Nigeria | Some of Ahmad Salkida's childhood friends are now with Boko Haram

When Ahmad Salkida writes of the ‘Tears of Maiduguri’, the stronghold of Boko Haram in Nigeria, he means his own tears. Because Salkida is from Maiduguri. As a Christian kid in de eighties of the last century, he climbed mango trees with his Muslim friends. When they performed their ritual ablutions, he helped them wash. In turn, they patiently waited for him when he was at church on Sundays. Now, some of the boys he used to know are members of Boko Haram. Many others, Muslims and Christians, are dead.

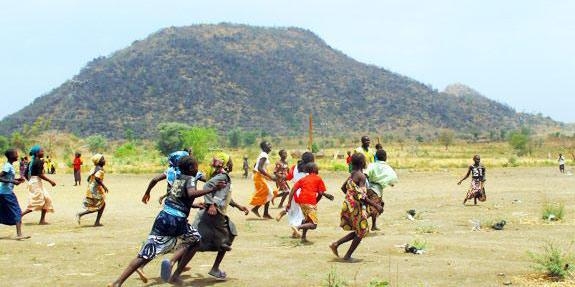

Salkida became a news reporter. In 2006, when the first, still largely peaceful, version of Boko Haram was attracting many among Maiduguri’s unemployed youth, he realised a big story was happening in front of him. Then, Islamic societies, schools and mosques were the only structures that seemed to care for the poor in the north-eastern region of Nigeria, the neglected step-child of the government in the Christian south. In the north-east, seventy-five percent of youth was unemployed; local government endemically corrupt; education, for those who accessed it, delivered only ‘toy diploma’s’; children fought for food scraps with dogs in the street.

A certain Islamic commune seemed an example of a peaceful and just new type of society

Salkida had converted to Islam, seeing the religion as an ethical, socially caring alternative for those who wielded government power. Particularly a certain commune, then still called ‘People of the tradition of the teachings of the prophet and jihad’, seemed an example of a peaceful and just new type of society. The commune’s compound had schools and fruit trees; it offered employment, a home and food for youth who wanted to join.

Scarred by hunger

It was no idyllic ‘kibbutz’ though. Most of the recruits –they counted seven thousand in 2006- were no ‘volunteerist’ students but former street children, scarred by hunger, neglect and abuse and full of anger against the authorities. Salkida, now a beginning journalist for the respected regional newspaper the Daily Trust, was concerned about what he saw as a dangerous mix of radical teachings and resentment. He interviewed the commune’s leader Sheikh Yusuf several times, each time engaging him on his extremist opposition to all that was ‘western’ or ‘Christian’. At some point during their discussions Yusuf offered Salkida the job of editor of the commune’s own newspaper. But when the young journalist asked for editorial freedom to edit out ‘inciting’ speech and for an opinion page with room for frank debate, the job offer was withdrawn.

Yusuf had started expanding the commune, now colloquially known as ‘Boko Haram’, meaning ‘Western education is a sin’, with activists’ brigades, judicial and political structures, and a guard, calling his empire an ‘Islamic state within the state’. Ironically, the nucleus of the new armed core of the movement had been delivered by that very same worldly government. State Governor Ali Sherriff had abandoned a group of armed youth that had helped him win the elections and, furious at this betrayal, the group had joined Boko Haram. In 2007, Ahmad Salkida reported that support for the sect was spreading like wildfire from one part of the northern region to another and that many of the new recruits seemed ready to take up arms.

In 2007, support for the sect was spreading like wildfire

The danger of religious violence in the region was real. A year before, in February 2006, Muslim resentment against their perceived second-class-citizen status had already culminated in rioting, the killing of Christians and the burning of Christian businesses and churches during the worldwide furore about the ‘Mohamed’ cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jylland Posten. After that, apart from occasional skirmishes between police and Boko Haram members, the cauldron kept bubbling slowly. But when, in 2009, twenty members of the sect were shot by a joint military and police team, the movement pledged revenge. Barely a month later, the first armed revolt in Maiduguri broke out.

Banned from Maiduguri

Salkida experienced how it became impossible to live a peaceful life in Maiduguri if you were a young man. “Either you get blown up by the bombs of the insurgents or, when the (army) arrives on the scene, you become an enemy even if you are not one,” he wrote. The government’s forces, now in full terrorist-fighting mode, showed less and less patience with Salkida’s, as they called it, ‘humanising’ portrayals of Boko Haram supporters. In 2009, he was arrested, beaten up, interrogated as to why he had a beard, and threatened with execution. “I urinated in my pants as two police officers were arguing over who would shoot me”, he would write later. After this experience, he decided to start shaving and dressing as a westerner.

