He declares that taxpayer’s money should be utilised for the good of the people, but he also passed a pension law that provides him with six cars to be replaced every three years. As Lagos State governor he boosted its internal revenue more than tenfold. He is also the 'Godfather' of Nigeria's new rulers. Bola Tinubu invigorates hopes for change in Nigeria.

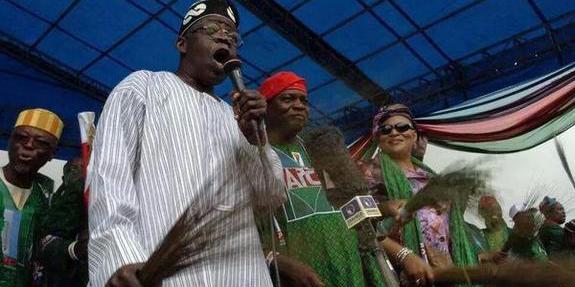

The cheering sets in as soon as the crowd in the gallery spots the small figure in his white kaftan strolling over the tracks of Teslim Balogun Stadium. The voices swell to a roar when the frail man begins to climb the gallery steps. He squeezes a path through the horde of young men wearing hats and t-shirts with the logo of Nigerian opposition party APC; he is applauded, patted on the shoulder, blocked in his way. Once he even has to shove his round spectacles back onto his nose, the glasses having shifted in the commotion, but he remains perfectly calm, like a man accustomed to such attention.

The voices swell to a roar when the frail man begins to climb the gallery steps

It is December 11, 2014. In a few hours’ time, Nigeria’s largest opposition party will announce the winner of its primaries in this stadium in Surulere, a middle-class neighbourhood in the megalopolis of Lagos. Then it will become clear that northener Muhammadu Buhari is going to be the presidential candidate for the All Progressives Congress in the coming elections, to be held on March 28.

Judging from the fanlike behaviour of the crowd, you would say the favourite contestant had just entered the stadium, but nothing could be further from the truth. Bola Ahmed Tinubu does not partake in the primaries. Officially the bespectacled man in the kaftan is nothing more than an ordinary party member, but the crowd knows better than that.

The real boss

Tinubu has passed by already, but Babatunde Ajishe keeps yelling. ‘Tinubu nah real oga,’ he shouts in Nigerian Pidgin English. Tinubu is the real boss. Ajishe is one of the many agbero boys among the supporters. These young men without clear means of income are sometimes used by politicians as a paid crowd and at other times for the dirty work, like intimidating the opposition. They are also an important branch of Lagos’ grassroots, which constitutes Tinubu’s electoral base.

Bola Tinubu (62) was governor of Lagos State from 1999 till 2007. After his two terms, he gave his successor Babatunde Fashola, the current governor, a leg up and thus kept his finger in the pie. APC’s candidate Muhammadu Buhari, now the new president, also comes from Tinubu’s inner circle. Tinubu has proven himself the kingmaker.

The new government of Africa’s largest oil producer will meet a colossal task. The ill-equipped Nigerian army, despite support from Chadian and Cameroonian forces, still has a hard time curbing Boko Haram in the north-east of the country; unemployment is rife and two-thirds of Nigerians live off no more than two dollars a day; the country only produces a fraction of the electricity it needs.

Bola Tinubu’s strategy turned Nigerian politics upside down

The People’s Democratic Party of previous president Goodluck Jonathan had won every national election since the reinstatement of democracy in 1999, but for the first time in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic, it was a tight race. To combat more effectively, the two largest parties in the opposition merged into the APC, uniting constituencies in the north and the southwest of the country: a considerable bloc of the Nigerian electorate. It paid off.

Bola Tinubu was the driving force behind the strategy that turned politics in Africa’s largest economy upside down.

