After the War on Terror against the fundamentalist Al-Shabab, a new war is being waged in Somalia.

This time, it’s a war for the fertile lands on the side of the beautiful Shabelle river, which feed cattle and grow mangos, bananas and papayas. A disadvantaged community of families, called the Habargidir, has invaded these lands and challenged the traditional reign of the richer Biyamal landowners here. During November 2013, four bloody clashes left hundreds dead, thousands displaced, a settlement burned, farms taken. The poor clan has won, for now. But the Biyamal are fighting back.

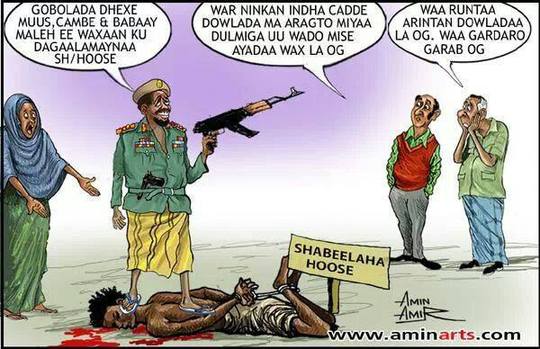

People have been shot here for not understanding the rules of the bribery game

It is early in the morning on Saturday, February 22, when I take a taxi from Mogadishu to Wanlaweyn in Middle Shabelle. The road is ravaged by our recent wars and car trouble because of the large potholes and obstacles are a real danger. If this is not enough to make the traveler nervous, there are also the many informal ‘checkpoints’ where men in army uniform demand bribes. People have been shot here for not understanding the rules of the bribery game and not paying fast enough. Luckily, our driver knows what he needs to do.

It is in Wanlaweyn, in the interior, where most of the now-displaced Biyamal elders reside. The members of this clan –a clan is like a tribe, but usually smaller and more localised-, came here from KM 50, the area fifty kilometers south of Mogadishu, where they used to live, after it was invaded by the Habargidir. Ever since then, there has been fighting, and much destruction, in that place.

The terrorists did not disturb

Biyamal clan elder Aweys Abdullh Omar (40), traditionally dressed in long robes, is sitting at a restaurant drinking tea. He is sad, he says. “After many years of peaceful coexistence with the Habargidir, the invasion came suddenly. It happened almost immediately after Al Shabaab –which had controlled the region firmly up to 2012, MG- , was defeated.” At the height of the armed Islamic insurgency, even Al-Shabab had not dared disturb the Byamal’s ancient way of life. The terrorists had roamed the area and waged war on Marko, the nearby regional administrative capital. Middle class people and intellectuals, -those who had funds to travel-, all left for Mogadishu. They had left the poor of Marko to eke out a living like they had always done, providing services to the Al-Shabab troops and the ruling Biyamal alike.

Omar cannot understand why the Habargidir suddenly felt a right to the land

Omar says he cannot understand why the Habargidir ‘suddenly’ felt they had a right to the Biyamal area. “This is the richest region in Somalia. The most important river runs here. We allow other clans to live in the region, but we have to have our own administration.” In fact, after 2012, a governor from the Biyamal clan had resumed duties in Marko town, but his office was also invaded and taken over by the Habargidir militia. Omar: “We are the designated clan to administer our region. We will respect others as long as we are also respected.” His fellow elder, Ali Yusuf Borri (50), is the chairman of the now ousted Unity Council of Middle Shabelle. He says he is traumatised. “I have become thin now that the region is ruled by invaders,” he says.

The argument made by both is that Somalia is a federation. “Federalism allows every region to be ruled by its population”, says Omar. And Borri: “We have a constitutional right as a community to govern ourselves. If all Somalis abided by the provisional constitution and the provision for rights for every family, clan and person, there would be no fighting.”

Both feel that the Biyamal have been abandoned by the Somali government –worse, that the government is helping the Habargidir. Borri: “The men who invaded KM 50 were dressed in Somali military uniform and armed with the most modern weapons bought by the government.” Many observers concur: the invaders did seem to have the support of at least the Third Brigade of the Somali army, most of whom are ethnic Habargidir. The commander of the Third Brigade, general Roble Jimale, is said to be a good friend of Habargidir warlord Yusuf Siyaad Indha’ade, who is in turn a good friend of Security Minister Abdikarim Guled. It is almost as if, after decades of efforts to establish central state rule, old fault lines in Somalia are shining through the cracks again.

Because the Habargidir have their own story to tell.

Shoe shining and knife making

I put to the elders what members of the Habargidir clan, among whom former MP Ugas Mohamed Bashir, have told me. That they have always been outcasts, discriminated and victimised, ever since they, in the 17th century, rebelled against the powerful Ethiopian empire but lost, and were enslaved. That they had been forced to live in refugee camps next to the Ethiopian border for decades during the times of colonisation. That the Ethiopians felt –with agreement from the colonial powers at the time, some say- that these ‘insurgents’ should be taught to be servants, horse riders, blacksmiths, shoe makers and tailors, and that they should not ever have political power again. Other communities in Somalia were made to look down on them and only use them as servants. Even nowadays many people would not allow their daughters to marry any Habargidir. Can the Biyamal understand that in modern Somalia, Habargidir have pinned their hopes on the new government to help them have rights, too?

