue State University after protesting the military government's years of non-payment of students’ bursaries.

The protests had included barricading the main road in the capital. A group of students had also stopped a military officer and punctured his vehicle’s tyre. The military governor of the state then decreed the expulsion of all those found to have been involved. Even some university lecturers who had attempted to dissuade the students from violence were penalised.

The students won their case

Okutepa had agreed to defend those expelled pro bono after prominent lawyers in the country, afraid of the then military government’s dreaded and wide-ranging arbitrary powers, refused to do so. He filed a case against the expulsions, defeated the government’s lawyers, and secured a repeat victory after the state appealed. The authorities then had no choice but to set up a panel to review the expulsion and, upon the panel’s recommendation, allow them back.

Challenging loopholes

It opened the floodgate of similar briefs for him in years to come. In the last decade, Okutepa has challenged the (mis)application of the Nigerian Electoral Law in Nigerian courts in cases where authorities used certain interpretations to secure wins. Among these was an amendment to the Electoral Law and the Constitution to state that if a governorship candidate dies in an ongoing election, their running mate shall inherit the votes. This was important because, just previously in Kogi State, authorities had picked a favoured aspirant—who had lost in the primary election in 2015—to inherit the votes of the leading candidate who died during vote counting.

Another likely win for Okutepa, recently, has been a proposed amendment to the Electoral Act 2022 to expressly recognise the electronic process in future Nigerian elections. Okutepa has fought at election tribunals, the Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court to fault rulings that had accepted handwritten election results over actual data captured by voting machines. These rulings had confirmed fraudulent wins by politicians who had themselves written in voting figures, even when these exceeded the total number of voters in a certain area.

Judges’ rulings had sanctioned cheating

Based on Okutepa’s challenges, both the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and pro-democracy groups have now called for an amendment of the law. Barring any unforeseen developments, it is expected that the Electoral Act may be amended to reflect the lawyer’s argument.

A long and hard road

Legal challenges can only go so far. When political power was directly challenged in Kogi State in 2023, and the incumbent governor’s party had secured its win through massive vote dumping and manipulation, as well as violence against opposition supporters, new efforts by Okutepa failed. Despite providing documentary and digital evidence and appealing all the way to the Supreme Court, the incumbent was confirmed. In the same Kogi State, in 2019, the leader of the women’s wing of an opposition party was burnt alive at her residence for resisting electoral fraud. The case went to court, but only one of her killers was jailed. Several others, who claimed to belong to the governor’s political party, escaped justice.

Okutepa understands that the journey to restore the rule of law and justice in Nigeria will be long and arduous, as long as “to become a judge, you must have recommendations from one politician or the other (and then) you will be directed to do whatever the person who helped you wants you to do. Until there is an independent process of recruitment, the judiciary will continue to decline,” he says. “Our hope lies in an independent judiciary that pronounces consequences for political misbehaviour and rule against it irrespective of who is God.”

A wife’s fraudulent appointment was stopped

Which is why he and several colleagues, in 2024, fought hard against the fraudulent appointment of the spouse of a former governor of Kogi State as a judge. It resulted in another win: after their intervention, the Nigerian Judicial Council, normally extremely reluctant to act against erring judges, removed the governor’s wife from the list of appointees. This caught the attention of Professor Odinkalu, based in the US. “I would like to thank the Senior Advocates of #Nigeria from Kogi State, including Yunus Ustaz [a human rights activist] & @jibrinSAN, for #TakingAStand on this abuse of judicial appointments. It’s about time,” he wrote on X.

An “oasis of truth”

Odinkalu’s volleys have, in the last few years, amassed quite a following among Nigeria’s civil society and the legal profession itself. When the Mayor, who had been exposed by Odinkalu for allocating free houses to judges, called on the statutory bench of lawyers to penalise the professor for “degrading the legal profession,” many came to his defence. A senior lawyer, Ikeazor Ajovi Akaraiwe, described Odinkalu as “an oasis of truth and courage among cowardice and self-preservation… If anyone has degraded the legal profession, it is certainly not Chidi (Odinkalu). Look at yourself in the mirror and see who should be hauled before the disciplinary committee.” Amnesty International also supported Odinkalu, condemning the Abuja Mayor for his “harassment and intimidation”.

Says Odinkalu: “The only way to fight is to recruit a critical mass of enlightened citizens. I do not suffer the illusion that I alone can accomplish this recruitment, but I am hopeful that part of the material I provide can help in that process.” Okutepa, too, doesn’t see himself giving up the fight, especially since the “judiciary capture,” in his view, also contributes to the violent conflict and insecurity in the country, which is wracked by both criminal syndicates and violent insurgency. “Where there is injustice, there will be insecurity; we are witnessing insecurity in Africa because of injustice in diverse ways.”

We need to “recruit a critical mass of enlightened citizens”

Meanwhile, the paths of the two continue to intersect. When Okutepa stressed that judges in Nigeria need to free themselves from those who influence them, Odinkalu shared the statement on his X (formerly Twitter), writing: "Thank you, Okutepa."

See all the instalments in this Transnational Investigation here

Legal Rebels | Cameroon, Uganda, Nigeria, Malawi & Ghana

Cameroon | A new alliance

Malawi | Naming and shaming

Uganda | Radical rudeness

Ghana | Smaller and bigger victories

Call to Action

ZAM believes that knowledge should be shared globally. Only by bringing multiple perspectives on a story is it possible to make accurate and informed decisions.

And that’s why we don’t have a paywall in place on our site. But we can’t do this without your valuable financial support. Donate to ZAM today and keep our platform free for all. Donate here.