The mother of all

Banners with her portrait hung for weeks on the lamp posts lining the streets of Lagos in 2013. Next to the low resolution picture of the veiled woman were some words that said how dearly this ‘mother of all’ would be missed. The banners flapped in honour of the late Abibatu Mogaji, the woman who adopted Bola Tinubu at a young age; the only mother he has ever known. Till her death on June 15 at the age of ninety-six, Mogaji was President of the Association of Nigerian Market Women and Men. Traditionally in Nigeria, the market is the economic heart of society and a political force to be reckoned with.

As a boy Tinubu often accompanied his mother to meetings. From her he learnt the importance of grassroots politics. The experience also turned him into a street fighter. His mother, would send off her son to hand out political pamphlets. Many a time – and not always successfully – little Bola Tinubu had to scuttle off through the market aisles in order to avoid a beating by supporters of an opposing party.

He encountered his other source of political inspiration in the mid-70s when he moved to Chicago for his studies. There he got fascinated by the Daleys, an Irish-Catholic family at the heart of urban politics: Richard J. Daley was the city’s mayor for twenty-one years until his death in 1976.

He admired the Chicago mayor’s well-crafted system of patronage

Friends from Tinubu’s schooldays remember how he admired old Daley. The mayor’s well-crafted system of patronage combined with clever fiscal politics might not always have been entirely democratic, but it did keep the city out of the red.

The diligent employee

Despite his admiration for the Daleys, it would not be until 1992 that Bola Tinubu became active in politics himself. After rounding up his studies as an accountant he returned to Nigeria in 1983 as a treasurer for Mobil Oil. In those days Ben Akabueze was relationship manager at the Nigerian International Bank. He remembers Tinubu as a diligent employee who drove a hard bargain to get the best results for his firm: “He likes to win for the company, an organisation, or a cause.”

The banker and the accountant became friends. Akabueze would experience Tinubu’s loyalty in friendship when the former’s son got seriously ill and had to be treated in the United Kingdom: the biggest financial contribution for the hospital bill came from Tinubu. “He wasn’t even into politics yet, and he needed nothing from me. It showed his generosity of spirit.”

His accountant friend already held strong opinions and he loved a good debate. Still it surprised the banker when Tinubu announced in 1992 that he would go into politics, this at a time when the umpteenth military regime since Nigerian independence seemed to be opening the door for democracy. Tinubu proved his political savvy by winning the senate seat for Lagos West, the most competitive district of Lagos.

Nigeria was not to enjoy democracy for long, as the military regime annulled the Third Republic’s presidential elections. Not long thereafter General Sani Abacha seized power, and for many Nigerians in politics, journalism and civil society, Nigeria got too hot to stay in. Bola Tinubu went into exile in 1994.

Democratic movement

“This is how we all sat, around a table such as this one,” Professor Ropo Sekoni says in his parlour in the Lagos suburb of Ikeja. He points at the armchairs surrounding the salon table. “But Tinubu never stayed on his seat, he was always moving from one place to another.” The professor describes the first time he met Bola Tinubu, in the mid- 90s, in a living room in Bowie, a city in between Baltimore and Washington D.C. It was a meeting of Nigerian exiles who were fighting for the return of democracy.

“Do you understand how much money we will make under democracy?”

Apart from Tinubu’s restlessness and the fact that he went outside every few minutes for a smoke, the professor remembers his constant emphasis on the term ‘fiscal federalism.’ ‘He thought the federal government should release power to the states.’ In his reasoning he always remained a businessman, remembers Dapo Olorunyomi, veteran news editor and another friend from that period. “Tinubu once asked me: do you understand how much money we all will make under democracy? Tinubu loves money.”

At that point the accountant was already a successful trader in real estate. His financial support to the democratic movement and also to the many Nigerians who sometimes ended up penniless in the US or the UK, generated a lot of loyalty for Tinubu. He could therefore count on broad support when he stood for the office of Lagos State governor at the return of democracy in 1999, elections he would subsequently win.

