A new abolition movement is gaining momentum in the Igbo region of Nigeria, fuelled by social media.The movement fights old home brew systems of slavery.

There are global efforts to fight modern slavery, but a few traditional systems still hold strong in west Africa. These include Osu, Ohu and Trokosi. The Conversation Africa’s Godfred Akoto Boafo spoke to Michael Odijie who has researched one of the systems – Osu – and what can be done to finally put a stop to it.

What is Osu?

Osu is a traditional practice in the Igbo region, in south-eastern Nigeria. In the past, Osu involved dedicating individuals to local deities, “transforming” them into slaves of the gods. Though such dedications no longer take place, the descendants of past Osu suffer from discrimination and social exclusion.

Historically, there were several ways a person could become an Osu. Some were purchased as slaves and then dedicated to local gods, either to atone for a crime committed by the purchaser or to seek assistance from the deity. An individual might attain the status of an Osu through birth if one of their parents was an Osu or through voluntarily seeking asylum, thus assuming the Osu status. For example, during the transatlantic slave trade, many chose this path: they would run to a shrine and dedicate themselves, to avoid being sold. Once dedicated as an Osu, they were generally ostracised from Igbo communities, yet simultaneously regarded with fear, seen as the slave of a deity.

Another common way to become an Osu was through marriage to an Osu, leading to persistent marriage discrimination even today.

The spread of Christianity, which occurred rapidly among the Igbos in the 20th century, discouraged the practice of worshipping local deities. The historical practice of Osu has ended.

However, a new form of discrimination has taken its place, targeting the descendants of those historically identified as Osu.

One of the most significant forms of modern discrimination occurs in the realm of marriage. Freeborn individuals, who have no Osu lineage, are customarily prohibited from marrying someone of Osu lineage. Should they do so, both they and their offspring permanently become Osu, facing the same discrimination. This discrimination has a profound impact on the social and emotional lives of many Igbos of Osu lineage, particularly those of marriageable age. It can be challenging for them to find a spouse.

Another form of discrimination nowadays is social exclusion. In Igbo villages, Osu live in segregated quarters and are barred from social interactions with freeborn community members. They face barriers to accessing certain public amenities, attending community events and participating in communal decision-making processes.

Their descendants are also restricted from holding specific influential positions in the Igbo village power structure, such as the Okpara (the oldest man in the village) and the Onyishi.

How prevalent is Osu and where is it practised?

G. Ugo Nwokeji is an Igbo cultural historian who studied slavery in the Igbo region. He estimated that the Osu represented 5%-10% of the Igbo population. With an ethnic population of about 30 million Igbos in Nigeria, this suggests that between 1.5 and 3 million Igbos suffer from this discrimination.

The vast majority of Osu are found in Imo State, which has about 5.2 million people. But they are in every other Igbo-dominated state as well: Enugu, Anambra, Ebonyi and Abia.

Why has it been a challenge for governments to end the Osu practice?

In 1956, Nnamdi Azikiwe, then the premier of Eastern Nigeria and later the first president of Nigeria, spearheaded the passage of a law aimed at abolishing Osu and its social disadvantages.

But the practice continued. No arrests were recorded. Osu is deeply rooted in tradition, making a purely legal approach insufficient.

One reason why eliminating discrimination has been difficult is that identifying an Osu is relatively straightforward for Igbos. They often reside in their own distinct quarters. Therefore, simply mentioning one’s village or family name can reveal one’s Osu status. This situation is a result of a combination of Igbo culture and colonial policy from the 1920s. During this period, individuals of slave origin began to assert themselves, and the British colonial response was to segregate them.

What other approaches should be tried?

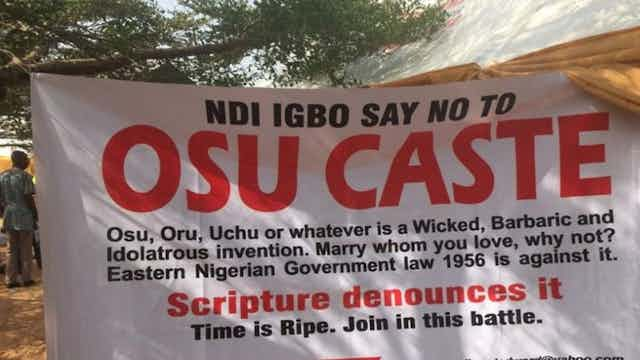

A new abolition movement is gaining momentum in the Igbo region of Nigeria, fuelled by social media. This has enabled widespread awareness and advocacy, creating a more robust and inclusive dialogue about the Osu system.

One of the leading groups in this new movement is the Initiative For the Eradication of Traditional and Cultural Stigmatisation in Our Society, a network of campaigners led by Ogechukwu Stella Maduagwu.

Recognising that the Osu system is often viewed as having spiritual significance, the initiative places greater emphasis on the advice of cultural custodians, including traditional rulers. Consequently, it has developed a “model of abolition” that involves consultation with cultural figures, such as chief priests representing the deities, in Igbo villages. Using this model, the organisation successfully conducted an abolition ceremony in the Nsukka region of Enugu State.

Another leading campaigner is Nwaocha Ogechukwu, a scholar and researcher specialising in religious and cultural discrimination. He has established a platform named Marriage Without Borders to assist young people who face marriage discrimination due to being labelled as Osu. In collaboration with religious leaders, he provides counselling and support to those suffering from the adverse effects of this system.

A challenge for the emerging movement is its localised approach. Without a strategy that encompasses the entire Igbo region, campaigners are unable to collaborate effectively or engage in a unified, sustainable effort. This issue arises from the diverse genealogies of the Osu and the lack of a single traditional Igbo authority.

As a result, the movement has found it difficult to gain widespread traction. It continues to have a village-level focus.

We recommend that the movement align itself with broader human rights campaigns within Nigeria, across Africa and internationally. The Osu system bears resemblances to Ghana’s Trokosi system. The campaign to abolish Trokosi achieved notable success because its message resonated on a national level, garnering support from international activists.![]()

Michael E Odijie, Research associate, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.