The sonic migration moves of Mo Laudi

Between the African continent and Europe stretches more than distance—there’s a charged field of echoes, migrations, and imagination. Globalisto: A Philosophy in Flux – Acts of an Imbizo was a landmark exhibition curated by Mo Laudi (Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape), held from 25 June to 16 October 2022 at the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole (MAMC+), France. It convened 17 artists from Africa and its diaspora, alongside researchers and thinkers, to propose a vision of Black aesthetics beyond borders.

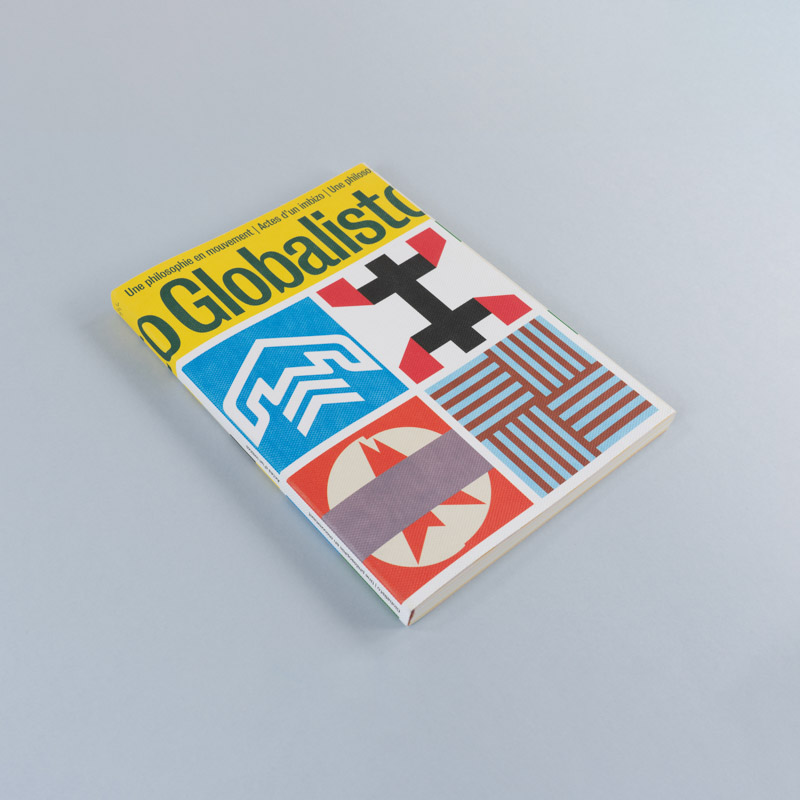

A two-day symposium on "Art and (De)colonisation" accompanied the show, generating a hybrid publication—part catalogue, part philosophical archive—co-edited by Mo Laudi and Alexandre Quoi. Published in April 2024 by MAMC+ and distributed by Les Presses du Réel, the 180-page bilingual volume features contributions by Achille Mbembe, Christine Eyene, Norman Ajari, Elsa M’Bala and others, with interviews, visual essays, and a companion playlist. Globalisto is not just an exhibition or a book, but an invocation—of ancestral frequencies, Pan-African futures, and decolonial imagination. In this exclusive interview for ZAM, Mo Laudi reflects on dismantling borders—not only between nations, but within consciousness itself.

Layered experiences

Heidi Sincuba: What early influences shaped your creative practice?

Mo Laudi: I’m originally from Limpopo, from a deeply intellectual and political family. My father was involved with the ANC at some point, and he was also a university lecturer who later became a doctor and then the president of the African Mathematics Union. My mother was a university director. So our home was filled with books—Ngūgī wa Thiong’o and many others. Yet at the same time, I was playing barefoot in the townships, moulding clay in my grandmother’s village, and absorbing all these layered experiences.

I went to Model-C schools [formerly whites-only public schools in South Africa that, after apartheid, were semi-privatised and allowed limited admission of Black learners—often maintaining racial and class hierarchies] post-1994, and my parents encouraged me to take private art and music lessons. I was also doing graffiti, which my parents recognised as something more than vandalism. They encouraged me to channel it. Learning about Gerard Sekoto [one of South Africa’s most celebrated modernist painters, known for his vivid depictions of Black urban life during apartheid] — realising he was from the same neighbourhood — made me feel like it was possible to follow that path. Sekoto was an artist living in Paris, creating a life that I could imagine for myself as a child. That was a dream. But that dream got buried, partly because of fear of the ‘starving artist’ life. So, to play it safe, I chose to study advertising instead.

HS: At what point did Globalisto start to take shape?

ML: After studying, moving to London, and joining various music groups, my focus shifted. I tried to find work in advertising, but jobs were scarce. I also attempted to exhibit some paintings, but that didn’t take off. So art stayed in the background while music flourished. At one point, I toured 50 countries as a DJ and MC. Crossing borders in Europe and the United States brought a consistent feeling of being “othered.” I noticed how fellow white musicians moved through borders seamlessly, while I was often delayed for hours. Visa applications could take weeks. I saw the way that human beings were limited in terms of movement, but yet raw materials from Africa were easily extracted. Music, however, travels freely. Yet many African artists resisted being referred to as “African artists.” Even the idea of the "Global South" can be problematic—why is Europe always the North? Why define Africa through colonial languages: Francophone, Lusophone? It’s still linguistic occupation. These contradictions sparked questions that shaped the philosophy of Globalisto — how can we change the world from a Pan-African perspective, control our narrative, and move freely as the philosopher Achille Mbembe envisions in a borderless world?