The politician Tinubu made his biggest enemies in the era that followed, when he shoved aside the Alliance for Democracy, the party on whose platform he had run for governor. Ruffling some feathers, he picked old friends and capable professionals instead of party veterans for his cabinet. The frail man from Lagos was also regularly in disagreement with the burly ex-general in the Nigerian capital Abuja: President Olusegun Obasanjo. With Lagos in the hands of the opposition, the president did everything to restrict funding to that state. Tinubu fought back by dragging the Federal Government to court nineteen times.

Under Tinubu’s administration Lagos started to flourish

Under Tinubu’s administration, Lagos started to flourish. The new governor managed to clean up and revive the tax system. When he took office, the internal state revenue was 600 million naira a month; when he left eight years later it had grown to 7 billion.

Part of this money is being invested in public amenities such as infrastructure. “The city was disorderly before Tinubu. Nobody obeyed traffic rules, people didn’t pay taxes and everyone was building without approval,” says Simon Kolawole, a leading political reporter during Tinubu’s tenure. “Compared to the West it might not seem much, but for Lagosians it was an enormous improvement.”

The most egalitarian Nigerian

Thursday afternoon, a few weeks before the elections: Tinubu’s living room, which feels like a hotel lobby, is filled with expectation. The big man is holding audience, and his house on Bourdillon Road, Ikoyi, one of Lagos’ prime real estate areas, is brimming with people. Visitors tip the guards at the gate to inform them when he is at home. Even outside his mansion the agbero boys are jostling, hoping for their share of Tinubu’s generousity.

Four framed pictures of Bola Tinubu flank the room, one a painted portrait almost reaching the ceiling. Waiting on the Louis XVI furniture are two market women wearing earrings with the APC logo. Also seated are five Lagos State Commissioners; an elderly imam dressed in a gold brocade robe; the son of the Oba (king) of Lagos; the young Nigerian pop singer Dammy Krane and his manager; and a man with his very pregnant wife. When Tinubu enters the room they all jump from their seats. In the presence of Asíwájú, as his followers call him – a word which means ‘leader’ in the Yoruba language – you stand up. It is hard to imagine this is the same man who a friend from his time in exile describes as ‘the most egalitarian Nigerian I know.’

Well-known journalist and presenter Funmi Iyanda is worried about Tinubu’s transformation into Asíwájú: ‘Nigerians have a tendency to celebrate their leaders, even the questionable ones. It is time we realise that leaders are our servants, not the other way around.’ In such an environment even the most democratic of minds will become despotic, she feels. ‘It has changed Tinubu. He has inhabited a more authoritarian role, even though it seems unnatural to him.’

“Nigerians have a tendency to celebrate their leaders, even the questionable ones”

Nevertheless, Tinubu is not one of those typically Nigerian ogas (bosses) who cannot bear criticism, and Iyanda knows this from her own experience. As a young journalist she once compared Tinubu with Steve Urkel, the bespectacled character from the sitcom Family Matters. ‘I fully expected him to hate me after that, but I got a phone call saying that he thought it was funny.’ When he took office as governor, he even asked her to join the transition committee that was to come up with a roadmap for Lagos’ future. ‘I never saw such a collection of bright minds,’ says Iyanda. ‘He is good at identifying talent and using people to achieve what he set out to do.’

Meritocracy

This is likely his most poignant difference with the average Nigerian leader: Tinubu is not afraid to gather competent people around him. ‘A leader is successful when he develops other leaders,’ he states in his office adjacent to the parlour full of waiting people.

A constant refrain in Nigeria is that you don’t achieve something because of what you know but because of who you know. Tinubu however is interested in the capabilities of the people he surrounds himself with. An example of this is his successor to the governor’s seat, the technocrat Fashola. There’s also Tinubu’s old friend, the banker Akabueze. His appointment as Commissioner of Economic Planning & Budget was controversial mainly because he was the first ever commissioner who was not Yoruba, the ethnic group that forms the majority in Lagos. ‘Talent is not exclusive to an ethnic group. I’ve always believed in diversity,’ says Tinubu in a voice with a slight slur, his typical tone.

