The djelis took cultures and traditions across the African continent and even the world. They even resonate in the works of rappers and spoken word artists.

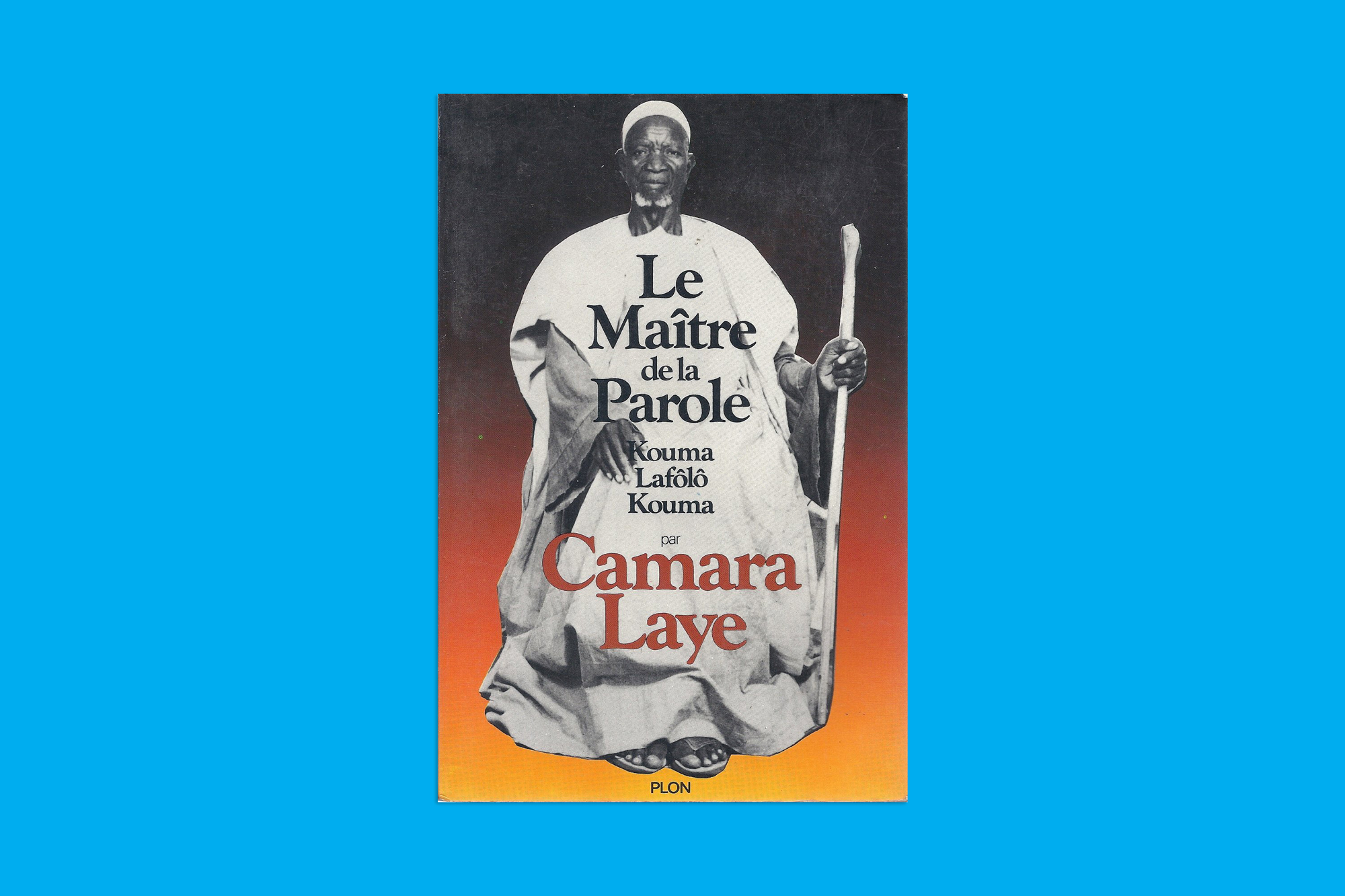

In his seminal work, The Guardian of the Word, Guinean novelist Camara Laye explored the work of Djeli’s in several countries in West Africa. Laye focused on his own people, the Mandé, who are spread across Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Senegal, Gambia, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Mali. In fact, many of the people of Sierra Leone, Gambia, Guinea, Mali, and almost the entire population of Liberia belong to the Mandé speaking language group. This language has its origins in Mali, and it is divided in the Mandé fu and the Mandé tan group of languages, meaning that number ten ends with fu in one group and tan in another.

