Inside the Brain Drain Destroying Zimbabwe's Health System

After Zimbabwe reached independence in 1980 the state introduced free health care for citizens, with new clinics and immunisation available countrywide. But then training of doctors and upkeep of hospitals stalled, and three decades of neoliberal reforms and widespread corruption, in concert with sanctions targeting the ruling ZANU-PF party, have left the health system ravaged. Now many medical workers are voting with their feet. Zimbabwe’s most valuable export commodity may be its gold, but its healthcare workers are leaving the country too.

Zimbabwe, the last African country to gain independence from British colonial rule in 1980, now sees its doctors and nurses leaving the country almost as fast as its gold. Every year an estimated US$1.5billion worth of the precious metal leaves the country through illegal routes, while the state budgets less than half that for healthcare. Inflation remains in the triple digits, and health workers cannot live on the wages they are paid. Even those who are willing to suffer poverty often simply cannot do their jobs amid the persistent shortages of medication and broken equipment they must cope with in dilapidated hospitals. But their skills are in increasing demand overseas, including in Britain, whose government health service actively recruits anglophone Zimbabwean health workers. Over 2,200 left Zimbabwe in 2021 alone, with 900 of these being nurses. This was twice the number that left in 2020 and triple that of 2019.

First freed

Zimbabwe gained independence in 1980 after a protracted liberation war. In the new republic, health care was made free to those earning under a certain minimum. Clinics that had been destroyed in the war were rehabilitated and upgraded, and new health centres were built and facilities were opened to all. By 1981 Zimbabwe had rolled out immunisation for children and pregnant women and, combined with water-borne disease control programs, infant mortality was reducing dramatically.

These were huge improvements in a country that, before independence, had close to ten times more doctors for its white population (roughly one per 830) than for black citizens (one per 8000), and that had previously reserved two out of its four national referral hospitals for its tiny minority white population, while the entire black population of seven million were expected to manage with the other two. Liberation meant a black citizen could now go to any hospital or clinic to be treated, and everybody including the emerging elite trusted the healthcare system. Even Sally Mugabe, former president Robert Mugabe’s first wife, received extensive treatment for kidney failure at a local hospital in the early ’90s.

A black citizen could now go to any hospital to be treated

Nurse Diana Svorai (69) remembers being passionate about her job. ‘When I graduated as a nurse in 1984, it was a noble profession to work in hospitals and save lives.’ In the two urban hospitals where she worked in Harare the conditions were good, she says. ‘We could afford to do most of the basic things from our salaries, including building a house. We got full support from the government in terms of medicines and equipment.’

However the government’s initial investments and recruitments soon stalled. Former member of parliament Collen Gwiyo, whose constituency would later be hit hard by a cholera epidemic made worse by dilapidated healthcare systems, recalls the first hiccups. ‘We had adopted infrastructure that had been previously tailored for a small number of people - the white few - but staffing, in terms of having adequate experts, was still an issue’. The system coped for the first ten years, he says, by ‘drawing from the facilities that were already there’.

Austerity

Beginning in 1991, under pressure from neoliberal development partners such as the International Monetary Fund, Zimbabwe launched what was called its ‘Economic Structural Adjustment Programme’ (ESAP).

At its core ESAP meant reducing government spending with the aim of opening the economy up to private sector competition. Healthcare services, which were already feeling the strain caused by the sudden widening of access, now also had less money to spend for infrastructure, operations and new staff training. The changes led to the ending of free medical care and other health subsidies. Meanwhile companies who had supplied state services lost business, resulting in losses of income for many workers and their families. By 1993 the Zimbabwe dollar was worth a fraction of its former value and the country’s health budget had shrunk to US$58 million - a historic low.

Zimbabwe’s elite was suddenly 'disabled'

After some years of recovery, a new assault began in 1997 when politically-connected individuals started claiming disability compensation through the War Victims Compensation Fund. These large payouts, from a fund which was meant to support veterans injured in the independence war, caused widespread outrage and led to a judicial enquiry as well as to international headlines such as ‘Zimbabwe’s elite polish their stumps.’ (2) Outrage by real veterans soon prompted the government to announce an unplanned welfare payout for all veterans, costing the equivalent of US$320million.

Such a large cash injection created economic havoc. The local currency crashed again, creating an economic meltdown, and the day of the payouts themselves, November 14th 1997, is remembered as Black Friday. Doctors and nurses, whose poor wages and working conditions had already driven them to several strikes since the early nineties, again took to the streets.

