How the ‘tobacco system’ keeps farmers in poverty

During a check on multinationals who pay tax in various locations, we come across a Malawian tobacco company, Alliance One Tobacco Malawi (AOTM). It belongs to an American multinational corporate chain and boasts of being one of the chain’s top revenue providers. The company makes its profits from raw tobacco exported from the small African country, whose population of 20 million is not much bigger than that of the Netherlands. Yet, it pays practically no tax in Malawi itself, while it makes extraordinarily high payments abroad.

Malawi is the fourth poorest country in the world.

AOTM is the second-largest tobacco leaf buyer in Malawi, accounting for about 40 percent of the country’s tobacco market share. According to trade data, AOTM exported 319 million US$ worth of raw tobacco between 2020 and 2022. However, a document from a source within the Malawi Revenue Authority, the MRA, confirms that Alliance One paid no income tax in Malawi itself at all in 2020, and in 2021, it paid only US$ 41,000 of corporate income tax there. In the same period, the company made payments abroad of close to US$ 1,4 million in 2020 and over US$ 2,8 million up to October 2021.

No comment

Puzzlingly, the MRA, the institution charged with chasing money for the country’s small state budget, doesn't appear to be interested in discussing the matter. We alert the institution in numerous communications and requests for comment, but no meaningful responses are received. Though privacy rules forbid tax authorities in many countries, including Malawi, from talking about individual tax clients, -and MRA spokespersons tell us twice that they will not comment on Alliance One for this reason-, the MRA also keeps mum on general questions about the tobacco sector or its policies vis à vis multinationals (see box: 'The Malawi Revenue Authority will not respond'.)

The Malawi Revenue Authority will not respond

The Malawi Revenue Authority was first contacted for comment by email in November 2023, but no response was received. When contacted by phone, a spokesperson requested new emailed questions, which were sent. MRA spokesman Henry Mchazime then called Josephine Chinele saying that it “would take them a bit of time to respond” because it “involved several departments” and it was “on sensitive issues.” He announced that he would organise a meeting where Chinele could “speak directly with some directors.”

After several days, Mchazime invited Chinele to a meeting to be held that week. Chinele explained that she was attending a course out of town. She offered to come for the meeting after working hours or online, but Mchazime said that that was not possible. Two days later, Mchazime called Chinele again, this time at 5 AM, saying that she could “just walk into the office” and meet a colleague who would give her “partly off the record” information. Chinele reiterated that she could not meet that week and explained that on-the-record answers were needed.

After another reminder to respond, Mchazime then sent Chinele angry texts, accusing her of “not availing” herself. When Chinele explained that if the MRA did not send responses, the story would be published without them, Mchazime then called Chinele’s senior editor at the Platform for Investigative Journalism in Malawi, Gregory Gondwe. He complained to Gondwe that Chinele “wasn’t cooperative” and invited Gondwe to come to a meeting with “the bosses.” However, he never offered a day or time. He then stopped communicating.

When, still several days later, Chinele messaged Mchazime's supervisor, Wilma Chalulu (to whom Mchazime had referred all further contact ), Chalulu responded that she “thought we would be meeting” but if that wasn’t to happen, “MRA cannot answer (these) questions because they contained a taxpayer’s confidential information.”

In a last effort, the ZAM office sent the questions to Mchazime and Chalulu. Mchazime then wrote to ZAM reiterating Chalulu’s response that the MRA “does not comment on taxpayers’ status.” ZAM followed up with two other emails, asking for responses to several questions about multinationals’ tax generally, without referring to Alliance One, but received no responses to these either.

“Our (government) duty-bearers are aware that these companies are not paying enough,” says Michael Msukwa, tobacco farmer and chairman of thirty community farming groups, called clubs, in Malawi’s northern region. He suspects that the reason for the authorities’ lack of action in this respect is that “someone may be benefiting from these deals at the expense of our sweat.”

“Our duty-bearers are aware that these companies don’t pay enough”

Our investigation did not find evidence to support Msukwa’s suspicion, but it is a fact that farmers are kept in extreme poverty under present tobacco deals in Malawi. In Msukwa’s region, farmers who grow the “green gold” (as tobacco is called in Malawi) work long hours for a yearly net income of little more than one or two thousand US dollars. In Msukwa’s case, it was just US$ 1,190 for the whole year of 2022.

