Shakeera Baker doesn’t like asking for help to put food on the table for herself and her two children, but she struggled to make ends meet in mid-2020 already. And then the COVID lockdown prevented her from even going to look for work. So she and her equally unemployed husband applied for the new COVID 19 grant.1 At 350 Rands, US$ 20, per month, it wasn’t going to be much. It barely buys you some electricity, some bread, some tea, cooking oil, rice, some vegetables. But it was something. Only they never received it. ‘I tried phoning SASSA but their number doesn't work’, she says.

It was not surprising. At the time, SASSA, the South African Social Security Agency tasked to distribute the social relief grant, was receiving three thousand calls an hour. As a 2020 study on the South African lockdowns would state a little later, close to half of households, reported having run out of food already in April that year.2 And many of the hungry were phoning the agency that had been tasked to help.

SASSA had been told by government to do this, but was barely ready. Its CEO Busisiwe Memela would later write3 that ‘it requires four to six weeks to make any changes’ to the grants payroll as it is, and now close to ten million new applicants had to be processed ‘within two weeks.’ South Africa’s grant system was suffering staff shortages, technical glitches and notoriously long queues at grant collection points by then already, having ballooned since the ruling African National Congress was increasingly relying on income grants to feed people in its country. In 2019, South African unemployment had approached thirty percent.

‘I tried phoning SASSA but their number doesn't work’.

Getting through to the bureaucracy

Joan Groenewald who lives in Parow with her mother was rejected for the grant because SASSA erroneously listed her as receiving an income. She kept phoning and phoning, however, until she got through. ‘But when you finally reach a person, they say, oh, once it’s been declined, they can't assist, because that needs to be done via email. Then it's like sending emails into this abyss and just never getting a response back’. Still, she kept trying. ‘I then spoke to someone who miraculously said she could do a telephone inquiry. That was about maybe two months ago. When I followed up on that she said it was still pending, it was assigned to someone, there’s no response. I asked if someone could please get back to me with feedback, but that was not possible. You’ll hear from us when you hear from us’.

Shakeera Baker now relies on help from friends in her Western Cape township, Ocean View, with its pink and blood-red buildings etched into the jagged outline of Table Mountain. Ocean View is a direct result of the erstwhile Apartheid Group Areas Act which forcefully removed people of colour from their homes in the 60s, into racially segregated township areas of disadvantage and a lack of access. The past 27 years have seen little improvement. Ocean View’s residents are part of the at least eighteen million people (about a third of the population) who now rely on social grants. There are soup kitchens now in Ocean View, too; an integral lifeline to many people in townships since the pandemic began.