In modern Somalia, Habargidir have pinned their hopes on the new government to help them have rights, too

It is true, the two Biyamal elders admit, that the Habargidir have always been the poorer and more exploited. But Omar doesn’t feel that that is enough reason for the Biyamal to give up what they have. “We struggled for our rich region, we built it. Why are their regions poor? Why can they not build their own regions?” Omar and Borri know, of course, that the Habargidir have lived in this Shabelle region since the mid-seventies of the last century, when the clan had to flee the drought-ravaged areas in Central Somalia where they had settled. Former ruler Siyad Barre had evacuated drought victims with helicopters to resettle once again, in Middle Shabelle. “This is where the problem started,” says Borri. “Siad Barre took farms from us to help them. But really these are not their farms. They have been harassing us about our property ever since Siad Barre was ousted.”

“They have many weapons and just want to get rich from selling our vegetables”

Omar says that he has tried to reason with the Habargidir. “We have said to them, ‘Live with us peacefully or otherwise leave from here.’ But they said no. They have many weapons and they just want to get rich from selling the vegetables from our region.” In the meantime, passers-by, all Biyamal, have joined the conversation. Local Mohamed Nor Jinow fully agrees: “I, my father and grandfather were born in Middle Shabelle and we are fed up with these families who hail from the central Somali regions. Now they are killing us with these modern weapons from the Somali army.”

Fighting until the last girl

Omar threatens further bloodshed if there is no ‘redress of the Biyamal’s rights’. “I was born here. We will fight for our rights until there is justice again and we are in charge of our own region.” And, using a traditional phrase which means that all the men and even the women will wage war: “We will fight the invaders until the last girl from our clan is left alive. We will even set the seas on fire to chase the invaders from our land”. Borri agrees: “They are now forcing us to fight back. We cannot have our autonomy destroyed.”

"It is impossible to solve regional bloodshed in two days’ time.”

How about peace talks, as proposed by the federal Somali government? The Biyamal elders clearly don’t see this as a viable option. “They haven’t embarked on a negotiation process so far”, says Omar. “They like to do ‘reconciliation conferences’, sometimes with the partnership of international agencies. Then it will be two days of talking. It is impossible to solve regional bloodshed in two days’ time”.

A central issue to the Biyamal cattle herders’ objection to the Habargadir claiming ‘rights’ in Shabelle is that the Habargadir are vegetable farmers. To farm vegetables, they need land and that, the Biyaamal fear, will impact on the grazing space for their cattle and also lead to deforestation. Upon leaving Wanlaweyn, on the edge of the town, I meet pastoralist Mudey Nurow Abdi (39), who confirms that he and his fellow herders are ‘fed up’ with the new farmers from Habargidir. “They dig up our grass land. And they chase us away from it.”

Waiting for the rightful owners

In the administrative regional town Marko, ousted local governor Mohamed Abdi Keerow is waiting for reinstatement by the federal government. Or his Biyamal clan reconquering their lands. Or both. Though he has had to vacate his office, he still lives in his local governors’ residence, with a bodyguard, and a pistol that remains close to his hand even during our interview. “I am planning to take my administration back”, he says. “They killed many innocent women and children in KM 50. I can’t allow that.” He sees the Habargadir as ordinary land thieves. “During their invasion, they took farming land. This was the reason why they invaded my office: because they feared I would return the land to the rightful owners. They wanted to kill me, but I managed to escape.”

The governor is planning to take his administration back

The district of Afgoye is closer to the capital, Mogadishu and a safe distance away from the KM 50 settlement, where fighting still rages. It is only here that I can safely talk to members of the Habargidir community. Elder Mohidin Jama’ Salad (67) elder of the Habargidir clan, denies that his people ever harassed the people in the region. “We were excluded from administration of the region by the Biyamal. We never had rights. But we own land, and animals. We have been living here for a long time. Why do our (Biyamal) brothers refuse our right?” Fellow Habargidir youngster Guled Farax Kheyre (20), standing in front of Marwaz secondary school and dressed in secondary school uniform, calculator in his hand, says he was born in the region and still studies here. “My father and my grandfather have farms here. Why can’t we be elected to be governor? The federal system doesn’t forbid that. It is our Biyamal brothers who are denying us justice.”

Al-Shabab attacks at night are usual

In the night there is gunfire: Al-Shabab militants have attacked the police station. I ask the people in the hotel what happened. “Al-Shabab attacks at night are usual”, is the answer. Is it Al-Shabab or the Biyamal counter attacking? The Biyamal elders have denied statements by Somali deputy defense minister Hussein Ali that ‘Al-Shabab militants are arming them’ and that ‘the terrorists are wearing Biyamal clan shirts’. But it is also a known Al-Shabab tactic to profit from other tensions in the country, fanning flames where they can. And Al-Shabab still also attacks randomly.

Still, the accusations of the deputy defense minister have done little to inspire trust in the Biyamal leadership, and the wisdom of including Hussein Ali in a government committee that must now establish ‘reliable administration’ and stop ‘land- based fighting’ in the region can therefore be questioned.

Muno Mohamed Gedi (19) is a free-lance journalist in Mogadishu, Somalia.