Ironically, the reigning tobacco system, called IPS (Integrated Production System), which governs farming contracts between tobacco growers and buyers, is advertised by the companies as a guarantee to “blue chip” customers in the cigarette industry that tobacco is farmed in compliance with quality and environmental standards, without any child labour. But because of the extremely low income, many farming families are still forced to use their children to help. Child labour and unsafe work amid pesticides are therefore still widespread.

If tax was collected from tobacco buyers such as Alliance One, Malawi’s budget could be increased to help the 75% of Malawians who depend on farming, says social accountability expert Wales Chigwenembe. “Tax non-compliance (now) cripples our government’s potential to invest in sectors such as agriculture.” Farmers like Msukwa, who desperately need to be supplied with certified seed, approved fertilisers, personal protective equipment, and crop protection agents, now depend on loans and material inputs from tobacco buyers like Alliance One. These, Msukwa and others say, bind them into unfavourable contracts.

Exploitative contracts

Msukwa says that in the 2022-2023 farming year, on a loan of the Malawi Kwacha equivalent of US$ 2,980, he repaid US$ 5,950 after the harvest season. It was this arrangement which, he says, only left him US$ 1,190 for the year. Msukwa would much rather have government support for his inputs, he says, but only the companies provide these.

Malawi’s Ministry of Agriculture stated in response to questions that it does provide loans and inputs to “hundreds of farmers”, but that is a miniscule portion of Malawi’s 350,000 tobacco growers.

“We keep the farmer at the heart of everything we do.”

Alliance One, for its part, said that “farmers can accept or decline to take its loans” and that its contracts are “fully transparent” and “provided in English and two other local languages for the farmers’ understanding.” The company also denies that its contract system is exploitative to the farmers, stating: “We keep the farmer at the heart of everything we do" (see box: Alliance One Tobacco Malawi Comments).

We try to find AOTM's financial statements for a look at its profits and tax payments, but the Registrar of Companies in Blantyre cannot help us with that. Repeatedly forgetting about our paid-for request, then finally, after numerous phone calls, saying he cannot find it, a staff member called Mr Tembo refers us to AOTM itself, where one of the directors tells us that he "cannot divulge such confidential information" to a journalist he doesn’t know.

“Failing to provide financial statements is a red flag.”

Later, Françoise Malila, AOTM’s Corporate Affairs Manager, states in response to questions that, as a subsidiary of a US multinational, AOTM is not obliged to publish their annual reports, adding that “our [AOTM’s] contributions are consolidated and publicly reported quarterly on a global scale.” This is of little help, since the financial statements she speaks of are those of the US-based parent company Pyxus, which don’t specify AOTM profits and tax payments.

Alliance One Tobacco Malawi comments

A new last-minute response received from Alliance One Tobacco Malawi states that “tobacco pricing is based on regulated Government Minimum Prices and demand and supply dynamics” and that the process is “managed by the Tobacco Commission and the Ministry of Agriculture.” The response further explains that farmers who contract with AOTM can “access loans from commercial banks in Malawi”, whereby “AOTM guarantees each loans’ performance with the banks, (which helps to) secure it at an interest rate lower than the market average,” adding that farmer contracts, “which include input costs and the loan value,” are vetted with the Tobacco Commission.

Regarding working conditions, AOTM says it “provides training on basic human rights and a decent work environment and prohibits the use of child or forced labour.” On the issue of its financial statements, it reiterates that “as a subsidiary of a publicly traded, US Company, AOTM does not publicly report entity financials, nor are we required to do so; however, our contributions are consolidated and publicly reported quarterly on a global scale.”

“Failing to provide [the company’s] financial reports to Malawian citizens is a red flag,” Wales Chigwenembe comments. “Multinational companies usually use their global [presence] to dodge tax, among other financial crimes. They’re operating in Malawi, profiting from the country’s important crop. Why should they hide their reports through international parent companies?”

