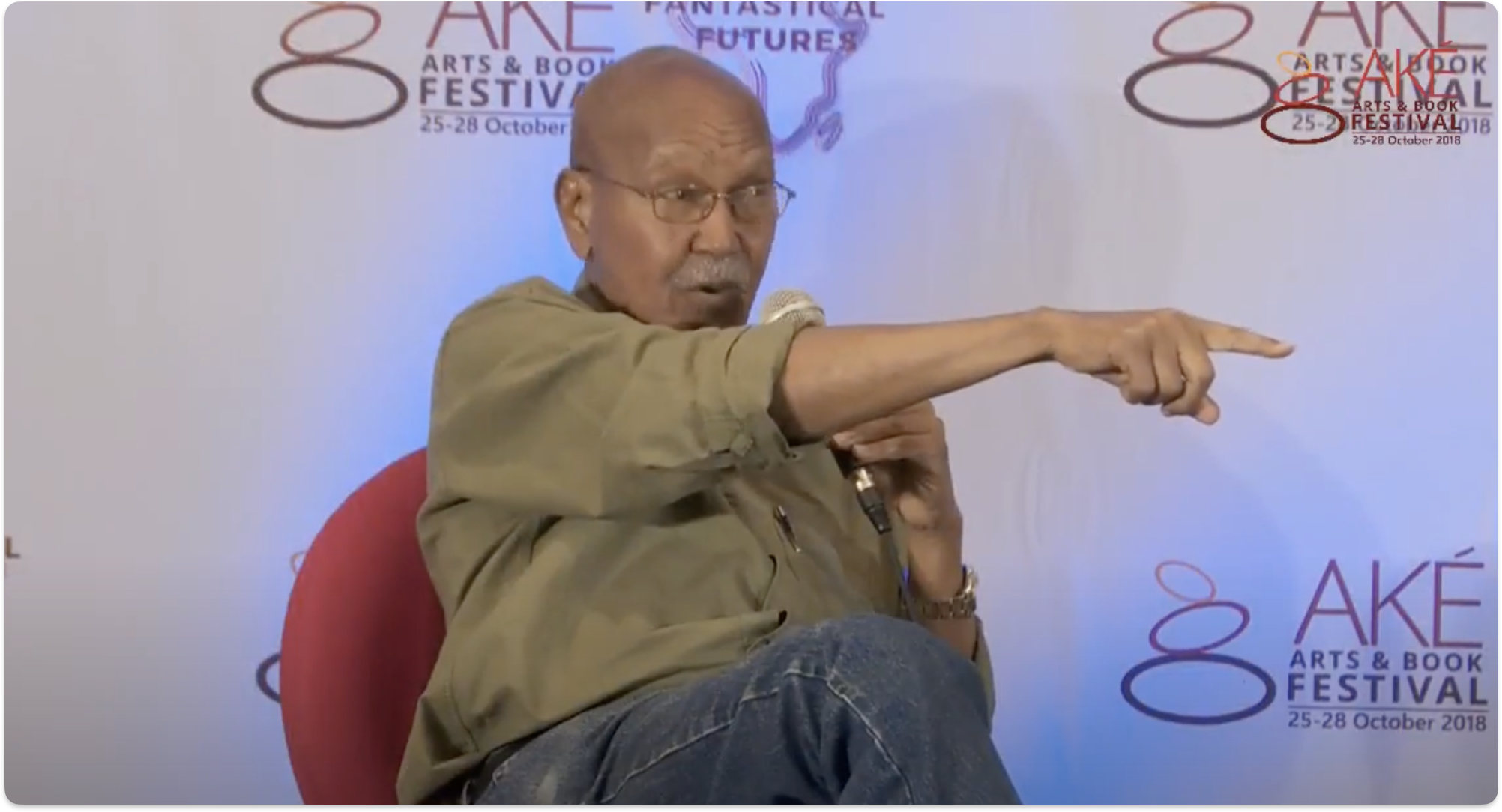

Vamba Sherif was impressed by the work of Nuruddin Farah from the first sentences he read in From a Crooked Rib. The girl Ebla in this debut novel reminded him of a girl in his youth who resisted vehemently to be married off. (Vamba was secretly in love with her).

I met Nuruddin Farah, the great Somali novelist, some years ago in the Netherlands after one of his novels was translated into Dutch and published by my publisher De Geus. I was invited to meet him in Utrecht where he was to give a reading and to attend the dinner my publisher and the people of that city had organized in his honor. Nuruddin Farah delighted us with captivating stories of his travels, especially the ones he made to former Soviet Republics such as Tajikistan and Kazakhstan, where he was received with great hospitality and served camel meat.