A war for powerful families

The by-now wildly fluctuating state budget would take another hammering a little over a year later, as Zimbabwe sent troops to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to assist then-president Laurent Kabila, who was under siege from rebels. The official justification was the assistance of a fellow liberation leader but the incursion also allowed powerful Zimbabweans to establish new business ties with the mineral-rich nation. A reported 10,000 troops were deployed to DRC at a cost of about US$3million a month, drawing vehement criticism both externally and internally. An editorial in the Zimbabwean 'Financial Gazette' at the time asked: ‘If the government has money to deploy troops, tanks and jets in faraway Congo for 14 months - the cost of the expedition is US$42 million using the government's own figures - why can't it find the money to pay long-suffering doctors, whose plight has forced them on the streets for the fourth time in 10 years?’

'The government can deploy troops and tanks, but cannot pay doctors'

Going private

When Enock Choto qualified as a nurse in 2001 the working conditions were tolerable, partly thanks to increased support from the private sector. ‘We still got free food and accommodation. There was a vehicle loan fund. Most companies also donated towards the welfare of health workers’, he says. But Western sanctions against the state, levied in response to Zimbabwe’s participation in the war in the DRC as well as to its land reform programme that had confiscated land from white farmers, were beginning to bite the public sector. Ironically an unintended consequence of these sanctions would be to gradually exclude reputable international companies from the country’s economy, leaving the mining sector open for countries less publicly concerned with human rights issues, such as Russia and China. This would eventually open the floodgates of rapacious and illegal export of gold and diamonds, which then drained state budgets, ultimately again impacting on services such as healthcare.

Private clinics overtaking the public sector would then ‘make the public facilities derelict’, recalls Choto. ‘Better pay in the private sector would cause some health workers to abandon their public jobs, to the point where a health worker dividing his time between a public facility and a private clinic would damage a public machine to make money at the private clinic. And government health workers would only go to government facilities to scout for well-to-do, desperate patients to convert to private patients.’ Tendai Tafa, a nurse working at a private hospital, describes how ‘rich people and politicians with cancer’ would flock to her work place and even call her at home, to access treatment that the public sector wasn’t offering. ‘They also started flying out of the country to get healthcare’, she adds.

Jevas Tvarai, who qualified as a registered nurse in 2003, became frustrated after working for three years at a local public hospital. ‘The mortuary could be down for months, which enabled private players to come into play, but they charged higher prices. Patients were forced to pay extra to get assistance at the hospital. People were made to buy medicines at private pharmacies.’ Beginning in 2006 Tvarai began to offer medical care to people in his community for a nominal fee. ‘In my area, many are low-income earners and the majority lack medical insurance. When they get sick and visit public hospitals there are no medicines, while private health care is very expensive.’

Cholera

In 2008 cholera hit the country, killing 4000 Zimbabweans. Collen Gwiyo, whose constituency of Chitungwiza was one of the most severely affected, explains how the disease resulted directly from reduced investment in infrastructure. ‘The provision of [piped] water for every Zimbabwean is still a dream. In the first 10 years of independence it was okay, we had enough water and we could water our gardens. But in the second ten years, due to narrow infrastructure, we began to experience water rationing. When that happens, the flow of the sewer is also affected and the drainage system gets damaged because water is not moving frequently. When there is rain, some of the clogged drainage bursts and overflows and you experience waterborne disease outbreaks.’ In short, pipes left to rust because of lack of maintenance and budget cuts caused cholera to spread, and it became an epidemic because the healthcare system was unable to cope.

In an article titled The politicisation of health in Zimbabwe: the case of the cholera epidemic 2008-2009, historian and lecturer Dr Clement Masakure describes the government’s incapacity to act when the cholera hit. He points to a temporary improvement beginning in 2009 when the opposition Movement for Democratic Change party won in elections and a Government of National Unity (GNU) came to power. In an as-yet unpublished paper Masakure further describes how under the GNU, which lasted until 2013, ‘social service provision improved as the government successfully used (a) targeted approach to public sector investment, including hospitals.’