Freed after an intervention by a friendly local politician, Salkida was banned from Maiduguri by Governor Ali Sherriff, the same governor whose own militia had joined Boko Haram years earlier. The banning not just inconvenienced his own reporting, but also deprived a range of national media of an important news source on Boko Haram: not daring to send own reporters into the violent region, they had been happy with Salkida’s scoops about the ‘terrorists’. Editorially, however, they followed the government’s line, which was, -simply put-, that radical and violent Muslims were a problem in the north; that local Muslim politicians used the radicals to undermine the government in the south; but that the government was well in control of the situation. With Salkida’s local reporting out of the way, editorial opinionating was all that left and the Nigerian public’s access to news about the insurgency in the north was diminished.

The official line was that there were violent Muslims but that the government was in control

Nevertheless, Salkida’s expertise had increasingly become seen as credible by more progressive media such as the Premium Times, and by Nigerian news websites run by expats in the west like Sahara Reporters in the US and Nigerian Watch in the UK. In 2012, the French agency AFP asked him to assist their reporting on Boko Haram; the BBC followed in 2013.

Failed peace talks

Earlier, in 2011, he had already been approached by diplomats and security operatives who, in contrast to the official government line, did not seem at all convinced that the situation was ‘under control’. Could Salkida help set up peace talks with Boko Haram, they asked. He had readily agreed, but the attempts were unsuccessful. “Political corruption stood in the way’, he would explain later, at a regional journalism conference. “One government representative would agree to certain steps of goodwill, but then another person in government would withdraw that. There were also people who parachuted themselves in, saying they had been mandated by Boko Haram to negotiate. They pocketed government allowances, before being found out as frauds.”

The peace talks failure resulted in a victory for the ‘hawks’ on both sides. Some in government labelled Salkida a ‘terrorist’ again, whilst some of the new leaders in Boko Haram didn’t trust him anymore. As a result, he and his family now received threats from both sides. In 2013, they fled to Dubai, from where he has tweeted since then.

Salkida and his family now received threats from both sides

The movements’ increasingly bloody record in the last few years, -ranging from mass kidnappings of school children to suicide bombings and the massacre of entire villages-, has long since stopped Salkida from even attempting to ‘understand’ the perpetrators. He does continue, however, to call for a more effective government policy to deal with the violence.

Tweeting truth to power

And he is no longer alone. Ever more mainstream media, nowadays, vehemently criticise the lack of government attention to the mayhem and misery in the north. Insufficient supply to military forces in the region (soldiers go without weapons, vehicles, uniforms or even food), resulting in plunder, harassment of villagers, desertion towards Boko Haram itself, are increasingly reported on. When president Goodluck Jonathan condemned the attacks on Charlie Hebdo in Paris, whilst keeping mum on the massacre in Baga two days later, the outrage reverberated through both north and south.

Salkida’s twitter account counts more than twelve thousand by now. More and more diplomats, correspondents, politicians and activist follow it because somehow, even from Dubai, his information seems spot on. His tweet in August 2013, calling the government’s announcement that there was to be a truce with Boko Haram ‘bogus’, was proved right when the movement attacked again in October that year.

Shekau was well and alive

His information was proven right once again when –after the government in September 2014 stated that it had killed Boko Harams leader Abubakar Shekau and published a picture of the dead body-, Salkida tweeted “Mark my words: I have it on authority that Shekau is well & alive, the picture going round is NOT the person who torments us with his group”. The tweet was retweeted 239 times, quoted by established media both in and outside Nigeria, and proved correct beyond a doubt when Shekau posted a video, announcing still more ‘holy war’, on You Tube.

And in November, his tweet about negotiations on the possible release of the two hundred abducted girls from Chibok showed that the government was –once again- being fooled by an impostor. Boko Haram ‘negotiator’ Danladi Ahmadu had “nothing to do with BH as a group or its leaders”, he tweeted, following up with a range of tweets about Boko Haram’s ideology and methods. They would have nothing to do, he said, with a man whose name was ‘Danladi’, which means ‘Sunday’, since the group’s rigid ideology would not allow even for talking with a man with such an ‘apostate’ name. The man indeed proved an impostor, the talks were broken off and the girls, Abubakar Shekau stated triumphantly, were ‘married off’.

Increased pressure

Though peace so far is not in sight, the Nigerian government is now increasingly under pressure to stop pretending that it is in control. It must, the chorus of critics says, engage with the north, equip its soldiers, fight corruption, and address social misery: all things Salkida has been saying for years.

Meanwhile in Maiduguri, he notes, many Christians now bury their dead like the Muslims, immediately into the ground; “because there is hardly any space in the mortuaries anymore”.