I had been reading Farah since my childhood, his every book an attempt to capture a piece of Somalia that he had carried as memory with him into exile. This is the curse and blessing of writers in exile, a curse in that they are forever bound to memory, and a blessing in that they are fortunate to express the sentiments of all exiles, to capture their longings and hopes in songs laced with melancholy.

I was impressed by Farah’s work the first time I read it. The novel happened to be his first From a Crooked Rib (Heinemann African Writers Series, 1970). I read this remarkable book during my childhood in Kolahun, my birthplace in Liberia, thanks to one of my brothers who loved literature and who bought every copy of the famous Heinemann African Writers Series. Our father, the imam of the mosque in my city, had decided to send several of his many children to a government school where lessons were taught in English. This was in contrast to the Islamic school, the Majlis, which he headed as scholar and which comprised dozens of students. These students would gather around a burning hearth in front of our compound in the early hours of dawn. They would recite in chanting and beautiful voices at the top of their lungs verses or Suras from the Quran and its exegesis which were written on wooden tablets. The students were instructed by young scholars who had been taught by my father and who had taken up from him the responsibility of teaching the children. Despite this venerable tradition which had made our house, the Sherif or Haidarah House, great through the centuries since the arrival of Islam in West Africa, my father decided, perhaps as an experiment, to deviate from this tradition and to send a few of his children to school, one of whom turned out to be a great reader of novels written by Africans.

But by the time I was old enough to read From a Crooked Rib by Nuruddin Farah, my father was long dead. The books belonging to my brother were kept in a wooden box in my father’s room, on the right of the door that led to a room that contained hundreds if not thousands of manuscripts in Arabic that no one in the family was allowed to touch after my father’s death. Without asking my brother’s permission, a trait that would land me more than once in trouble, I searched the wooden box with his books and began to read them one by one. This is how I discovered not only Farah’s novel but other great novels, like Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, Weep Not Child by Ngugi wa Thiong’o, The Beautyful Ones are Not Yet Born by Ayi Kwei Armah, A Woman in Her Prime by Bediako Asare and the novels and stories of the great Cyprian Ekwensi, not to mention the widely read and one of the most famous novels in Africa, The African Child or The Black Child by Camara Laye.

What I found remarkable about Nuruddin Farah’s novel was that he had decided to go the other way. From a Crooked Rib was not a novel that addressed the lingering effects of colonialism on Africans, like the works of Achebe, wa Thiong’o, Soyinka and others had attempted to do. Farah had chosen to address the place of women in Somali society, which was, like my community, Islamic. The protagonist, a woman called Ebla immediately struck a nerve with me. And not without a reason. For while I was reading the novel, a drama was unfolding before me that ran parallel to Ebla’s story. A girl whose sister was married to one of my brothers and who was a few years older than me was being forced to wed a man who was older than her father. In fact this man was older than my dead father. The girl was a great beauty and I was secretly in love with her. The girl resisted this arrangement vehemently. In the end, just like Ebla in the novel, she escaped to the capital city.

It was proof of the enduring relevance of literature that a novel written by a Somali thousands of miles away from me and who in his time had captured in uncanny ways the event that was unfolding before me in a different country and in a different time, in my time.

That Nuruddin Farah, a man, wrote the novel from the perspective of a woman was another aspect that I found unique. But much more important than this was the protagonist Ebla herself. Ebla’s desire to determine her own future despite the judging and convicting eyes of society, reminded me of some women of my world, including my mother. I admired her courage and bravery. The novel was moreover sprinkled with erotic sentences which delighted me even as they surprised me, especially because I was growing up in a society where the erotic was only alluded to and not talked or written about.

In many of Farah’s novels, the recurring theme is his preoccupation with home, in this case Somalia, and the troubles that have plagued the country over the years. That’s why his characters, many of them exiles, keep returning to Somalia in search of answers. In the meantime, they’ve become strangers in exile, and the answers they find on returning home are most often heartbreaking. Memory, once a source of solace, an anchor during exile, clashes with reality. Homecoming becomes a source of contradictions. Farah shows us this over and over again like few writers of his generation. This makes him one of the greatest chroniclers of memory. He keeps showing us with every book the journey of the mind if not the body of the exile between the world left behind and the world presently inhabited, swinging like a pendulum between the two, belonging to neither.