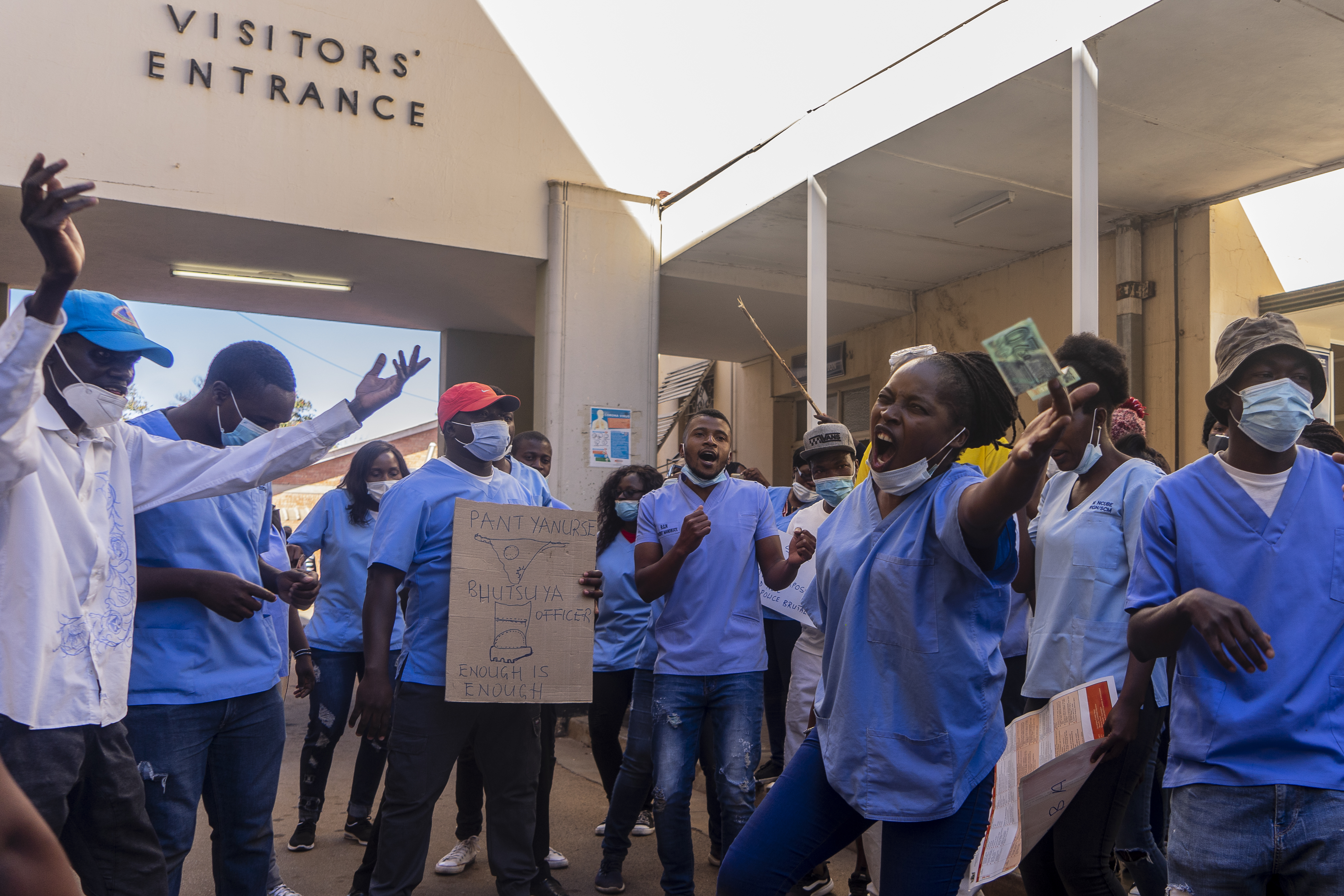

After the end of the GNU however, the health budget dropped again and nurses’ positions were again frozen, prompting many in a profession already suffering from mass emigration to look for greener pastures. Masakure’s paper also describes how, five years later, thousands of striking nurses were fired when the government deemed their actions to have been ‘political’.

Resource plunder

The budget cuts in 2013 may have been partly motivated by a sudden precipitous drop in tax revenue from the mining sector during the GNU era. Income from Zimbabwe’s staggeringly productive diamond industry essentially stopped reaching the state, with the finance minister, Tendai Biti, complaining bitterly that those in charge of the state’s partnerships with foreign mining companies were simply selling diamonds directly, without paying tax. After the collapse of the GNU in 2013 Biti went on record to claim that ‘the regime’ - now ZANU-PF once again – was turning a blind eye to illegality in the quest for foreign currency ‘from gold mining’. In 2013 Zimbabwe’s Minerals Marketing Corporation reported that the country was losing US$50 million to gold smuggling every month. In 2016 President Mugabe himself admitted that an estimated US$15 billion worth of diamonds had been looted.

