No one goes to Paradise to return from it.

There is a pivotal moment in the great Mandé epic Sundiata, when Sundiata Keita, alias The Lion King, is forced to leave, to migrate. At this point, he is a young man, full of unbridled ambitions and possibilities. For the first time in his life, despite his obvious limp and speech difficulties, despite all the obstacles stacked against him, he is fully aware of his own powers.

This event takes place sometime in the 13th century and the world as we know it is about to change for good. But first Sundiata, the catalyst of that change, has to flee, for the circumstances in which he finds himself in have become unattainable. There is an attempt on his life, not in the least from his own father, the King Nare Maghan. Moreover, the place he calls his home, a tiny, inconspicuous kingdom called Mali, is being threatened by the ruler of the neighboring kingdom, the powerful Somangourou known as a sorcerer.

There is no way out for Sundiata but to flee.

Migration will offer him the possibility to become what he was meant to be, the ruler whom the oracle and soothsayers had predicted he would be.

This is the essence of migration. It offers the migrant the possibility to rise fully up to his potentials. Migration opens doors and makes of man a better version of himself. The world is what it is today largely because of migration.

But migration has its dark sides. Migration can disappoint. The utopia, to which the immigrant is drawn, can turn out to be a nightmare, a prison where his dreams are squashed, where his very existence can become endangered and where it might end.

These struggles are some of the themes which the three films I want to discuss explore at great length: La Noir de by Ousmane Sembene (1966), Touki-Bouki by Djibril Diop Mambéty (1973) and Atlantique by Mati Diop (2019).

The three filmmakers, once migrants themselves, must have witnessed these two aspects of migration, the good and the bad. As a result, in their films, they showcase the possibilities of migration but also the challenges and the questions it posed. They reveal how the paradise promised can sometimes become hell.

It is a well-known phenomenon: Every day, myriads of people from every nook and cranny of earth move from one place to another. Some are called expat, to avoid the negative connotation associated with the word migrant. But even the migrant who has no diploma or certificate is in essence an expatriate. That is the case with many domestic workers, most often young women, from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and even Europe. Life evolves around such a ‘maid’. She goes on and on tirelessly, day in and day out. Sometimes, it is as if she’s a robot, a machine without emotion. She never complains but labor in utter silence. She lives in a shadow, always in the background, with no time on hand for fun. Her world is a world of shadows. She is visible and invisible at the same time. But within her thrives dreams and longings. She carries a whole world within her, and that world constantly calls on her, makes demands of her, often outrageous demands that are impossible to meet.

Caught within the world of shadows and the world within her, the world of home and the migrant world, she feels lost and in a limbo.

This is the image that the father of the African cinema, Sembene Ousmane, attempts to show us with his first feature film and the classic, La Noir de (1966). The film is a rare pearl of cinematography. The heroine, Diouana, is a great beauty: her steps are majestic, her skin as beautiful and black as ebony. Djelis or praise-singers of yore would have song her names through the ages. But Diouana, a domestic worker in the service of a wealthy French couple, is a prisoner of the nightmare that migration has become. In silence, her rage is only visible in slight gestures, we see her slowly unraveling. For what was once considered a paradise, life in France, has turned out to be a nightmare. Migration, the ultimate solution for many, is not the case for Diouana. But she is unable to escape Paradise, for no one goes to paradise to return from it. This is the dilemma of migrants. If the land of destination turns out not to be what was expected, a return home is not always the solution. Such a decision requires courage, resourcefulness and the same ingenuity that was needed to migrate. For the migrant does not fit in that home he had left. Sometimes to escape this fate, this sense of non-belonging, the migrant is left with no other choice but to further sink into despair, which is what happens to Diouana.

There is a scene in which she receives a letter from her parents in Senegal. It a poignant scene that illustrates the dilemmas migrants often face. Her boss offers to read the letter for her. From the film it is not clear whether Diouana is illiterate. But we hear her in a voice over speaking fluent French, which suggest that there is power at play here. The power of the boss to lord it over his worker, the power of the destination country over the migrant, and how that power is sometimes abused. The letter is full of complaints by the parents about Diouana. There is also plea to send them money. We, the viewers, know that Diouana’s salary is kept by her boss, who refuses to pay her, which is the fate of many domestic workers in the world. The letter is littered with requests and reproaches. Home and the longing for home hover like a sharp dagger over Diouana’s life. This is the moment that sets off Diouana’s unraveling. Or can it be read as the beginning of resistance? We see Diouana transform from a young woman always impeccably dressed in western clothes into one wearing African clothes. She even changes her hairstyle into a style worn in Senegal. Diouana goes even further. She demands that the mask hanging on the wall of the house of her boss be returned to her. ‘It is mine, she says,’ with a hard tone. It is as if for the first time Diouanan is demanding the return of her individuality, her essence as an African in a world in which she had been caste afloat.

But even this desperate act seems too late for Diouana, for the world in which she has found herself has become a place where she is unable to attain redemption. So Diouana commits the biggest act of resistance. In one final act, she decides to be true to herself by ceasing to be a migrant.