I started creating events and exhibitions under Globalisto, bringing together artists from Africa and beyond to explore these questions: What does Afrofuturism mean? Who can claim it? How do we move beyond colonization without constantly framing everything through a colonial lens?

The concept of Imbizo, from the Zulu tradition of village leaders gathering to resolve disputes, became a metaphor for confronting oppressive systems and alien narratives. This idea gave birth to the book.

Remixing

“Flux is roots communicating, feeding each other”

HS: You bring up this idea of flux—of movement, multiplicity. What does it mean for Globalisto to be in flux?

ML: Flux means not being fixed, not being flattened by labels. It’s like the mycelium network under the earth—roots communicating, feeding each other. That’s how I see Globalisto: as a living network. We don’t need external validation. We can create our own platforms, our own rhythms. Art is the space for that. Sonic, visual, philosophical—they all converge. I want to collaborate with artists who think about sovereignty, who remix what the future could be.

HS: There are so many forces at play. But what about the material ones? Publishing in English, through a European press—how do you grapple with those tensions?

ML: It's real. The book was produced in France, because that's where I found the resources. There’s also a French edition. But ideally, I want to see it published in South Africa, in local languages too. Zulu, Sotho, Tsonga. That requires funding and translators. But it’s possible.

The sound and the sangoma

HS: Sound plays a big role in the book, and in your practice more generally. How do you think this book will shift our understanding of Black sonic traditions?

ML: Sound is infinite. You mentioned one time when we had lunch in Joburg that your own research explored the connection between sound and the sangoma—the sangoma as the person of sound. In Abrahamic religions, there’s the idea that the world began with the word, the sound, and that sound’s vibration brings light. Sound plays an infinite role in society.

Growing up, my parents were in choirs singing songs from Mozambique, Algeria, Tanzania, and the training camps. As a child, I absorbed this sense of borderlessness and resistance. Then there was hip hop, jazz, and pop on the radio — a Black Atlantic fusion that connected me to a wider world I didn’t fully understand but deeply felt. I dreamed of streets in New York or LA, with baggy pants, beats, and stories.

In the streets, people sang and danced — the pantsulas, the spiritual layers in church — all this sound and movement created a way of being. Somehow, I was a young antenna receiving these signals, inspired to transform them into my own beats. Sound held meaning and became a force within me, reminding me of home.

You witness the unity of “one nation under a groove”

Arriving in London, sound was a badge of honour, a home away from home, bringing people together. When you play sounds and people move in harmony, dance, laugh, and fall in love, you witness the power and unity George Clinton called “one nation under a groove.” It was a continuation of seeking a space to call home.

I created parties carrying the legacy of musicians in exile, who suffered loneliness without community. Over time, that community grew, and within the music, you feel the life force of resistance and healing. South African and African sounds carry tension and aggression but also healing beneath — a layered composition that I hear in Afro House and Amapiano.

Starting out in London was hard — no home, no space — but eventually, I created a weekly residency that became the first South African music night in the city. It grew rapidly.

I remember DJing at Africa Day in Trafalgar Square, when someone asked for “real African music” while I was playing South African house. The ignorance was striking — they couldn’t hear the realness in Afrobeat and house, but that moment only made the music speak louder.

Framing

HS: That framing—that pressure to simplify—is always there. What were some of the more difficult or unexpected tensions that emerged during the book’s making?

ML: There was a lot. European framing is persistent. Even the funding system—people asking, “Shouldn’t the title say Africa? Africa-something?” Globalisto? Nobody knows what that is. It scared them.

But that’s the point. Why must everything be familiar? I created the term, the concept, the thought. And ideas take time. I’m not interested in something that trends and disappears. I’m thinking long-term—something that grows roots. That shapes the next generation.

That tension is always there. But sound gave me a path. From clubs to museums. From nightlife to Pompidou. I carved out my own lane.

HS: You worked with contributors like Achille Mbembe, Norman Ajari—thinkers we know well. What new perspectives emerge from this book?

ML: (Laughs) You’ll have to read it. I can’t give away everything!

HS: Okay, okay. But there’s definitely a gesture toward the future. What future do you see for Globalisto?

ML: I was recently at Art Basel for a talk with Ibrahim Mahama, Helen Nzete and many others. We called the platform Globalisto: Unifying the Seen and Unseen. It was a meaningful dialogue about the challenges we face, our hopes, and our visions. My aim is to keep building and collaborating — to create new platforms across different spaces.

I'm drawn to this idea of space — spaces where artists and communities can gather, grow, and build foundations. My hope is to create such a space — where Globalisto becomes not just a philosophy, but part of school syllabi, maybe even introduced at primary level or in universities.

These spaces can help us imagine futures, challenge the present and past, and critically reflect on how we are shaped — especially within the technological landscape. Even in AI, you see traces of racism encoded into the system. After all, technology is made by people, and it carries the biases of those who built it — the brains of the past.

Globalisto is still growing. Still becoming. That’s the beauty of flux.

Globalisto: A Philosophy in Flux – Acts of an Imbizo is published by Les Presses du Réel, available in English and French.

Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape (Mo Laudi) is a research fellow at Stellenbosch University. His work spans sound, installation, philosophy and social transformation. He lives between Paris and Johannesburg.