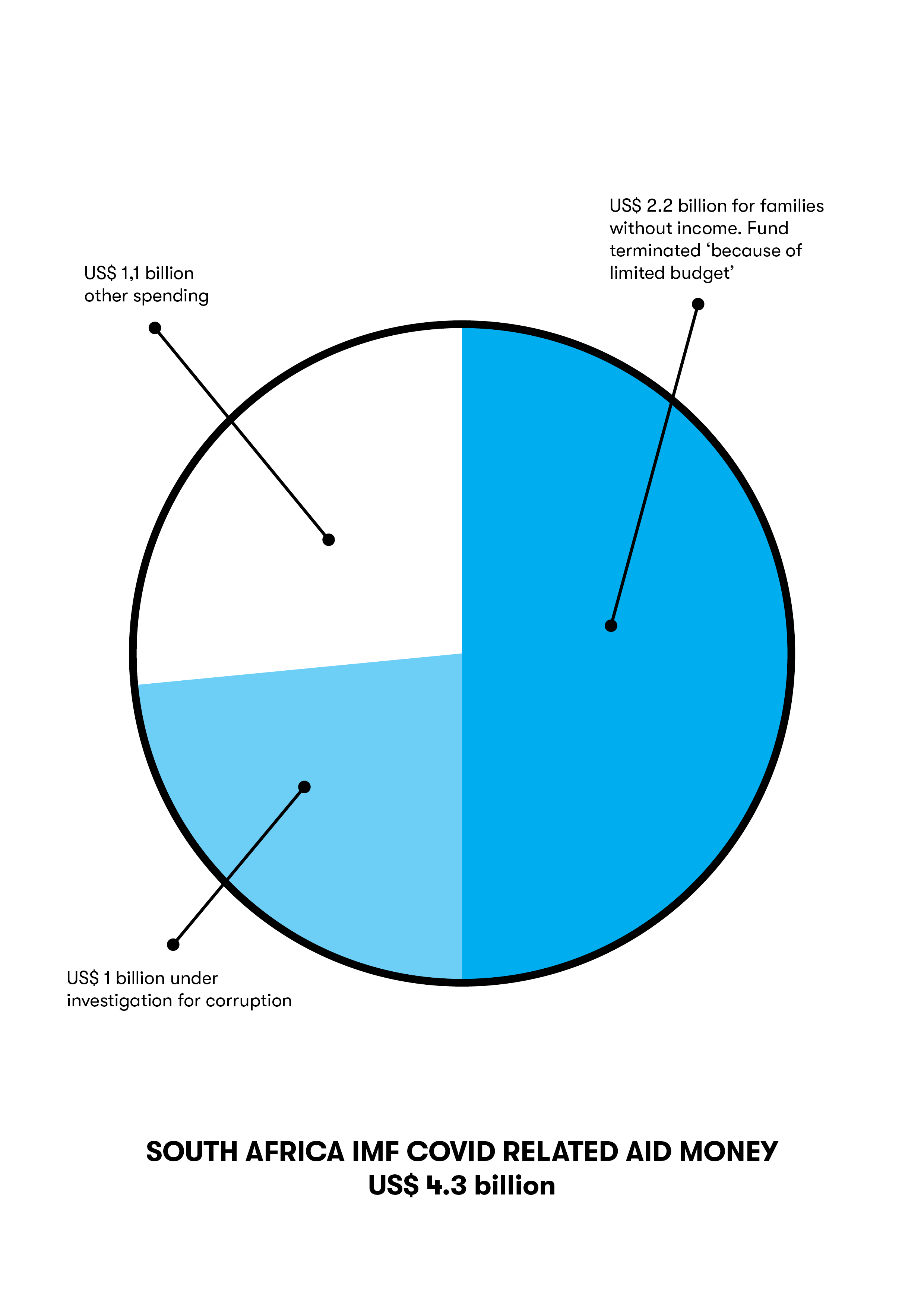

Baker is one of thirty individuals in Western Cape townships whom we asked if they had applied for, and/or received, the much-vaunted COVID social relief grant, for which over US$ 1.5 billion (later augmented to close to US$ 1.8 billion) was made available by the South African government with the help of a total US$ 4.3 billion COVID grant from the IMF to that country. Respondents to our 30-person mini-survey were aged between 19 to 57, with 19 being female, ten male and one declining to say. Almost half of these, thirteen, had applied for the grant but like Shakeera Baker did not receive it, even in cases where approval was noted. A further three respondents though eligible, could not apply due to lost documents. Only three out of thirty respondents had found the application process ‘easy’.

Of the thirteen who did not receive the grant, several were rejected by the system because of wrong information on the side of SASSA, which had them erroneously listed as recipients of other basic grants, unemployment benefits or study loans. The faulty information, based on a set of government databases each of which was also wrong or outdated, proved to be an unsurmountable bureaucratic obstacle in most cases.

Selling vetkoek

Nosipho Duma, now living in Delft township, thirty-five kilometers east of Ocean View, once received financial support for her studies, but has long since dropped out of school to stay home to care for a family member. However, with the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NFSAS) still linked to her name, she was rejected for the COVID grant. She now works part-time making vetkoeks (a traditional fried dough bread), to contribute toward her household of nine, which includes her grandparents, while still trying to appeal SASSA’s decision. ‘I don’t know how to do this. I tried to call NFSAS but I can’t reach them. It takes hours on the phone and I still didn’t get an answer yet’.