Camara Laye was a great writer. His first novel, The African Child or The Black Child, was compulsory literature in many schools in Africa, including my birthplace Liberia. He became world famous with his novel, The Radiance of the King, an allegorical work in which the main character, the white man Clarence, makes it his business to meet the young king of an unnamed African country, a privilege he believes with great conviction that he has the right to simply because he’s white.

Toni Morrison described her first encounter with The Radiance of the King as shocking. The novel left her speechless. Here was a work that turned the cliché of a white man travelling in Africa on its head, and in doing so managed to rewrite the history of colonialism. Clarence is confronted with obstacles at every turn, and he’s blind to a fault to the realities around him, interpreting things as he thinks them not as they are. Clarence remains ignorant, persisting in his ignorance to the end. The novel cemented Laye’s reputation as a genius.

In his later work, Laye referred to the djeli’s as The Guardians of the Word, a free translation of the Mande phrase, Kouma Lafolo Kouma. In my own translation -Mandé is my mother tongue- it should be, those who know the origin of the word or who know the first word. The Mandé word djeli means blood, and nothing is as important in the Mandé culture as blood ties. This nomenclature highlights the importance of djeli’s and their work.

But what does the work of the djeli’s entail? The guardians of the word recorded the most important events and histories in many kingdoms in West Africa. For centuries, these history keepers passed on the traditions, the cultures and the daily activities of the societies in which they lived. They were not afraid to call a tyrannical ruler by name. This loyalty to the word is best illustrated in the work of the Ivorian writer Ahmadou Kouromah. This novelist explored the work of the djelis in his novels and even extended it. In his Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote, a satirical novel in which dictators from all over Africa are named, from Samuel K. Doe of Liberia to Étienne Eyadéma of Togo and Mobuto Sese Seko of Congo, a djeli narrates the life of a dictator while the man himself listens on:

President Koyaga, General, Dictator, today we will sing and celebrate your name and deeds. We will tell the truth, about your dictatorship, your parents and your collaborators. The whole truth about your dirty tricks, your bullshit, your lies, your many crimes and assassinations …

A djeli is never afraid. Telling the truth and being true to the kouma, to the word, is tied to his essence.

The djeli education was and it still is a lifelong one. The work is of such a great importance even today that a historical event that is told by a djeli in present day Gambia rarely differs from the one told by another djeli in many countries of West Africa. But until recently, the work and importance of these men and women were questioned by western historians, with the argument that the sources were not written ones and therefore unreliable. Even the existence of such eminent historical figures as Sundiata, whose life story is known even by children in West Africa, was considered a fabulous fantasy.

Sundiata Keita, according to the djelis, walked with a limp. The man was bowlegged, and as a child he was greedy and spoiled. The Sundiata who nevertheless rose up to found an empire that was the envy of the world. The Sundiata who compiled the famous constitution of the empire, Kurukan Fuga, one of the oldest constitutions in the world. In those lines proclaimed by the djelis on the rocky granite expanse, thus the name Kurukan Fuga, the rights of all the citizens of that great empire were guaranteed.

That we know Sundiata well is largely due to the efforts of a single man, his djeli, the famous Balafaseke. To illustrate the accuracy of these oral histories, Balafaseke tells us that he was captured by the great Soumangourou, the arch enemy of Sundiata. This ruler lavished Balafaseke with presents and honor and he tried to persuade him to be his djeli, but Balafaseke refused. Years later he returned to Sundiata because he had promised to tell his story to the next generation. Thanks to Balafaseke we know now that the name Sundiata reveals the essence of the man. The Mandé word ‘Sun’ literary means thief, and jata means ‘to take’ or the one who takes. This means that Sundiata became ruler by usurping power. Hierarchy in the Mandé culture is built on seniority. Sundiata was not the oldest of his father, which means he could not become king. So he became the one who took power, Sundiata. Balafaseke made sure that the word – the history of Sundiata and therefore of Mandé – was not polished to make of Sundiata a better king than he was to the next generations. Thanks to him Sundiata came to us a full and complex human being.