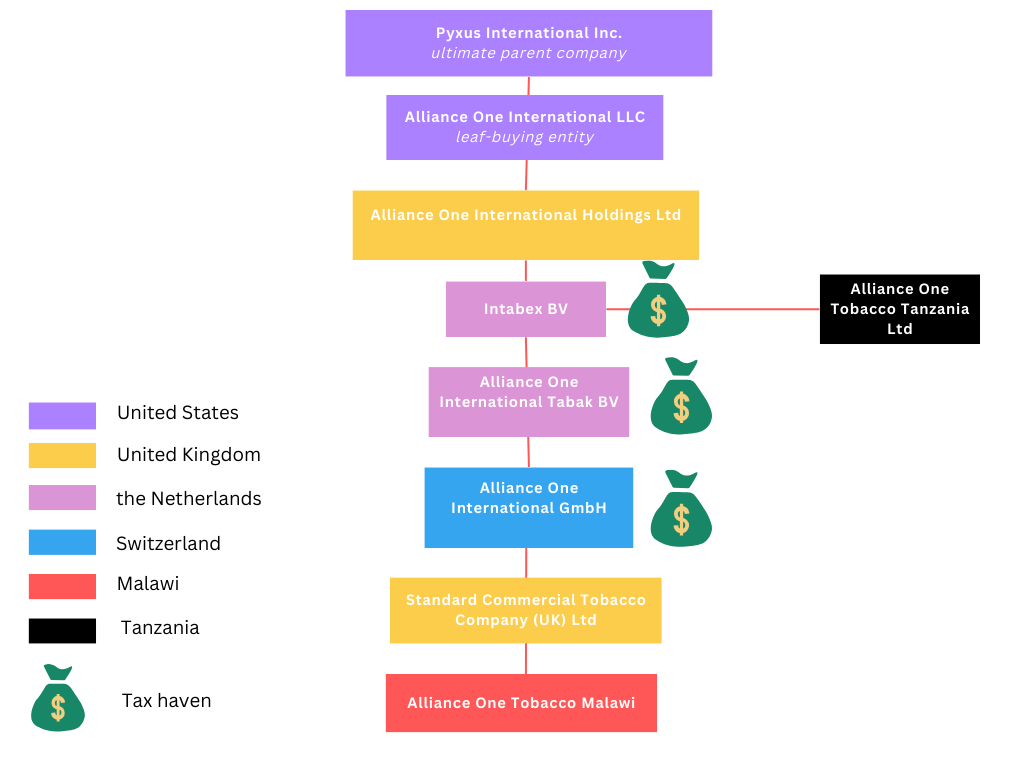

The tax document obtained from our source in the MRA shows that, while the company paid just over US$ 41,000 corporate income tax in Malawi between 2020 and October 2021, it made payments of around US$ 1,4 million and US$ 2,8 million abroad in the same period. These payments followed a common pattern among multinationals, whereby taxable income is turned into “expenses” that end up with a sister company in the same corporate chain, allowing the company to pay less tax. (see box below: How transfer payments work). It's uncertain where the payments went. There are three subsidiaries located in tax havens – Switzerland and the Netherlands – between AOTM and its ultimate parent, Pyxus International in the US.

Rapped on the knuckles

A 2021 court case from a sister company of AOTM, Alliance One Tobacco Tanzania Ltd (AOTT), shows how this company avoided to pay tax in Tanzania, and was rapped over the knuckles for it by an alert tax authority. Auditing AOTT’s financial statements over several singular years between 2003 and 2011, the Tanzanian Revenue Service concluded that a listed cost for “sales” was income disguised as a cost. Despite AOTT’s defense that “the disallowed costs were deductible as they were wholly and exclusively incurred in the production of the income”, the court ruled that the company failed to provide evidence, such as invoices, to substantiate this. Their objection was therefore rejected, the appeal case dismissed, and AOTT was ordered to pay the appeal’s costs as well as its income tax bill.

“I think that's a pattern that's replicated everywhere in the African countries that produce for these [multinational] companies,” says Marty Otañez, an anthropology professor at the University of Colorado Denver, who spent years researching the tobacco sector in Malawi. “It doesn't surprise me. The only surprise is that this kind of knowledge happens to leak in these [court case] details.”