Below the food poverty line

According to the statistics bureau Stats SA’s figures from 2019, thirty percent of South Africa’s fifty-eight million population benefited from a grant in that year (translating to over forty-five percent of the country’s seventeen million households receiving one or more grants). Grants were also the second most important source of income (forty-six percent) for households after salaries (sixty-two percent), and they were the main source of income for about one-fifth of households nationwide. Since then, the pandemic has brought another loss of about 1.4 million jobs in 2020 alone, adding another seven million individuals into this picture.

Newly-wedded Natheerah Isaacs, who lives with her husband and child in a backhouse on her parent’s property further to the south in Tafelsig, was denied the COVID grant because the system said she was receiving Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) benefits (UIF is a limited reserve made up of employer and employee payments that provides a small cushion after employment ends, but usually quickly runs out). Isaacs had not received any UIF support in over a year but decided not to fight the decision. ‘I can’t ask every time. I’m gatvol man. If it wasn’t for the soup kitchens and God alone, I don’t know how we would even be standing here. I had to sell my toaster and TV at Cash Crusaders but that’s nothing new, or out of the norm’.

Jane White, also in Tafelsig, was rejected because the system said her and her husband’s two children were receiving child support, which wasn’t true. ‘I had applied for child support in the past three years but it was previously declined because my husband had a salary. Now he lost his job because of the pandemic and we are both not working. So we applied for the COVID grant, only to be denied because they say we are getting social grants for our children’. Rendered homeless, the family has moved in with White’s cousin.

Grants in South Africa

Grants in South Africa vary from five hundred Rand monthly (US$ 36) in child support to close to two thousand Rand (US$ 143) monthly for pensioners. NGOs have calculated that an individual in this country needs at least ZAR 585 (US$ 42) per month to afford enough food to survive. The COVID-19 grant of ZAR 350, US$ 20, is well below the food poverty line.4 The COVID grant payments were stopped, amid protests, at the end of April 2021.

Default decline

Community activist Mary Iadica is one of the few who managed to get her rejection overturned. When she received a notification of decline shortly after her application, she managed to find an email address. She wrote in, demanding an explanation for the decline. It worked. ‘Maybe two days later, when I checked, it said ‘approved’. But how many people are like me, who will write that email and say, explain why I’m declined’?

Iadica, who has been running a non-profit organisation that assists people to set up their own domestic worker businesses, as well as – since the start of the pandemic – a soup kitchen, is savvy. Most people in-line at her kitchen would not be able to do what she did; most don't have enough data to even complete the online grant application, or are not aware that it exists. ‘They are hungry, so the first thing I ask them is, where’s your SASSA? Why didn’t you get your SASSA grant?’

To help them, from the start, Iadica offered to complete applications on their behalf by using her cellphone. Then experiences that, in their cases too, she received rejection after rejection for each person. ‘It ranged from claims that they were receiving UIF benefits to saying that they were registered employees somewhere.’ In reality, none of the applicants she helped were receiving UIF and some had never been formally employed in their lives. ‘Every application is on a default decline. That’s what I think’, she says.

COVID looters

While relief for needy families in South Africa is riddled with delays, mistakes, and fraud, those with direct access to the country’s state coffers have souped up 13,3 billion Rands – close to US$ 1 billion- in shady contracts. This amount is presently under investigation by South Africa’s Special Investigating Unit SIU. Though the investigations may shed some light on the value of these contracts – or the lack thereof — in the future, the money is unlikely to be paid back to the state. The amount, paid out to 1774 ‘service providers’ since the start of the pandemic, is over half of the entire sum allocated by South Africa’s Social Welfare Agency SASSA in relief grants to seven million needy applicants.5

‘We didn’t have money for a respectful funeral arrangement’.

Hermanus-based fellow activist Vanessa Swanepoel says she is aware of ‘thousands of people’ who have been rejected for the grant. ‘The experience is frustrating and confusing. (They reject) people who haven’t worked for years, saying they have income. Then there are a huge number who do not have IDs’.

Two respondents in our survey, who asked to be named only as Asemahle and Sam were unable to apply for the grant because they lost identifying documents6 due to unstable housing situations. Likewise, Maka, a grandmother from Nyanga township in Cape Town cannot apply because she does not have an ID, even though she lost her husband to COVID 19 and now has no income. ‘We didn’t have money for a respectful funeral arrangement’, she says.