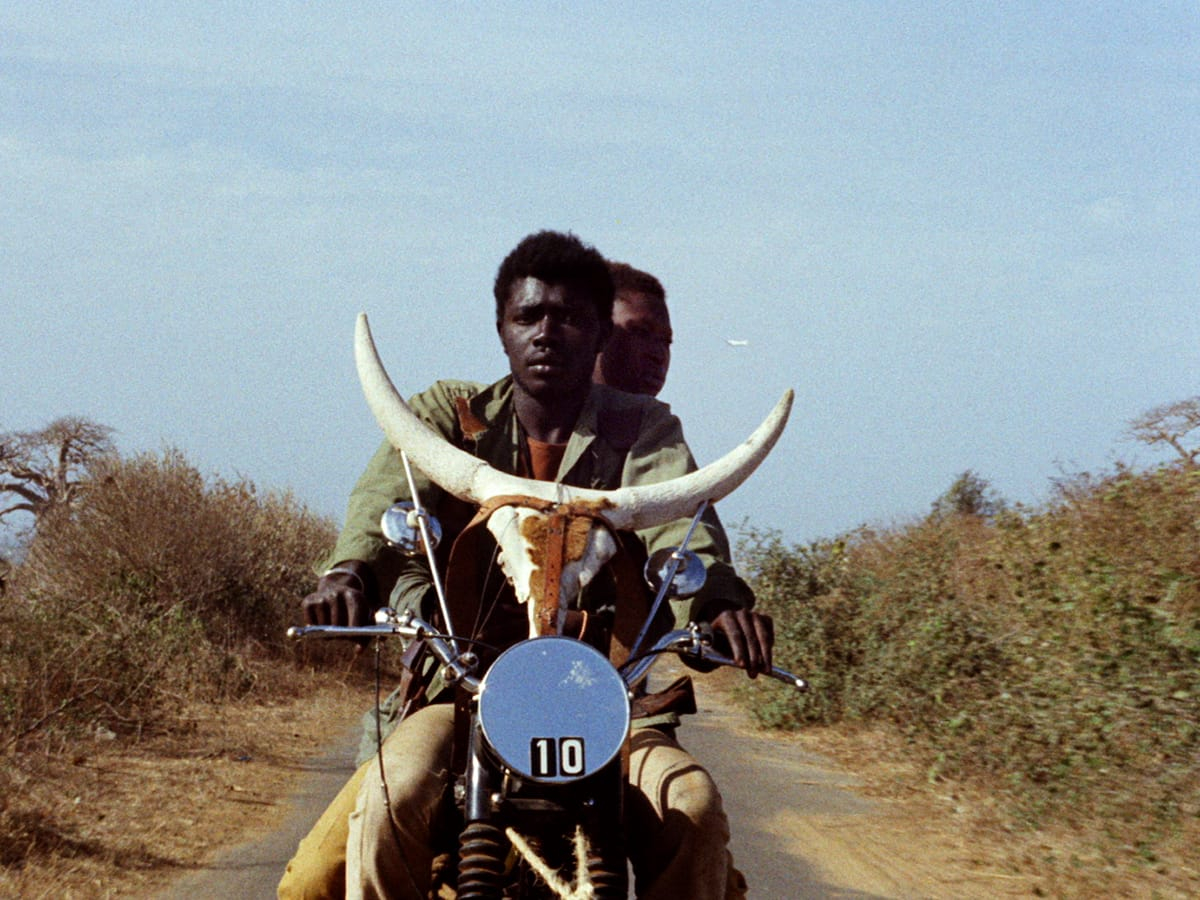

Another aspect of migration, life at home, is explored in a film rife with symbols, Touki-Bouki by Djibril Diop Mambéty(1973). Two young people, Mory and Anta, while roaming their time away riding through the streets of Dakar on a motorbike straddled with bullhorns. The film is an allegory to unbridled longing but also hopeless imprisonment. The bull is doomed to be sacrificed, despite its resistance and hunger for freedom. The bull cannot escape its simple fate as food for people. The two youngsters attempt to escape their fate by dreaming of migrating to Paris, a city whose praises are sang by Josephine Baker in a sultry, beckoning voice. To achieve their goal, Mory and Anta commit robbery, but even with this desperate act, they are unable to escape their fate. On arrival at the harbor to board the ship bound for Paris, the same ship which Diouana boarded, Mory hesitates. He turns around and rushes back to the city in search of his motorbike with the bullhorns. The bull decides to embrace its fate.

But what if the journey undertaken fails? What if the migrant does not arrive at his destination? This is the theme that is tackled with great subtlety and power by Mambéty’s niece, Mati Diop, in the 2019 movie Atlantique. Mati Diop chooses to focus on the effect of failed attempts to migrate on those left at home. She succeeds by making the spirits of the dead at sea return to those who were left behind and in doing so make them see what the migrants saw at the sea, what they experienced. What Mati Diop showcases is the greatest form of empathy, which makes this film, in my opinion, the best of the three reviewed.

But Mati had great teachers to learn from and to lean on, teachers in the persons of the father of the African cinema Sembene Ousmane and her uncle Diop Mambéty who died so young.

These films pay homage to migration in all its facets. They show us the beauty of the human being but also the terrible costs of migration.

They are a gift from these three great masters.

Watch Sundiata here.

Watch Le Noire de here.

Watch Touki-Bouki here.

Watch the trailer for Atlantique here.