Tinubu's street popularity is not reflected by the elite, as many intellectuals are much less fond of his leadership. At the bottom of that aversion are the endless rumours about his corruption –interestingly, this ‘man of the people’ has also become very rich. Some even call him ‘Lagos’ biggest thief,’ an aspersion they say is supported by the amount of property he has allegedly acquired. The politician behind his desk shrugs off any accusations. ‘If I respond to all false allegations, I would lose focus. Nothing ever stuck, so why should I bother?’

A mall, an airline and a newspaper

One of Tinubu’s most outspoken critics was Segun Oni. As the PDP’s National Vice Chairman for South-West, he dubbed Tinubu ‘the most corrupt politician in Nigeria.’ The luxury shopping mall in Ikeja, the majestic Oriental Hotel, an airline and a newspaper empire, these were but a pick of the possessions Oni accused Tinubu of having obtained unlawfully.

But Nigeria is a country where politicians change sides as easily as they change kaftans, and last year Oni defected to Tinubu’s APC. Now he praises his fellow party member for his political astuteness and plays down his own accusations as inspired by nothing more than partisan politics. ‘If by now the anti-corruption people have not gone after him, it means Tinubu has a clean bill.’ Tinubu’s ‘clean bill’ could just be an indication of how difficult it is to find documented evidence of corruption in Nigeria.

The outspoken critic now praises his new party member

At best, Bola Tinubu is a paradox. The politician claims to believe that taxpayer’s money should be utilised for the good of the people and has even lobbied – in vain – for a clause in the APC manifesto about welfare for the elderly and widows. But in his final year as governor he also forced through a pension law that, among other things, provides him with a house in Lagos and Abuja, six cars to be replaced every three years and new furniture every two years, as well as a cook, steward, gardener and other household helps, all to be paid for by Lagos State.

‘You can’t take Nigerian politicians too seriously when they take the moral high ground,’ says Folarin Gbadebo-Smith. According to the Chief Executive of the Lagos-based Centre for Public Policy Alternatives, the political system inherited from the British is organised to extract resources and funding from the country in order to enrich its rulers. ‘Once you are at the head of the political food chain, no one expects you to deliver a service to the people.’

Leaders with vision are scarce. That is why he feels it is would be unfair to brand Tinubu only as a power-hungry godfather. “Then you miss the policy of this man. He is much more a political strategist than a dictatorial personality. Lagos is better off under Tinubu. Whether the development would rate high at a global level is a different matter. But he created an environment in which people can thrive economically.” Many Nigerians do see Lagos as the best achieving state, but given the quality of governance in the country, their standards are pretty low.

A solid opposition

Back to Teslim Balogun Stadium in Surulere, where Tinubu’s appearance aroused so much enthusiasm. The votes have been counted, and it is now clear that former military ruler Muhammadu Buhari will run the race for APC against President Jonathan. When you glance around the emptying stadium, you see artificial grass covering the pitch, tracks divided by neatly drawn chalk lines, and walls freshly painted. This stadium is maintained by the Lagos State Government. It is a striking contrast to the National Stadium deteriorating on the other side of the road under the management of the Federal Government.

The condition of the National Stadium is representative of the country’s government. Buhari will inherit a failing state. The fall in oil prices has cut the state’s revenues by a third. The rulers in the capital Abuja have in the past mainly indulged themselves in looting the country’s treasury with impunity, without caring much for the needs of the people. There is no guaranty the graft will lessen under the new rulers. But they -and this is new- will be more likely to be held accountable for their actions, because for the first time there will be a solid political opposition.

And that might be Bola Tinubu’s biggest feat.

Note: This article was first published before the elections, when it was uncertain who would win. It has since been updated to reflect the victory of the APC and Muhammadu Buhari.

Femke van Zeijl is a Dutch journalist and writer based in Lagos, Nigeria. Her third book and first novel ‘Koning van de barraca’s’ (King of the barracas) was recently published in the Netherlands.

Photo credit: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung/Flickr