The UIF mess-up

On 30 June 2020, the South African government published a media statement admitting to erroneous COVID grant rejections.7 In the statement, SASSA acknowledged that an error in its database had resulted in rejections of almost half of all applications, and that most of these rejections, seventy percent, were due to erroneous listings of applicants as UIF beneficiaries. It also said that a reconsideration process had subsequently revealed that eighty-five percent of people who had been rejected in this way, actually qualified to receive the grant. In the statement, SASSA CEO Busisiwe Memela added that the agency would be working with the Department of Social Development to ‘finalise the modalities of the appeals process for applicants who still feel that their applications were rejected unfairly’. Memela would later claim that ninety percent of qualifying applicants were now receiving the grant, but we were unable to check this.

Government employees

While many face hurdles to receive the monthly COVID grants of US$ 20, some bureaucrats within the system have used their access to pocket the money for themselves. On 2 September 2020, about five months into the start of the COVID grant scheme, Social Development Minister Lindiwe Zulu admitted in parliament that ZAR 1400 million, around US$ 100 million, was paid out to ‘applicants who had other income’, among whom were government employees. Zulu was referring to a report published that same day by auditor-general Kimi Makwetu8, which audited the Covid-19 relief funds. ‘We identified that somewhere around 30 000 beneficiaries require further investigation’, Makwetu said in the report, adding that ‘among these are people working in government’ and that there was a risk of ‘collusion’ between government employees and ‘syndicates’. Makwetu also called the databases that SASSA used ‘outdated’ and acknowledged that these ‘could have led to the rejection of applicants that should have received the grant’.

On 25 March 2021, the Democratic Alliance, the country's main opposition party, demanded that concrete action should be taken by the social development department to recover at least ZAR 85,000 (over US$ 6000) in grants that was fraudulently paid to 241 state employees since May last year.

Most of the fraud was connected to infiltration of the agency by criminals.

Earlier, in October 2020, the general state of the grants payment system was already laid bare when Minister Zulu revealed that SASSA itself was defrauded of over ZAR 50 million (over US$ 3,5 million) in 2019. Reimbursement of the lion’s share of this sum was achieved to the amount of R 45 million (over US$ 3 million), but SASSA still spent almost R19 million (US$ 1,3 million), recouping its losses. Most of the 23,240 cases of fraud reported in that year were connected to infiltration of the agency by criminals who accessed the system and, using genuine grant beneficiaries’ details, re-issued benefit cards for themselves, thereby preventing the genuine beneficiaries from receiving their money. According to SASSA, 19,448 of these cases have been resolved. Over eighty people, including SASSA officials, as well as (former) police officers have been arrested over grant fraud.9

Stolen food

Food parcel delivery programmes were put in place through relevant municipalities, also covering the townships where we conducted our interviews, but out of the thirty people we spoke to, none of them had received any food parcels from government. Most respondents said that they had never heard of food parcel distribution by the government; the soup kitchens and community feeding schemes they accessed were privately run by NGOs. Clips on South Africa’s social media have shown municipal councillors and officials loading food into their own private vehicles. News reports have also said that money for food parcels made available to municipalities has been stolen.10

African governance and politics expert Loren Landau, associate professor at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, says that the corruption problem is a longstanding one. ‘There is little associated with South African service delivery that is not rife with corruption. Whether it is procurement, tendering, or the distribution of resources, this rarely happens in ways envisioned by law. To date, there have been few senior people held responsible for corruption. This only provides fertile ground for additional irregularities’. Landau adds that ‘given the investments of powerful actors in maintaining the status quo, it is unlikely that change will happen without considerable effort from the judiciary, civil society, or opposition parties’.

With regard to civil society, human rights activist Vanessa Swanepoel in Hermanus concurs that NGOs and independent experts could help the state to get its house in order if the state would only allow such cooperation. ‘You can use authenticated NGOs that are actually working in communities, which are not part of the systemic corruption. You can sort out your systems by finding the best systems analysts in the country rather than using the best tender (state contract) to sort out your identification and implementation systems’.