Labour abuses are endemic in the tobacco system

In an ongoing class action lawsuit since 2019 in the UK, Malawian farmers represented by law firm Leigh Day have accused cigarette companies British American Tobacco (BAT) and Imperial Tobacco of facilitating “unlawful and dangerous [working] conditions” in Malawi. The farmers claim to work from 6 AM to midnight every day of the week, live on too little food, and still get paid nothing at the end of the growing season. According to Leigh Day, about 70% of the farmers they represent work on AOTM farms, since the company supplies both BAT and Imperial Tobacco. Martyn Day, one of the firm’s lawyers engaged with the case, says that the labour abuses “are endemic to Malawi due to the way the tobacco system is set up.”

The structure of the multinational. Image by Zuza Nazaruk

Ducking and diving

When asked why the state of Malawi still maintains this “tobacco system”, various authorities in the country dodge our questions. The Ministry of Labour, which is supposed to monitor and ensure good working conditions on Malawi’s farms, doesn’t respond at all. Neither does the Ministry of Finance to questions about the possible flight of tax income from Malawi. The Tobacco Commission, which oversees the sector, says through its spokesperson that it is “currently looking into various issues related to (tobacco) contracts” and that it wants to “ensure that contracts benefit the industry in Malawi.” However, after further questions regarding tobacco pricing, price fixing – a continuous accusation made by farmers against the tobacco companies (1) – and the reasons why the country, to date, has not made any progress regarding processing of raw materials such as tobacco (which would yield much more trade income) the spokesperson stops responding.

For its part, the Ministry of Agriculture, in addition to its statement about supporting “hundreds” of farmers, only sends us a copy of a recently passed new Tobacco Bill, saying that “it addresses the issues raised as well as more.” Perusing the bill, however, we can’t find any commitment by the state to improve the sector. In contrast, it appears to place the responsibility for issues such as child labour, reforestation, diversification away from tobacco, safety, and working hours for farm employees squarely on the shoulders of the growers. “A grower shall at the beginning of the season furnish the (tobacco) commission with undertakings how they dealt with (such) issues,” it says, upon “penalty of deregistration” and other sanctions.

The new law also has “the farmer at heart.”

The bill also does not contain information on effective ways or means for tobacco farmers to access state loans, assistance with diversification, or otherwise escape from the grip of the tobacco companies. It only stipulates that the Tobacco Commission will “impose minimum terms and conditions for the contracts” with tobacco buyers; but what these will be, the commission had not explained in time for our deadline. Echoing the statement previously made by the AOTM spokesperson, the Ministry of Agriculture ends the message accompanying the text of the new law by saying that it “has the farmer at heart.”

How transfer payments work

Bob Michel, comparative policy and legal analyst at the Tax Justice Network, and Vincent Kiezebrink, researcher at the SOMO Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations in the Netherlands, immediately point out the high number of so-called Withholding Tax (WHT) payments in the tax document we obtained. “This is a levy that you pay on amounts that are transferred to foreign entities,” explains Kiezebrink, adding that such amounts are often called dividends, royalties, interest payments, or management or technical fees. According to the tax document on AOTM, the company made substantial payments abroad in 2020 and 2021 for interest on loan, management, or technical fees. “These payment volumes mean that the company (AOTM) has profit, and a lot of this profit is turned into ‘expenses’ that go abroad,” says Bob Michel.

How companies do this, for example, is by getting a loan from another company within the corporate group, which is located in a country with lower taxes. Then it pays interest on the loan, which means paying sums of money to the sister company in the tax haven. Since interest payments are a cost, this reduces taxable profits in the original country. For the loan-giving company abroad, the interest is profit, but, since it is in a tax haven, it pays much less tax on that profit than if the money would have stayed in the country where it was generated. The WHT levy that is paid in Malawi to facilitate these payments is only a fraction of the amount the company would otherwise have paid in corporate income tax.

(1) See on cartels that fix prices:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03056244.2018.1431213?needAccess=true and

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305379990_Farm-Level_Economics_of_Tobacco_Production_in_Malawi “These poor prices are attributed to a globalised cartel of international tobacco companies and government elites which, fixing the prices at auction, exploit local growers and impoverish smallholder households.” (Smith and Lee, 2018).

This collaborative cross-border investigation is part of the Investigate East and Central Africa programme under the supervision of The Civil Forum of Asset Recovery (CiFAR).

Other articles based on this investigation are also published by The Continent and by the Platform for Investigative Journalism in Malawi.