2016 was the same year that it was reported that Mugabe, by then 92 years old and with failing health, had spent US$53 million on foreign trips, including to Singapore, where he was receiving medical treatment. According to the AsiaByAfrica website, which investigated Mugabe’s connection to Singapore, that was more than double the amount Zimbabwe invested in its hospitals and health centres that year.

Former MP Collen Gwiyo offers a simple solution. ‘If the government had to say, all mined diamonds and gold should be deposited with the Ministry of Finance or the Reserve Bank, we can raise enough revenue to rejig all government hospitals within a year and you can see results after five years.’ But there seems to be little hope of that. While almost half of Zimbabwe’s population remains in abject poverty, the children of the wealthy flaunt their lifestyles on social media.

Daily avoidable death

Forty years after independence there is still only one medical school in Zimbabwe, and the country continues to haemorrhage doctors and nurses. Those who choose to remain face a near-impossible task. ‘We are losing a lot of lives’, says nurse Tvarai. ‘Broken equipment is not repaired. Even small machines to check blood pressure, which are cheap, are in short supply.’ When some repairs do get done, he adds, the companies contracted and paid from the health budget to do these are doing ‘shoddy jobs’. Meanwhile NatPharm, a state-owned enterprise mandated to procure, store and distribute medicines and medical supplies for public health institutions, recently saw its directors fired over a scam involving procurement of COVID-19 medicines and equipment.

Amid shortages, understaffing and broken equipment, and faced with ever-decreasing wages relative to inflation, more and more health professionals have started charging patients. ‘Patients are told there are no medicines even when there are’, says Tvarai, ‘so that they must pay to get them’. He adds that he has seen women in labour left without care until they pay, perhaps a reason why backstreet maternity clinics have mushroomed recently. To avoid extra costs, patients now routinely bypass hospitals and go straight to pharmacies to purchase what they think they need, or buy unregistered medicines from ‘street doctors’. Tvarai nevertheless continues to try help patients as best as he can. ‘I charge cheaper prices. My job is a calling and not necessarily to make money. I do home visits to attend to patients who cannot afford to go to hospitals.’

Doctor Mthabisi Anele Bhebhe, the Government Medical Officer at the Plumtree District Hospital, located close to the Botswana border, likewise continues to swim upstream. He has ‘never experienced the beauty of working in a fully equipped hospital in Zimbabwe’, he says, adding that he would like to see ‘robust academic and media coverage investigating what was done right before, and what eventually went wrong. … It’s hard to (judge) the performance of the health system in Zimbabwe over different time frames, due to the inadequacy of published literature. But generally, the public health system has gradually and dramatically deteriorated over the last two decades. The quality of the infrastructure, transport system and hospital equipment has declined due to neglect and poor maintenance. We are improvising with what was left before independence.’

'We are improvising with what was left before independence’

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Zimbabwe’s 2021 maternal mortality rate stands at 614 deaths per 100,000 live births, one of the highest worldwide. Donor-funded programs focusing on malaria, HIV and other diseases cost over US$400 million per year. Over the five years up to 2020, development partners contributed 65% of total actual health spending in Zimbabwe, while the state health budget contributed only 35%. Britain is the third largest donor, but 63% of emigrating Zimbabwean health workers end up in the UK.

A luxury vehicle

Zimbabwe recently announced that it will go to the UN to seek compensation for the cost of its exodus of doctors and nurses, saying that it has lost millions of dollars in costs for the training of health workers who have then been poached by other, often wealthier nations. But even if the UN agrees and compensation is awarded, it seems unlikely that the general situation would improve unless there are changes in state policies and management. A video clip circulating online shows a member of Zimbabwe’s state Health Board driving in a luxury vehicle past doctors striking in protest at wages of $275/month.

Meanwhile, the gold continues to flow out, too. In 2020 Henrietta Rushwaya, president of the Zimbabwe Miners Federation, was briefly arrested at Harare airport while attempting to smuggle six kilograms of gold out of the country to Dubai. Reports that she is President Mnangagwa’s niece have been denied, but Rushwaya remains miraculously free on bail, as does her former driver, who was caught at OR Tambo International Airport in South Africa with gold worth US$730,000 seven months later.

Except for Dr Bhebhe at the Plumtree District Hospital, all health workers interviewed in this article have had their names changed for safety reasons. The name of the author has also been changed.

The author also notes their personal interest in the story, having lost their mother during the cholera epidemic of 2008.

The Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and the ruling party, ZANU PF were asked to comment but had not done so by time of going to press.