Out of this tradition and inspired by these stories, Ayi Kwei Armah wrote his book, The Eloquence of the Scribes (2006). This Ghanaian novelist, a Harvard graduate, is regarded as one of the greatest writers of the African continent and of the world. Many of his novels, like The Beautiful Ones are not yet Born and Two Thousands Seasons are already classics of the African literature. Armah’s international reputation would have grown to the level of Wole Soyinka, Chinua Archebe or Ngugi wa Thiong’o had he chosen to publish all his original work in the West. But he chose to publish his books in Africa, so that he could contribute to the promotion of book publishing and literacy in Africa.

Armah begins his book by heavily leaning on the work of another djeli, whose words were transcribed by the great Guinean historian Djibril Tamsin Niane in his book, Sundiata, An Epic of Old Mali, and who introduces himself with these words:

I am a djeli. It is I, Djeli Mamadou Kouyaté, son of Bintou Kouyaté and Djeli Kedian Kouyaté, master of the art of eloquence. Since time immemorial, the Kouyatés have been in the service of the Keita princes of Mali. We are vessels of speech, we are the repositories which harbor secrets many centuries old. The art of eloquence has no secrets for us. We are the memory of mankind.

Armah turned to the work of this djeli because he found similar djeli tradition within his own people, the Akan in present day Ghana and the Ivory Coast. This led him to place the djelis, these guardians of the word, within the context of the entire continent, including Egypt. Since his childhood, Armah had heard of how his people had migrated from old Egypt. He began to attach importance to these oral histories only after reading the work of the Senegalese scientist Cheikh Anta Diop. Diop claimed that the history of Egypt could not be told without placing squarely within the African continent, for Egypt was and has always been a part of Africa. Armah discovered similarities not only between the Akan language, his mother tongue, and the old Egyptian language but also in the traditions. Armah found that the task of the guardians of the word had been to keep the stories of the great migrations alive and to pass on to the next generations, so much so that millennia later the ways of his Akan people were in many ways like those of old Egypt, from where they once hailed.

It was the djelis, those guardians of the word, who took the cultures and traditions of Africa with them to the diaspora. Their care and mastery of the art of eloquence still resonate today in the works of rappers and spoken word artists of the diaspora, in their eloquence, their intonations, in the exchanges between the narrator (the lead singer), and his responder. It is seen in the melody of John Coltrane who, in his famous ode Alabama, succeeded in capturing the speech pattern of Dr. Martin Luther King in music, and in doing eulogized the death of four innocent children: ‘These children, unoffending, innocent and beautiful, were the victims of one of the most vicious and tragic crimes perpetuated against humanity.’

Stripped of their virtues and their humanity questioned, the Africans in the diaspora were left with no choice but to hold fiercely on to the word and to remain true to it. And true and protective they remained.

It was a djeli, Macandal, a man with one arm who, by telling stories to the enslaved Africans about their ancestors, unleashed the first successful slave revolt in history. Macandal inspired the Haitians people under the capable leadership of Toussaint L’Ouverture to wage a struggle that led to the founding of the first black republic in the Southern Hemisphere.

Being true to the word has been a decisive and recurring factor in every art and music form of the African diaspora. ‘Sth, I know that woman,’ so begins Toni Morrison’s novel Jazz. And we hear djeli Mamadou Kouyaté saying: ‘Listen, listen to my word.’

It begins and ends with the word, kouma.

This essay is the 3rd keynote of Alphabet Street, Black writers guild. It is the first keynote published in collaboration with De Tank, redactietank to enhance a Black/inclusive narrative in the Netherlands and Belgium. It was edited in Dutch by Neske Beks and published in a collaboration with the Dutch Review of Books (dnbg), Dipsaus and ZAM Magazine.