Questions unanswered

At the end of this investigation, answers were sought from SASSA and the Department of Social Development on a number of questions relating to their capacity and their vulnerability to corruption. Several months were spent on this effort. Issues put to both institutions included questions about the completeness of databases, processes, staff capacity, prevention measures to ward off corruption, investigative capacity with regard to fraud risk, and citizen accessibility.

SASSA spokesperson Paseka Letsasi and media correspondent Omphemetse Molopyane were approached several times both by email and phone, but no responses were received. The same was the case with the Western Cape Department of Social Development, which was approached, also by phone and email, through listed spokespersons and officials. Phones just rang and official emails were either not responded to or bounced.

With regard to government employees applying for and benefitting from COVID 19 relief grants, mails to the spokesperson of the Minister of Public Administration, Senzo Mchunu, also bounced. A listed phone number was eventually answered by a call centre operator, who attempted to put us in contact with the minister’s office, but, after ten minutes on hold, the operator came back to respond that the office was unable to take our call. Follow-up efforts made for the next two weeks also remained in vain.

The COVID grant was the ‘hardest South African project’.

During this process, on 18 April 2021, South Africa’s Sunday Times suddenly published an opinion piece by SASSA CEO Busisiwe Memela, in which she admitted that the COVID 19 grant scheme was ‘the hardest South African project she had ever been involved in’.11 As said above, in the article Memela also admitted that the agency had been ill-prepared for a sudden inflow of close to ten million new applicants, saying that changes to the payroll ‘normally take four to six weeks’ ‘and we had only two weeks’. While recognising that the absence of a ‘comprehensive database reflecting the employment status of all citizens in this county’ was a major problem, she seemed surprised at the agency’s ‘discovery’ that many poor South Africans have no access to individual bank accounts or cell phones. The agency’s subsequent change of tack to going through the Post Office ‘exacerbated queues,’ she said. After noting that the agency is ‘still grappling’ with how best to deliver grants to the people, Memela nevertheless concluded that ‘we have learnt much and come out stronger’.

As this report was about to be published, South Africa was shocked by the revelation that Minister of Health Zweli Mkhize himself had allocated ZAR 150 million, close to US$ 11 million, to a ‘communications company’ owned by personal friends of his. The company, Digital Vibes, was paid to ‘facilitate press statements’ by the Minister, an expense deemed unnecessary since each minister has a spokesperson, a communications office and can in addition also use the government’s overall communications service, GCIS. It was later revealed that Mkhize’s family also directly benefitted from the Digital Vibes contracts12. Mkhize has since been placed on special leave by the President.

Notes

- Baker’s husband was the applicant, because as a mother of children who receive child support, Shakeera Baker wasn’t eligible herself. One of the requirements to qualify for the COVID 19 grant was that the applicant was not receiving any other form of state assistance. This requirement has had a deleterious impact on women, since they can barely feed their children with the child support, yet were disqualified from seeking further help. This situation got even worse for women caregivers when the top-ups to the existing child support grants stopped in December 2020, while the women were still not receiving the COVID grants.

- See: Household resource flows and food poverty during South Africa’s lockdown.

- See: Sunday Times, 18-4-2021.

- See: Stats SA—General Household Survey.

- See: Covid looters dodge prosecution & SIU to recoup some of the R13.3bn spent on corrupt PPE contracts.

- Because of the pandemic, services by Home Affairs were limited, thus further making it difficult for people to get temporary ID documents.

- See: SASSA on review of declined Coronavirus COVID-19 grant applications.

- See: Auditor-General South Africa—First special report on the financial management of government's Covid-19 initiatives.

- See: 72 people arrested as Sassa card related fraud soars.

- See: Corruption Watch—Government to tackle food parcel corruption. There were also reports that food parcels were distributed on the basis of allegiance to the governing party. In the past, parties like the ANC have distributed food parcels as part of their election campaigns.

- See footnote 3.

- See: Exposed: Digital Vibes bankrolled maintenance work at Zweli Mkhize property.